Lost Music of Istanbul’s Sephardic Jews

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

‘It’s really changed.”

My wife, Ingrid, and I were sitting in the lobby of the Hotel Residence in Istanbul, listening to an Israeli historian named Daniel wax nostalgic. Daniel’s mother, a native Istanbulu, had taken him there on frequent childhood visits in the years before the varlik vergisi, or “wealth tax,” of the 1940s and the Istanbul pogrom of 1955 — an attack aimed primarily at the city’s Greek population that spilled over onto its Jewish and Armenian ones, as well — persuaded many in its once-thriving Jewish community to leave. (Many had already left by the early decades of the 20th century, spurred by the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of Turkish nationalism.)

We told Daniel that we planned to take the ferry to the nearby island of Buyukada. Hence his wistful remembrances of days long past: of summers spent on the island as a child, surrounded by Jewish and Greek families seeking refuge from the stifling heat of the city, and of Jewish men in shirt sleeves playing cards on the porches of wooden villas. “There were so many Jews there, the Turks called it ‘Yahudikada,’” Daniel said.

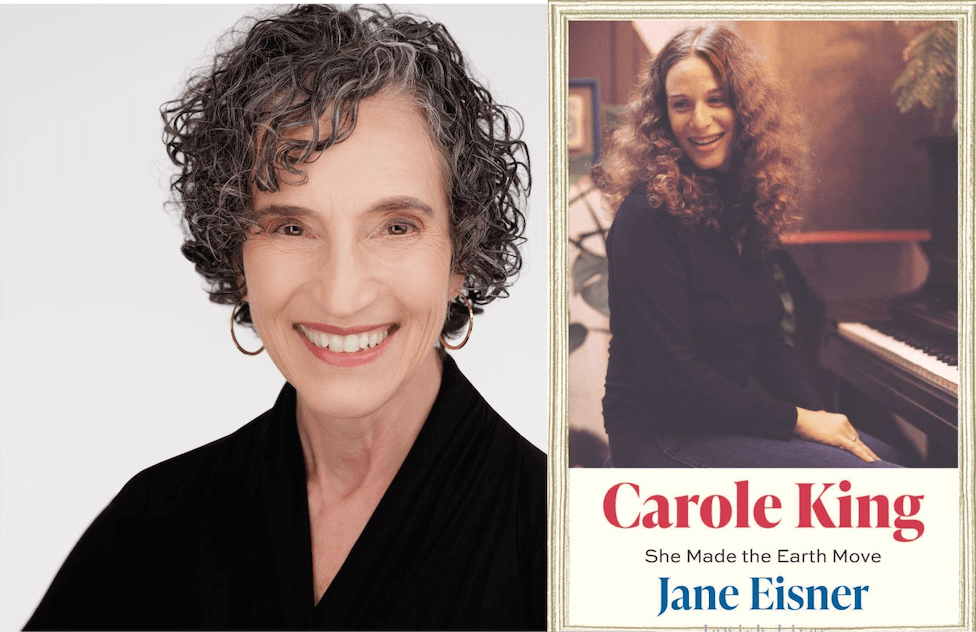

Banging a Drum for Piyyutim: Ethnomusicologist and bandleader, Samuel R. Thomas plays in the WNYC Greene Space. Image by Aaron Epstein

They don’t call it that anymore. Given Istanbul’s historic importance as a center of Jewish life and culture — Sephardic Jews began settling there en masse during the Inquisition, and at its peak, the Ottoman Empire gave the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry a run for its money — I was struck by how little remained of its Jewish community, and by the lack of Jewish music in particular.

If that seems like an oddly parochial observation, so be it. The Ottoman Empire essentially gave birth to the Eastern Sephardic musical tradition — a richly seasoned stew of Iberian, Turkic, southern European, Mediterranean and Romani ingredients whose appeal extended beyond Europe to the New World. Early klezmer musicians absorbed bits and pieces of it while working the southern reaches of the Empire with their Roma counterparts prior to the 20th century, and Turkish immigrants like Jack Mayresh and Victoria Hazan served it up on American 78 RPM records with lashings of Turkish, Greek, Hebrew and Ladino. Jewish music has always borrowed from many sources, but the Turks made it into a veritable melting pot long before the English playwright Israel Zangwill popularized that particular metaphor.

Which is why I was saddened to see that so few traces of it remain, at least in Turkey itself. Saddened, but not surprised: We couldn’t find much traditional Turkish music of any kind, from classical Ottoman fasil to Romani dance music — the latter having been relocated along with its practitioners when the Turkish government razed Sulukule, one of the oldest Roma settlements in the world, in preparation for Istanbul’s turn as cultural capital of Europe in 2010. Just in case the irony was lost on the minister of culture, Ingrid, a percussionist with a soft spot for Romani rhythms, sent him an e-mail congratulating him for having destroyed a sizable chunk of his country’s cultural heritage.

The contrast with Turkey’s past is even greater when compared with America’s present. Ingrid and I were in Istanbul in late April. Barely two weeks before we left New York City, the ethnomusicologist and performer Samuel R. Thomas took to the airwaves on public radio with a collection of Brooklyn-based rabbis and musicians to play and discuss a selection of piyyutim, the liturgical poems that are set to music throughout the Sephardic diaspora. There were traditional melodies performed in regionally accurate styles from old Ottoman possessions like Egypt and Syria, and some jazzy new arrangements by Thomas. All of it was lovely, and you’d be hard-pressed to find anything like it in Istanbul, the former hub of the Sephardic musical world. (Thomas recently released a new CD, “Resonance,” featuring some of the same material.)

Istanbul’s historic role as a transformative funnel for the music of Sephardic Jewry was long ago taken up by Israel and America. Shortly after we returned to New York, “Atonement,” an oratorio by the composer Marvin David Levy (best known for his opera, “Mourning Becomes Electra”), had its world premiere at Temple Emanu-El on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Former New York Governor Mario Cuomo narrated the middle movement, “Inquisition,” which uses Ladino song and Hebrew liturgy to explore the Hobson’s choice offered to Iberian Jews in the 15th century: Convert, flee or die.

This, in turn, was just a couple of months after Yasmin Levy, an Israeli singer who performs contemporary Judeo-Spanish pop (her latest album, the slickly produced “Sentir,” was released in January), appeared with the Brooklyn-based group DeLeon, which welds Sephardic melodies onto an indie-rock chassis. (In the “it’s a small world” department, Levy’s father was a Turkish émigré who headed the Ladino department of Israeli state radio.) And in December, the annual Sephardic Music Festival will once again present a roster of American, Israeli and Israeli ex-pat musicians performing a spicy array of material (electric, acoustic, traditional, contemporary) from all across the Sephardic spectrum in various Manhattan venues.

Music history is complicated, and centers of activity can shift for many reasons, pushed hither and thither by everything from changing tastes and shifting economic circumstances to immigration and war. But that all of this creative energy should be flowing not in the old Sephardic diaspora, but rather in the new one, probably says something about how different places, in different eras, respond to the ethnic and religious minorities that provide so much of their diversity and dynamism. With some notable, and horrible, exceptions (see: genocide, Armenian), the Turks may have scored higher marks under the Ottomans than they have in recent years. America, on the other hand — a country whose own empire appears to be in serious decline — is still doing something right.

Alexander Gelfand is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Economist and (his favorite) Bartender Magazine.