Teaching Poetry No Longer

The Poetry Lesson

By Andrei Codrescu

Princeton University Press, 128 pages, $19.95.

Creative writing programs over the past half-century have endorsed the maxim “Write what you know,” so why don’t we have more novels about creative writing programs? Departmental meetings, thesis advisories, workshop tensions, suicidal poets, deferred student loans — the material is ripe for the picking. As Andrei Codrescu says to his “Introduction to Poetry Writing” class in “The Poetry Lesson,” his new book about his tenure teaching writing at Louisiana State University:

Minutes ago your teachers were students themselves, then student-teachers, then assistant professors, then tenured professors, and the whole process was uninterrupted by anything more than a summer vacation in Europe. We are teaching in an institution run by institutionalized people who have invested all their time into the institution! The lunatics run the asylum!

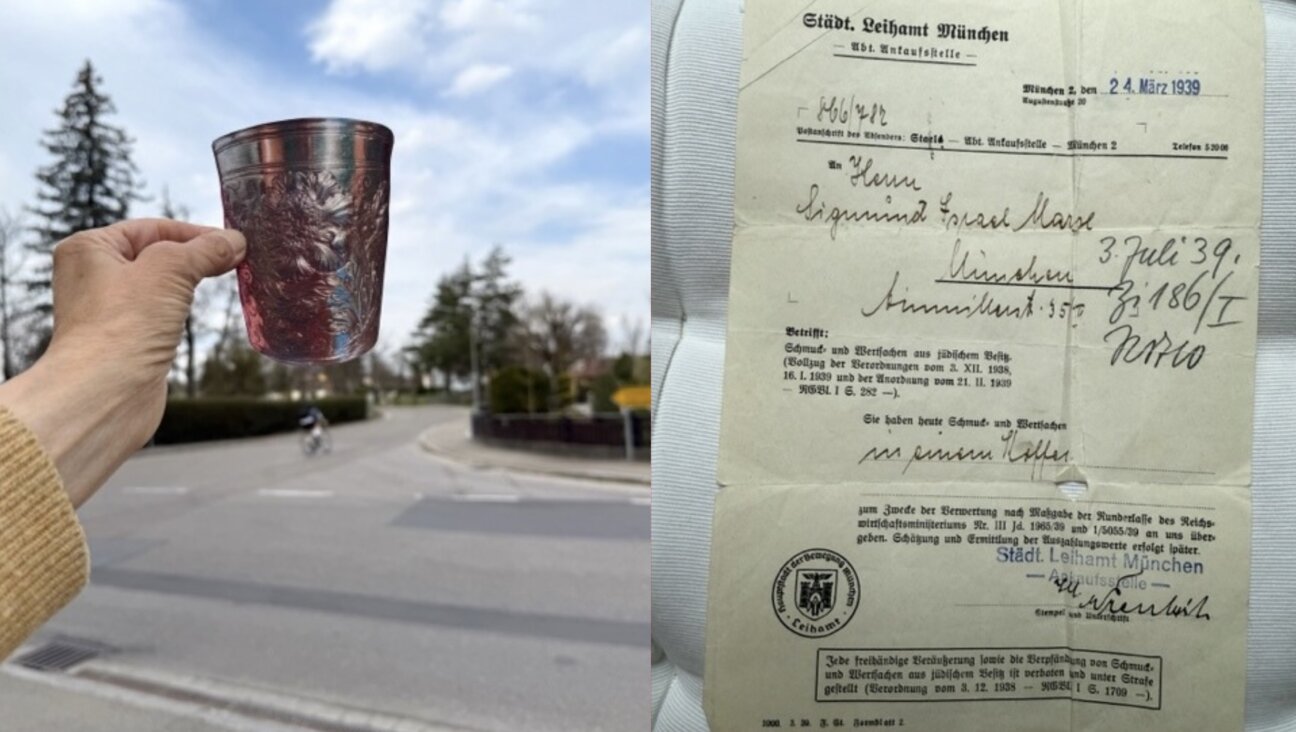

Chapters on Verse: Codrescu writes into retirement. Image by MARION ETTLINGER

Peculiarly, most writers would rather use as their subject that summer vacation in Europe than the hours, days, years, decades in the university. Codrescu’s not-novel, not-poem, not-memoir (though yes something-nonfiction), “The Poetry Lesson” has thus effortlessly landed at the forefront of the “Books About Writing Class” genre, an accomplishment regardless of the lack of competition.

Of course, Codrescu could write such a book: His identity is not threatened by the venture. He was born in Sibiu, Romania; fled the communist regime; sojourned in Italy; immigrated to the United States at 20 years old and proceeded to get drunk with great poets in great American cities before settling for a notably diverse literary career in Louisiana. A poet, novelist, essayist, screenwriter, commentator on NPR, editor of the literary journal Exquisite Corpse, distinguished professor of English and lifelong partisan of the avant-garde, he has averaged roughly two books a year since 1970, and if he’s worn himself a bit thin, it’s okay, because he can always rely on that Eastern European otherness, his good-naturedly transgressive charm.

“The Poetry Lesson” begins at the start of a first “Intro to Poetry Writing” session and ends three hours later, with the class’s dismissal. Codrescu is set to retire at the end of the semester, so this is his final first class, his last fresh batch of pupils whose faces momentarily merge into the “famous Time magazine cover of the twenty-first century human”; who arouse in him pity (alternately for himself and for them), and who mainly serve to trigger reminiscences about his own youth, which was infinitely more compelling than theirs.

Every individual in the class of 13 (even the one who is absent) is named, described, and given at least one phrase to mutter, and by the end, Codrescu is able to divide the students into two types: the “restless ironic” and the “mordant, obsessive,” with two pupils falling somewhere in between; but for the reader, the students remain more dead than alive, which is perhaps the point with undergrads in creative writing courses. Even Matthew Borden, the precocious heir to a milk fortune — whose grandmother was a friend to Queen Marie of Romania and is buried inside a life-size bronze statue of Diana the Huntress that stands in their family cemetery, in a decommissioned nuclear silo — remains unaccountably flat, particularly in comparison with Codrescu, the outrageous, inappropriate, highly articulate anti-academia professor, who refers to himself as “the typical fin-de-siècle salaried beatnik” and a “doddering old f**k.” He makes thorough use of the verb “google,” as in, “This is a poet that you will study all semester, read deeply, understand well, google till you’re satisfied,” and mentions recent cultural phenomena such as Facebook with detached amusement.

He remembers fondly when you could smoke in the classroom, but “these aren’t the old days. Are these even ‘days’ anymore?” Finally, after returning from a bathroom break, he realizes that his students are staring at him, and not because he left his zipper open or peed his pants, but because he is a perfect anachronism — a fossil. “A fossil is immortal because it has moved out of Fast Human Time (FHT) into Instructive Slow Time (IST).” This moment comes toward the end of this slim not-novel and strives to be “the moment,” but only half-heartedly. Codrescu recovers, as always, too readily returning to his energetic, joking, embittered but not bitter mode and propelling everything forward at great speed, perhaps in order to get to the end of the book as quickly as possible so that he can get home to Laura, his wife.

Beneath Codrescu’s wacky, self-amused teaching methods, perfected poet-in-a-phrase descriptions, off-kilter teacher-student dialogue and old-timer digressions, there can be found a pestering ambivalence toward the university and a suspicion that he is a hypocrite. Referring to his early days as a professor, he says, “at the very beginning of this fraudulent enterprise….” And: “I pissed smugly on academia, which is a way of saying that I pissed on myself, which I do, regularly, to extinguish my pretensions…. The professors are not afflicted by the identity crisis that is my only subject.” Once again, this sort of rhetoric is only the striving for an underlying darkness; Codrescu’s inability to be consistently gloomy hinders any occasional attempt. But the main problem is that it’s too late for Codrescu to be writing of his ambivalence. He is about to retire. Having made it through to the end, the identity crisis that maybe once was his only subject has gone stale, leaving in its wake a stereotypically nutty professor who has a way with the students and knows it.

By far, the most affecting aspect of the book is not what remains of Codrescu’s earlier dilemma, to teach or not to teach, but the tangible remains of decades in the classroom. As it seems to me, he has come away with two things: a preoccupation with urine — “My students started returning, one by one, ounces of urine lighter,” and, “Their bladders were ready to burst. Ah, merciless poetry! I saw myself covered in the golden showers of their bursting bladders,” just two examples of many — and the sad knowledge that all the skeptics are wrong: — “Unfortunately, poetry was exceedingly teachable.”

Yelena Akhtiorskaya is a writer living in New York City.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 3

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 4

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion Gaza and Trump have left the Jewish community at war with itself — and me with a bad case of alienation

-

Fast Forward Trump administration restores student visas, but impact on pro-Palestinian protesters is unclear

-

Fast Forward Deborah Lipstadt says Trump’s campus antisemitism crackdown has ‘gone way too far’

-

Fast Forward 5 Jewish senators accuse Trump of using antisemitism as ‘guise’ to attack universities

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.