The Rise, Then The Fall of GOP’s ‘National Rabbi’

?Brooklyn Bundler?: A court convicts Rabbi Milton Balkany. Image by STAN HONDA

Updated, November 17, 2010, 5 p.m.

The storied career of an indomitable ultra-Orthodox political fixer appears to have entered its final phase with the conviction of Rabbi Milton Balkany, known to the press as the “Brooklyn Bundler.”

?Brooklyn Bundler?: A court convicts Rabbi Milton Balkany. Image by STAN HONDA

Balkany was found guilty November 10 of attempting to extort $4 million from Steven A. Cohen, a hedge fund manager. The rabbi is now home on $1 million bail, allowed only to see his doctor and to attend synagogue once a week as he awaits sentencing.

Balkany, whose only official job is as dean of a Boro Park girls yeshiva, has been known for decades as a major donor to conservative politicians, capable of bringing home significant government cash to causes dear to the Orthodox community. He has also escaped conviction in a number of previous financial scandals.

“There has never been [another] Balkany,” New York Democratic consultant Hank Sheinkopf said. “No one has ever wielded that kind of influence, in recent memory, over the period of time that he did.”

Balkany rose to prominence in the late 1980s, when he was among those to connect the ultra-Orthodox community to politicians as a source of political donations. He was dubbed the “Brooklyn Bundler” in 1990 by the now defunct Common Cause magazine for his prowess in bundling together political contributions from numerous donors to favored politicians for maximum impact. Known as a major giver with ties to deep ultra-Orthodox pockets, Balkany was particularly influential during the mayoralty of Rudolph Giuliani, who led New York City from 1994 to 2001.

“He was a power player; he had access to City Hall; he had a lot of friends,” Sheinkopf said. But he added, “Those years are gone a long time.”

Balkany’s ultimate fall began last May, when he was indicted on charges that he had threatened to facilitate the delivery to law enforcement authorities information about alleged insider trading at SAC Capital Advisors, the hedge fund run by Cohen, unless Cohen paid him. Balkany said that he was in touch with an inmate at an upstate New York federal prison who would talk to federal investigators unless Cohen paid $2 million to Balkany’s girls yeshiva and $2 million to a second yeshiva. According to the indictment, Balkany told lawyers for Cohen’s firm that cash to the second yeshiva would eventually be repaid.

In surreptitiously recorded conversations between Balkany and SAC Capital representatives that were played during the trial, Balkany boasted of his political connections. “Every six weeks, a different senator from Washington comes to my house for lunch or dinner,” he said on the tapes, citing such present and past senators as Orrin Hatch, Joseph Lieberman, Arlen Specter, Ted Kennedy and Max Baucus.

There’s little cause to assume that Balkany is exaggerating. The catalog of boldface political players gives a hint as to the level of Balkany’s access, carefully cultivated through years of donations.

His power, Sheinkopf said, came from “his ability to raise money, which gave him access, which gave him the ability to deliver things for his community that some thought were not possible to do. He was a great bundler. Money matters in politics; he was able to raise it.”

In tandem with his financial donations, Balkany worked to construct an image of himself as a rabbi to the powerful. “The perception, and in many ways the reality, was that Rabbi Balkany wanted to be known… as the rabbi who Republican national leaders felt very comfortable inviting to deliver invocations, and to be seen as the national rabbi,” said Ezra Friedlander, founder and CEO of the Friedlander Group, a lobbying firm specializing in representing not-for-profits from the Orthodox community.

Balkany is tied by marriage to the Rubashkin clan, which ran the kosher meatpacking firm Agriprocessors until it was hit with criminal charges in 2008.

Despite his conviction, Balkany, a mainstay of his community, has not been abandoned by his friends.[

“I am very saddened by these latest developments,” Friedlander said. Balkany, he explained, “has done so much for our community in the realm of education and advocacy and just simple chesed,” using the Hebrew word for “compassion.”

“He was a great human being and a great person to deal with,” said Isaac Abraham, a former New York City Council candidate from the Satmar community. “He did a lot for this community and leaves a big vacuum.”

Asked whether the conviction changed his perception of Balkany, Abraham said, “I judge him by the 25, 30 years that I’ve known him, not by one issue.”

But Balkany has been embroiled in a series of funding scandals over the past decade and has escaped serious consequences in all but the latest incident.

A January 2000 Daily News report found that Balkany was charging Jewish families for his help in accessing child day care vouchers for low-income families. The report raised suspicions that applications submitted via Balkany received special consideration from the city as families elsewhere got put on long waiting lists. More than half the vouchers went to four heavily Orthodox Brooklyn neighborhoods, and the number going to the Brooklyn ZIP code in Boro Park where Balkany’s school and several others he helped were located was about five times the number of vouchers distributed in Manhattan and the Bronx combined. Balkany was never charged in this case.

In 2003, he was the subject of a federal indictment charging him with misuse of $700,000 granted to his yeshiva by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The grant was intended to be used to pay the mortgage on a new building for disabled preschoolers. Instead, the complaint alleged, Balkany used the money for other expenses, including $78,000 that he simply signed over to himself.

At the time the grant was made, the secretary of HUD was Andrew Cuomo, now governor-elect of New York State.

Prosecutors dropped the 2003 charges after Balkany cut a deal, admitting he was wrong and agreeing to travel restrictions and to pay restitution to HUD.

Now, it appears that Balkany’s attempts to extort Cohen may have ended his career for good. “Oftentimes people who once were powerful and are no longer powerful find themselves desperate, and that may be what happened here,” Sheinkopf said. “It’s hard to give up power, and it’s hard to be told you’re not powerful anymore.”

People who knew Balkany say that there is no one else operating in the Orthodox community today who is comparable to him. And, even leaving aside the criminality, some say there shouldn’t be. Friedlander said that organizations in the Orthodox community that need lobbyists should use professionals like him, not freelancers like Balkany.

“They should turn to a professional government relations company that lobbies, one that does it in full compliance with the law, in an ethical, transparent way,” Friedlander said. “Turning to a person on an ad hoc basis — ‘Do me a favor. Do you know someone there that can help out?’ — that’s not a very effective method of advocating for your cause.”

Contact Josh Nathan-Kazis at [email protected] or on Twitter @joshnathankazis

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

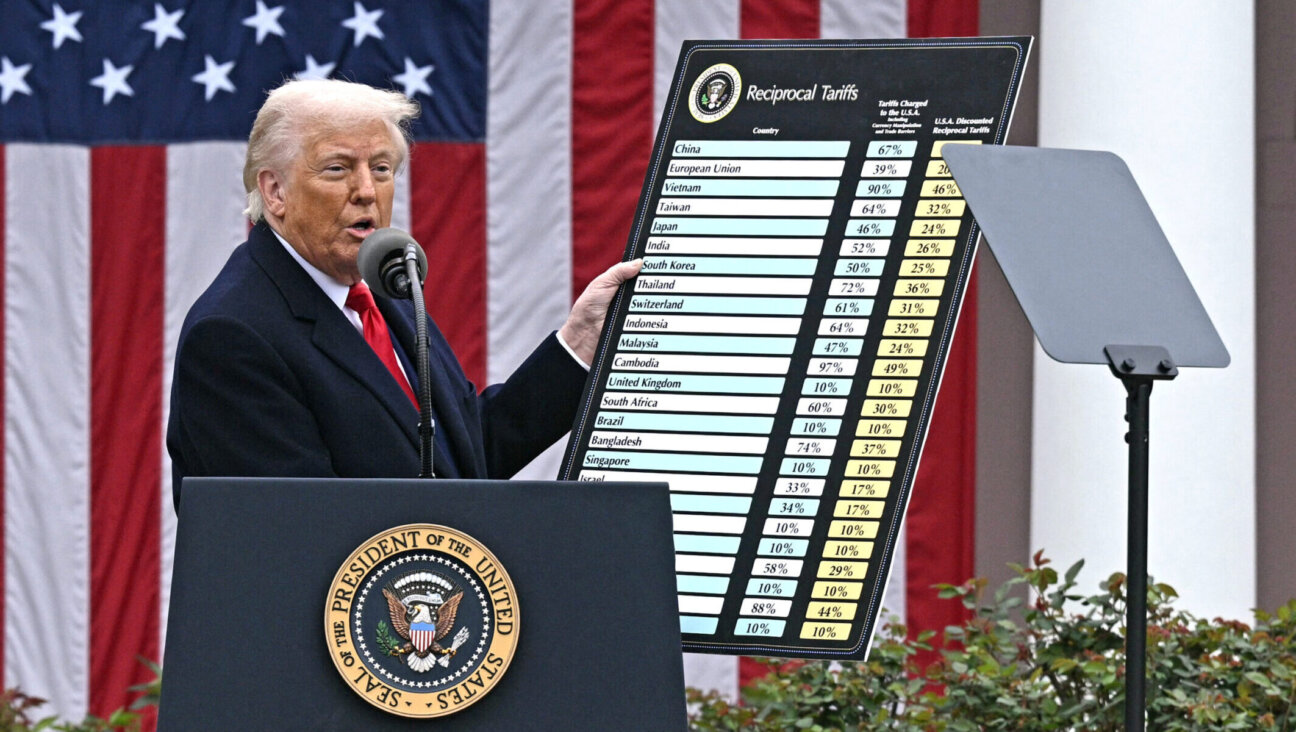

Fast Forward Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ includes 17% tariffs on Israeli imports, even as Israel cancels tariffs on US goods

-

Fast Forward Hillel CEO says he shares ‘concerns’ over campus deportations, calls for due process

-

Fast Forward Jewish Princeton student accused of assault at protest last year is found not guilty

-

News ‘Qatargate’ and the web of huge scandals rocking Israel, explained

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.