Obama’s Presidency Renews Activists’ Memories

As Barack Obama took the oath of office as the 44th president — and first black president — of the United States on January 20, there was, across the country, a scattered group of Jews whose perspective on the unprecedented event was deeply personal. The significance of disproportionate Jewish involvement in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s has been much discussed and debated, but there is no denying that large numbers of Jews threw themselves into work for civil rights as organizers, lawyers, marchers, journalists, and in other ways.

For these Jews, Obama’s inauguration as president of the United States is not just a historical watershed; it is a personal vindication of one of the central experiences in their lives. Their experiences, in turn, are an important part of the American Jewish story in the 20th century. Here are the thoughts and remembrances of some of these individuals, in their own voices, on the occasion of Obama’s inauguration.

Jack Greenberg, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s former director-counselor, who helped argue the landmark 1954 school integration case of Brown v. Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court:

“Brown v. Board of Education was extrapolated to mean you couldn’t make racial distinctions of any sort. We had no idea that Brown was going to signify this. We didn’t know it would carry beyond public schools. It quickly transformed America. It was extrapolated not only to all sorts of activities beyond public schools with blacks, but was one of the instigating forces of the women’s rights movement and all sorts of types of discrimination, like age and sexual preference. All those efforts took energy from Brown.”

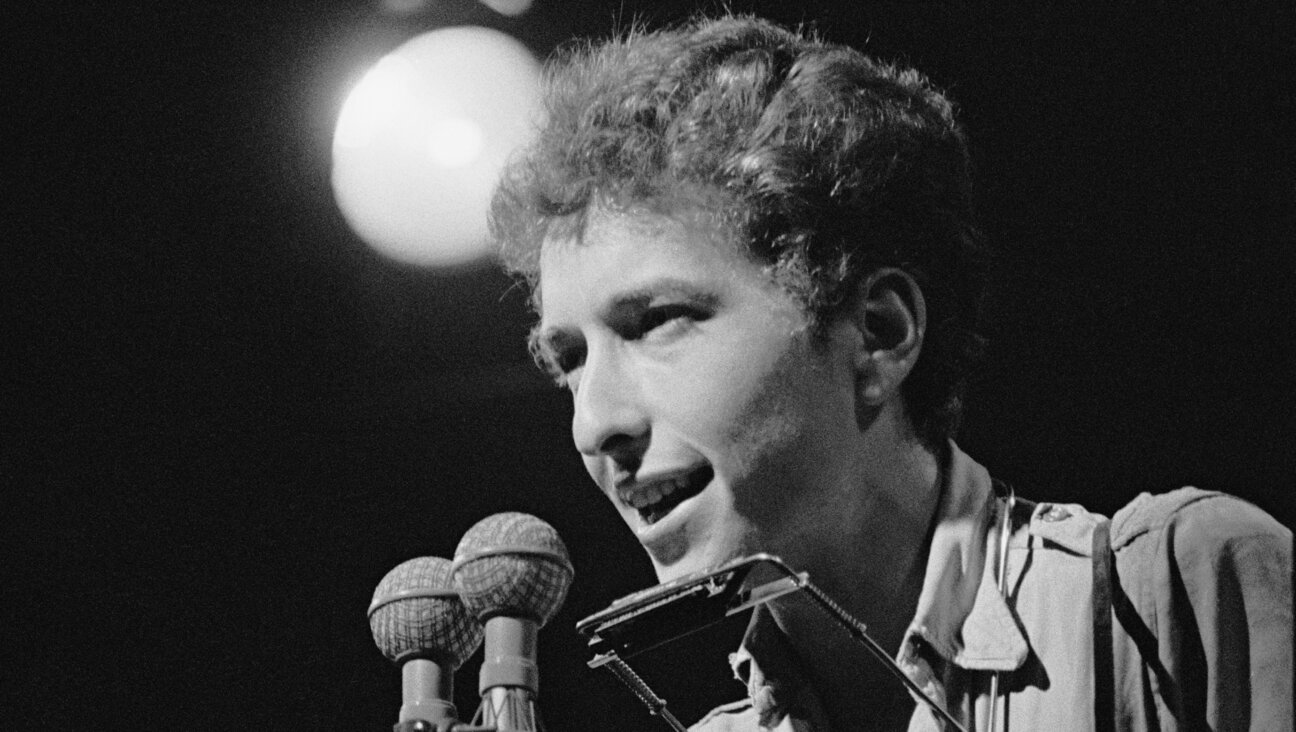

Calvin Trillin, ***a journalist, was posted in Atlanta as a reporter for Time magazine in the early 1960s: ***

“I happened to be there at a busy time, from the fall of 1960 to the fall of 1961. That was the height of the Atlanta sit-in movement, New Orleans school integration, Freedom Rides and the University of Georgia integration. That’s when I realized that [being a journalist] was what I wanted to do. I still could’ve said, if something doesn’t work out, I can always go to law school. After a year, I knew I would never go to law school.”

Lew Kreinberg, a retired Chicago community organizer, recalls a visit to Selma, Ala., in 1965:

“A bunch of young kids from Selma — they must’ve been in their early teens down to 6 and 7 years old, about 50 of them — they decided that they were going to march without any leadership. The Selma police, there were 30 of them, each one of them weighed over 300 pounds. They were bigger than football players, and they were all geared up. They had helmets, they had clubs, they had their rifles, they had their guns. The kids were marching straight into them.

“Stan Harris, who was a member of the church federation, said, ‘Lew, the kids are marching right into those police.’ He said, ‘Lew, come with me.’

“About five of us stood between the kids who were marching, so were marching slowly, and the police with their bayonets out. I was not geared up for this bravery. Somehow I looked at this [policeman] and said, ‘Do you know what you’re doing?’ I tried to get the guy’s attention. He looked up and he saw me, I was a 6 foot 2 inch skinny bearded guy, and he took the end of his rifle and whipped it up against my head. I fell to the ground, which stopped just about everything.”

Charney Bromberg,*** a veteran of Jewish communal affairs who has worked for the Jewish Council on Public Affairs and Meretz USA, was working in Canton, Miss., in 1965, one year after the Ku Klux Klan murdered Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney — two Jews and a black man, all active in voter registration:.***

“George Raymond [a black civil rights organizer] had been badly beaten two weeks before leading a demonstration in Scott County. On the way back from the memorial [for Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney], George rode with me, and we got stopped in the town where he had been beaten. Somehow I managed to avoid a ticket even though I still had a New York driver’s license, and we avoided arrest. My punishment for the good deed was, George asked me if I would take over as the project director in Scott County. He took me out into the rural area the next day to meet families there. Later in the summer, I was arrested a few days after the Voting Rights Act had gone into effect. The Justice Department investigated that arrest as the first violation of the act. That was August of 1965. At that time, I was 21.

“[Later] I felt comfortable being active in Jewish community relations as an advocate for things, for justice in society and for justice for Jews, and I was born into a family that was deeply involved in Jewish affairs. That always had meaning for me. It was all of a piece.”

Rabbi Robert Marx, founder of the Chicago-based Jewish Council on Urban Affairs, worked with Martin Luther King Jr. in 1966 to desegregate housing in Chicago:

“Dr. King came to town and we worked closely together. I found myself speaking at churches on the South Side as a warm-up to Martin Luther King.”

Kreinberg*** also worked with King in Chicago:***

“The open housing marches are what Dr. King and his people did to mobilize folks so they could see that Chicago was as bad as any southern city. They had people throwing bricks at nuns and priests and all the rest. Rabbi Marx, I think he got hit with a brick. It was tough stuff.”

On the role of Southern Jews

Trillin:

“I think in the South, the role of Jews was complicated. There are whole books written about this. In Georgia, the lawyer who fought the county unit system — which was one of the bulwarks of the segregation system — was Morris Abram, who [later became] president of Brandeis and head of the American Jewish Committee. His opponent was Charles Bloch from Macon, who was a strict segregationist. There were Jews on both sides.

“The first time I saw the Klan, they were marching in support of Rich’s Department Store, which I think was traumatic to the owners, because the Klan didn’t like Jews any better than they liked black people.”

Rabbi Marx*** had researched patterns of segregation in the South for the Reform movement in the early 1960s:***

“In Tennessee, there would be a white boycott, you’d hear ‘Don’t go to Cohen’s Department Store, because Cohen is in favor of integrating and he allows blacks into his lunch counter.’ And at the same time I’d see black pickets outside of Cohen’s Department Store saying ‘Don’t go to Cohen’s because he practices segregation.’”

Trillin:

“In the South, New York meant Jewish. There was a feeling in the South, certainly constantly expressed by people like Charles Bloch…that black people in the South were perfectly happy and they were just being stirred up by outside agitators – and it really meant outside agitators from New York, and that meant Jews, or foreigners, or strange dark people.”

Civil rights and Jewish values

Greenberg:

“I am not an observant Jew, but it was Jewish values that got me involved. It was one of

the factors. My parents were immigrants, they were socialist Zionists, they were not very active, though other members of my family were, and so it was a common subject of dinner table talk, the whole question of equality and justice.”

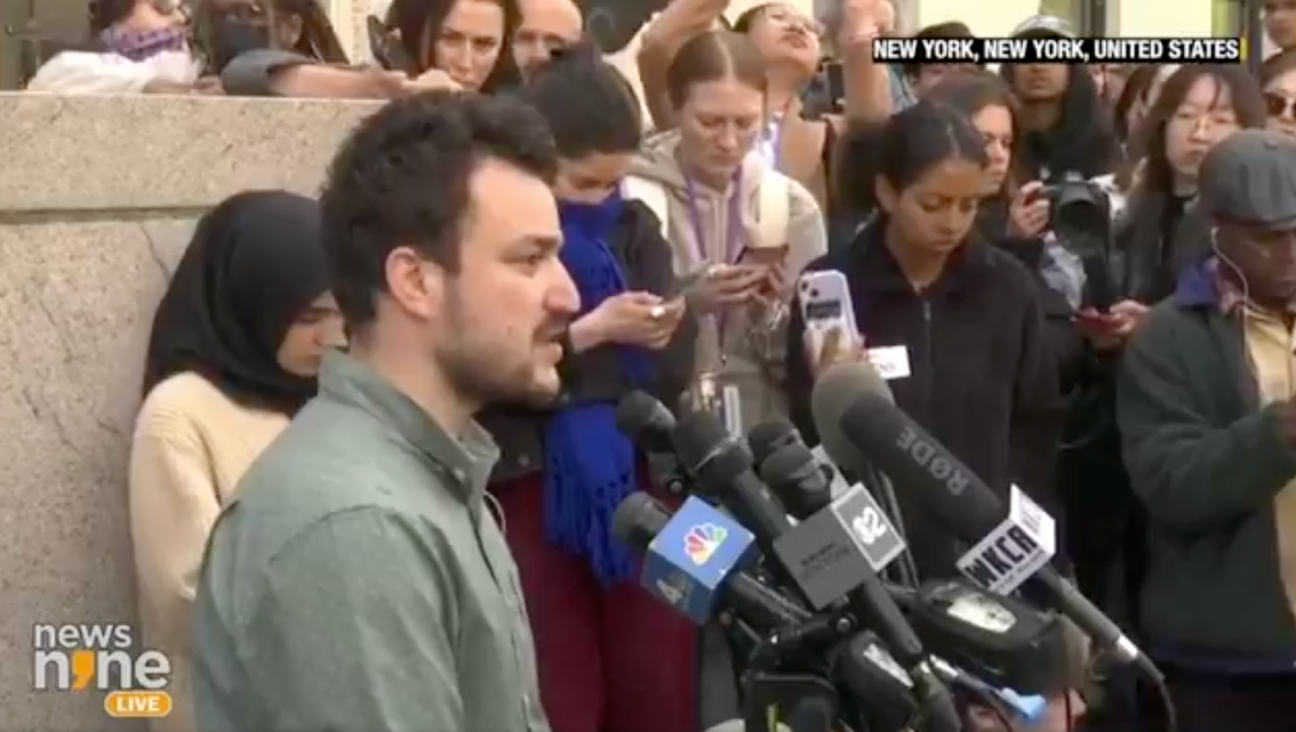

Glenn Richter***, a volunteer worker in New York for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the early 1960s, went on to help establish the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, an early advocacy group for Soviet Jews:***

“I was 18 [when I worked for SNCC]. By mid ’64, several of us in the civil rights movement founded the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry.

“Young Jews were very inflamed by the civil rights movement, they felt it was a cause of great justice…. When the issue of Soviet Jewry came up, we said listen, we’ve been fighting for the rights of other people; what about our own people?”

On the ascension of Obama

Richter:

“I think that it means that American society has moved enormously in the proper direction, even though with all the kvetchers, obviously there’s plenty of racism around going both ways. But I think that for a person who has the name of Barack Obama with a Muslim father, I think obviously it’s something that you can only describe as delicious.”

Marx:

“I think it’s a culmination of years of work. On the other hand, I have a caution, and that is that the media are making so much of the fact that he’s an African American that that provides evidence that African Americans are not yet fully a part of American culture. We don’t make so much of a white person being elected president, but when we make so much of a black person, that shows me that there’s still a lot of work to do.”

Trillin:

“There were times when I was in Alabama and Mississippi when I would have settled for a black cop. Yes, we’ve come a long way, and yet sometimes I think that we’ll never get out from under this, in a thousand years we’ll still have it.”

Kreinberg:

“It’s a miracle. I didn’t expect to see it in my lifetime.… We keep inching along, but there are stars in our sky. If there are no stars in the sky, there’s no sense in having a sky.”

Rebecca Spence and Lana Gersten contributed to this story.