Ironies Behind A Stunning Synagogue

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Light in the East: Beth Sholom at night, viewed from the northwest. Image by balthazar korab ltd

Beth Sholom Synagogue: Frank Lloyd Wright and Modern Religious Architecture

By Joseph M. Siry

University of Chicago Press, 736 pages, $65

When Rabbi Mortimer J. Cohen contacted Frank Lloyd Wright in November 1953 about designing a new sanctuary for his conservative congregation, Beth Sholom, in the Philadelphia suburb of Elkins Park, the legendary architect had never designed a synagogue since beginning his architectural career 60 years earlier, in 1893. This striking fact appears nearly midway through architectural historian Joseph M. Siry’s important new book, “Beth Sholom Synagogue: Frank Lloyd Wright and Modern Religious Architecture.”

But it raises two fundamental questions about the origins of what is arguably America’s most famous postwar Jewish house of worship. Why, given Wright’s inexperience in synagogue design, did the architect take on the commission? And why did Wright take so long to build a synagogue in the first place?

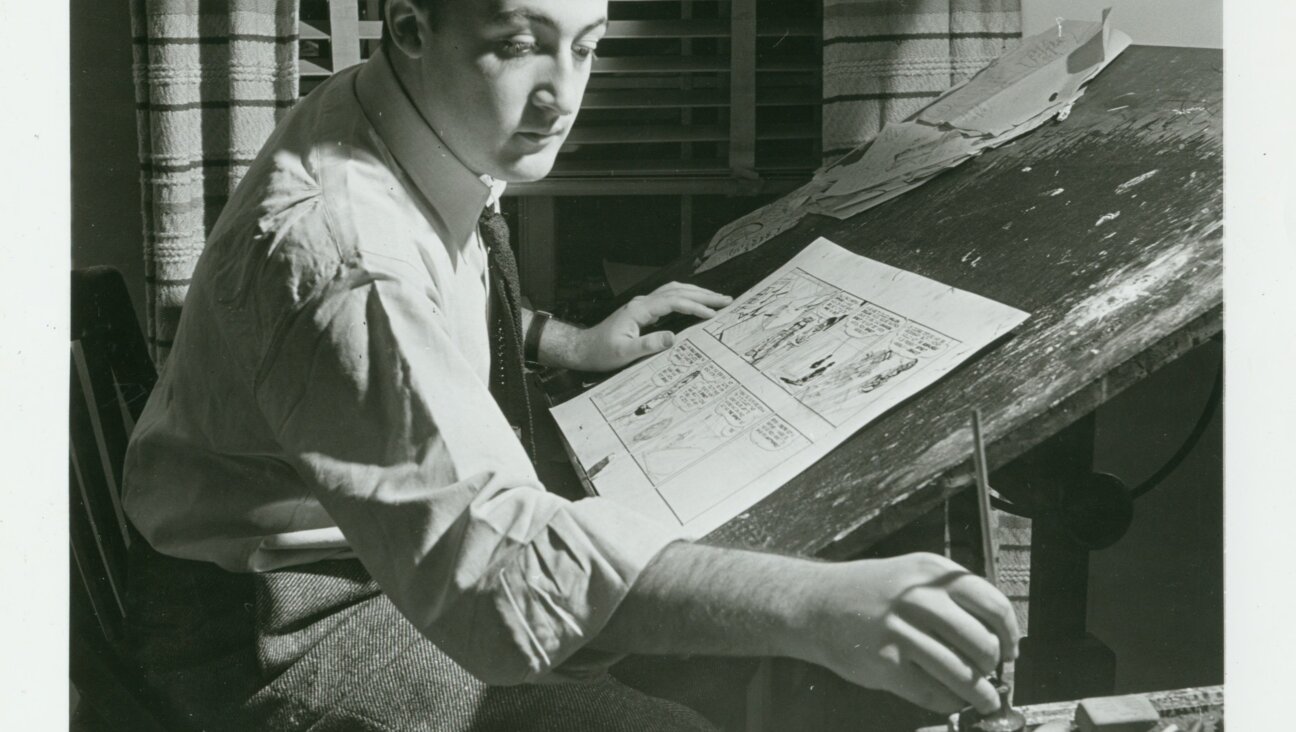

Frank Lloyd Wright Image by getty images

In explaining his motives — and why Cohen sought him out to begin with — Siry probes deeply into multiple architectural, cultural and religious contexts. The result is that “Beth Sholom Synagogue” is a massive tome. Published in an oversized format and weighing nearly 6 pounds, it contains more than 700 pages of text (including notes) and hundreds of architectural drawings and photographs. It is a beautifully produced work of art in its own right, and it is certain to be the definitive work on its subject. Casual readers may not have the sitzfleisch, or endurance, to give Siry’s extremely detailed analysis the close reading it merits, but those who do will find their efforts rewarded.

Following a brief introduction, Siry spends the first half of his book laying out the larger biographical and architectural contexts for Wright’s design. He explains how the architect’s Unitarian religious background led him to develop a respectful attitude toward Judaism. He discusses how Wright’s experience working at the Chicago firm of Adler & Sullivan exposed him to innovative synagogue designs at the turn of the century, most notably the comparatively modern Kehilath Anshe Ma’ariv, which opened in 1891.

And he shows how the architect’s designs for a series of Christian churches and chapels between the late 1920s and early ’40s helped Wright develop his own unique solution to the central architectural question of how to make a modern construction that would signify a denominational ideal.

After laying out this detailed context, Siry shows how it informed Wright’s plan for Beth Sholom. Counterintuitively, the most notable aspect of Wright’s design was that he devised it not by himself, but in collaboration with Cohen.

Cohen was unusual among postwar American rabbis in taking a direct role in the design of his sanctuary. Like other postwar rabbis who were moving older urban congregations to new suburban settings, he rejected the derivative historicist designs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and aimed for a synagogue that was distinctively modern. Yet because Cohen also wanted it to be identifiably Jewish, he sought out Wright, whose “organic” brand of architecture was opposed to the sterile machine aesthetic of the International Style, and allowed for the great expression of symbolic content.

Following extended discussions in which Cohen made suggestions to Wright about everything from the synagogue’s plan to its interior furnishings, the two men agreed on an elaborate symbolic agenda for the structure. Beth Sholom was designed to evoke the site where Judaism first began: Mount Sinai.

As Cohen explained, God had granted the Torah to the Jewish people there and asked them to build for him a traveling sanctuary. This initially assumed the form of a tent, or mishkan, but later it developed into the synagogue. Cohen added that the sanctuary should radiate light, reflecting both the Jewish (the ner tamid, or eternal flame) and the American symbol (the Statue of Liberty). This appealed to Wright’s American patriotism and coincided with the American Jewish Tercentenary of 1954. Before long, both men were referring to Beth Sholom as a “traveling Mount Sinai of light.”

Having drawn up a plan of action with Cohen, Wright proceeded to translate his vision into architectural form. In doing so, he drew on earlier religious projects that entirely lacked a Jewish basis. Ironically, the most important of these was his unrealized Steel Cathedral project, from 1926.

Designed in the form of a massive pyramid for the congregation of Episcopalian priest William Norman Guthrie in New York City, the Steel Cathedral project has long been recognized by scholars as an important influence on Beth Sholom. Siry, though, adds considerable explanatory detail, showing, among other things, that Guthrie intended the building to serve a “universal religion.” This fact somewhat lessens the incongruity of Beth Sholom having been partly inspired by a church. Cohen, according to Siry, probably did not know of the Steel Cathedral project’s existence, but he probably would not have cared, since his elaborate symbolic agenda for Beth Sholom guaranteed that the synagogue’s identity would be unmistakably Jewish. Indeed, while Beth Sholom’s unique tetrahedral form and abundant glass derived from the cathedral’s pyramidal design, the synagogue was graced with multiple Jewish features, ranging from abstracted menorahs on the building’s exterior steel frame to geometrically rendered winged seraphim above the ark. These features convinced Cohen that Beth Sholom was a truly Jewish, American and modern work of architecture.

In meticulously chronicling the building’s design history, Siry has produced a study that is unprecedented in its thoroughness. Yet he omits material that might help answer the question of why it took Wright 60 years to design his first synagogue.

Here the answer may be less flattering to Siry’s protagonist than the author might have us believe. As several recent studies have shown, Wright was known for harboring anti-Semitic views that are hard to square with Siry’s positive portrait of the architect. Nowhere in “Beth Sholom Synagogue” is it mentioned that Wright often hurled anti-Semitic invective at Jewish employees at his Taliesin house and studio; that he made anti-Jewish remarks about Jewish architectural colleagues, such as Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler, or that he sympathized with the anti-Semitic and isolationist ideas of Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh before and during World War II (Wright’s charge that Jews were warmongers cost him his friendship with Lewis Mumford).

These uncomfortable facts lead one to wonder whether Wright’s inexperience with synagogue architecture may have been deliberate. Might he have rejected synagogue commissions out of prejudice? Alternatively, might Jewish congregations have stayed away from hiring him as a result of his reputation? To be sure, Wright worked for many Jewish clients (most famously Edgar J. Kaufmann and Solomon Guggenheim) but he did so always on secular projects. This changed only after World War II, with the Beth Sholom commission.

Did the legacy of the war and the Holocaust play a role in leading Wright to change course? Given the fact that Philip Johnson designed the famous Port Chester, N.Y., synagogue Kneses Tifereth Israel around the same time for free, partly as a gesture of atonement for his own anti-Semitic past, it is not inconceivable that Wright might have had similar feelings about his wartime position and therefore took on the Beth Sholom project to help rehabilitate himself. The relevance of the war years is further suggested by Siry’s passing references to the Holocaust’s importance to Wright’s co-designer, Cohen.

In the end, the question of Wright’s past should not overshadow the importance of Beth Sholom or of Siry’s impressive volume. At the same time, it would be a mistake to overlook the irony of America’s most famous postwar synagogue having been designed by a one-time anti-Semite.

Gavriel Rosenfeld is associate professor of history at Fairfield University. His “Building After Auschwitz: Jewish Architecture and the Memory of the Holocaust” (Yale University Press) was a 2011 finalist for the National Jewish Book Award.