Jerusalem Riots Expose New Rift Between Religious Zionists and Authorities

Image by Getty Images

Unrest: Right-wing settlers battle Israeli police outside Israel?s Supreme Court after a protest against the interrogation of Rabbi Dov Lior, the controversial chief rabbi of Kiryat Arba. Image by Getty Images

When right-wing Jews burned tires in the streets of Jerusalem and tried to break into the compound of the Israeli Supreme Court in late June, they were marking a new stage in the development of a growing movement in Israel.

The declared target of their angry protest was the arrest for a two-hour interrogation — and subsequent release without charge — of Rabbi Dov Lior, a 77-year-old Holocaust survivor and one of Israel’s most respected poseks, or determiners of Jewish law.

But Lior is also a controversial sage who affirms, among other things, that it is “permissible for the Israel Defense Forces to attack in the course of warfare a civilian population that is ostensibly innocent of wrongdoing.” This position is informed by Jewish morality, and Jews “should not feel guilt out of the morality of unbelievers,” he claimed in a 2004 ruling.

To his followers, Lior’s brief arrest confirmed their belief that a Kulturkampf, or culture war, is being waged in Israeli society, in which the secular-dominated state establishment is constantly trying to undermine the religious public and its lifestyle.

This has been a working assumption for decades of Israel’s black-hatted ultra-Orthodox Jews. But Israel’s Religious Zionists, from which the bulk of Lior’s followers come, have traditionally upheld the legitimacy of Israel’s secular authorities, until relatively recently. Over the past 15 years, some members of this movement have moved closer to the ultra-Orthodox’s view of Israel’s secular authorities as legal and moral usurpers, with volatile consequences. The new movement is known as hardal, a combination of the words Haredi, as the ultra-Orthodox are called in Hebrew, and dati-leumi, or Religious Zionists.

Buoyed by the claim that the secular state betrayed Religious Zionists with the Gaza evacuation of 2005, the hardal ideology has become increasingly popular over the past six years. Sources in academia and politics were reluctant to venture an estimate of their numbers. But all agreed they exceeded 100,000 adherents.

The arrest of Lior, one of their leaders, was related to conclusions he has articulated about Jewish religious law and its requirements that secular authorities find racist and potentially seditious. Among other things, his scholarship has brought him to the conclusion that soldiers must disobey orders if told to evacuate settlements, that it is prohibited to employ Arabs or to rent homes to them, and that children produced by sperm donations from non-Jews are at risk of inheriting “negative genetic traits that characterize non-Jews.”

In various speeches that Lior has given since his arrest he has stressed that religious law, as he interprets it, takes precedence over state law. “Israel’s rabbis must express their views without fearing that some may not like it,” he said on July 4. “The people of Israel’s power is its spiritual basis.”

Police arrested Lior, who is chief rabbi of Kiryat Arba in the West Bank and de facto chief rabbi of nearby Hebron, along with Rabbi Yaacov Yosef, the son of Sephardic Jewry’s premier spiritual leader, Ovadia Yosef, for suspected incitement to violence by virtue of the public endorsement both gave to the controversial book Torat Hamelech (“The King’s Torah”). Written by hardal scion Yitzhak Shapira of the settlement of Yitzhar, the book finds that babies and children of Israel’s enemies may be killed, since “it is clear that they will grow to harm us.” It also states that “the prohibition ‘Thou Shalt Not Murder’” applies only “to a Jew who kills a Jew,” and it terms non-Jews “uncompassionate by nature,” adding that attacks on them “curb their evil inclination.”

For many Israelis, the Lior and Yosef arrests sent out an impor tant message that the government will act against what it views as incitement to violence and that it will not give special treatment to those with high status. “Nobody is above the law — and I demand that every Israeli citizen respect the law,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said at the July 3 Cabinet meeting, echoing an earlier Justice Ministry statement.

But others saw the arrests as evidence of double standards, with the religious hard-line being denied free-speech rights enjoyed by others. “It’s a discrimination of ideas: Academics are free to say and write whatever they want, but when it comes to rabbis, it’s unacceptable that a different rule applies,” said Yishai Fleisher, a settler activist and broadcaster on the right-wing Galei Israel radio station. Such an arrest in America “would be seen as shocking” he said, adding that Israeli liberals betrayed their philosophy by supporting it.

In fact, some on the left questioned the arrests, among them the liberal daily paper Haaretz in an editorial, which asked why authorities have not instead fired Lior from his position as chief rabbi of Kiryat Arba, a government position.

Nevertheless, some figures from the more moderate dati-leumi community echoed Fleisher’s criticism. Haim Druckman, head of the mainstream Orthodox Bnei Akiva network of yeshivas and former head of the state’s Conversion Authority, told a July 4 demonstration drawing some 1,200 protesters that law enforcement bodies were being “selective” in taking action against the religious right.

Though the arrest of any hardal rabbi would touch a raw nerve, Lior’s revered status made the reaction to his arrest especially volatile.

“At this point, Dov Lior is probably the leading Religious Zionist posek around,” explained Shlomo Fischer, a fellow at the Jerusalem-based Jewish People Policy Institute.

Unlike some other rabbis of the religious far right, Lior is seen widely as a genuinely gifted scholar. “He’s a very legitimate and important talmid hacham [sage]. On any other issue I respect his rulings,” said Fischer, a founder of the Yesodot Center for Torah and Democracy, which promotes democratic values in the Orthodox community.

Michael Karpin, author of the 1998 book “Murder in the Name of God: The Plot To Kill Yitzhak Rabin,” about alleged incitement by Lior and other rabbis against Rabin before his murder, said that Lior’s importance stems from the fact that “he’s able to be part of the establishment and part of the extreme right.” Besides his high reputation as a scholar, his state position as Kiryat Arba’s chief rabbi makes him “like a present” for the far right, said Karpin.

Silesia-born Lior shot to fame in 1995, after Rabin’s death, when it emerged that earlier that year, he had co-signed a letter sent to 40 rabbis, asking for their thoughts on whether Rabin, for moving forward with the Oslo process, was a “moser” — a Hebrew term for a “traitor” — who is, according to Halacha, deserving of death.

Prior to this, Lior also called Baruch Goldstein, the settler who massacred 29 Muslims at prayer in Hebron in 1994, before he was beaten to death, a “martyr.”

Many Israelis have taken the reaction to Lior’s arrest as a glimpse of what may unfold if Israel attempts any significant evacuation of settlements in the occupied West Bank — especially in Lior’s district, Kiryat Arba and Hebron. “Because of this, a lot of people will think that it’s difficult and maybe impossible to evacuate,” said Avishai Ben Haim, religious affairs commentator with Israel’s Channel 10 television station.

Contact Nathan Jeffay at [email protected]

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture In a time of tariffs and uncertainty, this is the Jewish word we need to soothe our minds and souls

-

Opinion As Zionist Jews, we must condemn Trump’s campaign to deport students

-

Opinion Trump is cracking down on universities — just like Hitler targeted academics who didn’t bow to his will

-

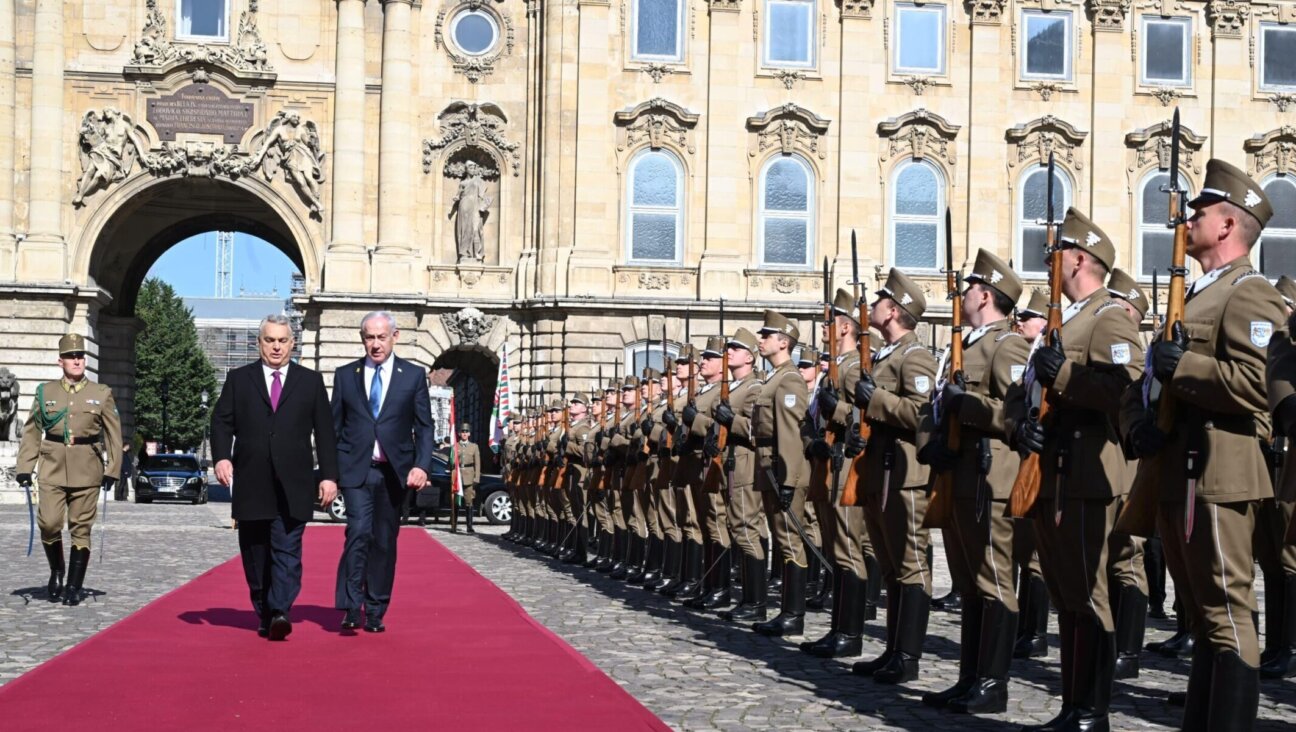

Fast Forward As Netanyahu arrives in Budapest, Hungary announces exit from International Criminal Court

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.