Humor and Terror: A Conversation Between Marcelo Birmajer and Ilan Stavans

At the most recent San Francisco Jewish Book Fair, the Argentinean Jewish novelist Marcelo Birmajer, author of the recently translated novel “The Three Musketeers” (The Toby Press, 2008) — and deemed “the Woody Allen of the Pampas” by The New York Times — spoke to Mexican-American Jewish scholar Ilan Stavans, author of, most recently, “Resurrecting Hebrew” (Nextbook, 2008). Stavans is the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. What follows is an excerpt from their wide-ranging conversation — and their subsequent email exchanges — that explores everything from Latin American-Jewish humor to Isaac Bashevis Singer’s libido to Islamic terror.

Marcelo Birmajer: I suspect being Jewish in Mexico City is far more exotic that being Jewish in Buenos Aires.

Ilan Stavans: It’s a matter of degree. In the Hispanic world, being Jewish always means being exotic. Mexico has approximately 115 million people, of which only some 35,000 are Jewish. … This proves that Mexican Jews are as bizarre as unicorns. In fact, we’re so few, I’m not sure there’s a particular modality of Jewish-Mexican sense of humor. Unlike you Argentine Jews, who can be quite funny.

M.B.: Jewish humor depends on looking at the world from the outside. It’s a survival mechanism. Argentina, as you know, has not been homogenously hospitable to Jews. Argentine-Jewish humor uses irony to [AS? YES] a strategy against the status quo. It is also a strategy against a capricious God, whose actions often appear to be arbitrary. Not to say that I know the formula to explain what makes a Jewish joke work. Jewish humor is often mysterious, even inexplicable. If being a Jew is to understand the precariousness of life, being an Argentine Jew multiplies that quality exponentially.

I.S.: What do you mean?

M.B.: Add to the transient state of Jewish affairs in the Diaspora the fact that in Argentina, life, by definition, is unstable. The only way I myself can handle the daily chaos is through humor, for example, by creating a battalion of antibodies that help me to face the virus one comes across in politics, the economy and society in general. The best way to be an Argentine is tangentially. Take the case of my grandfather Trau. He arrived from Poland to Argentina in 1939. In Poland he lost his first wife and his first daughter, whom he was unable to bring along with him. Thus, for me a financial crisis is never too serious. There are far worse things that might happen to you. This awareness grants me a certain distance.

I.S.: Beyond Argentina, do you believe one could talk of Jewish-Hispanic humor?

M.B.: As far as I’m concerned, there surely is. Maybe it’s presumptuous on my part, but I am an Argentine, a Latin American and, hence, a Hispanic. Thus, Jewish-Hispanic humor exists.

I.S.: Is that enough? For what proof is there that God exists other than ourselves? In the same way, there’s no way to be certain that Latin America exists. To me it’s just an intellectual invention, a convenient concept in the minds of bankers, politicians and cartographers to homogenize a heterogeneous hemisphere. Don’t you agree?

M.B.: I’ve no doubt that Latin America exists, just as I have no doubt God exists. No matter how wide the differences between a Mexican and an Argentine like you and me, I find elements in common. And I’m not talking about Uruguayans now.

I.S.: And God, does He also have a sense of humor?

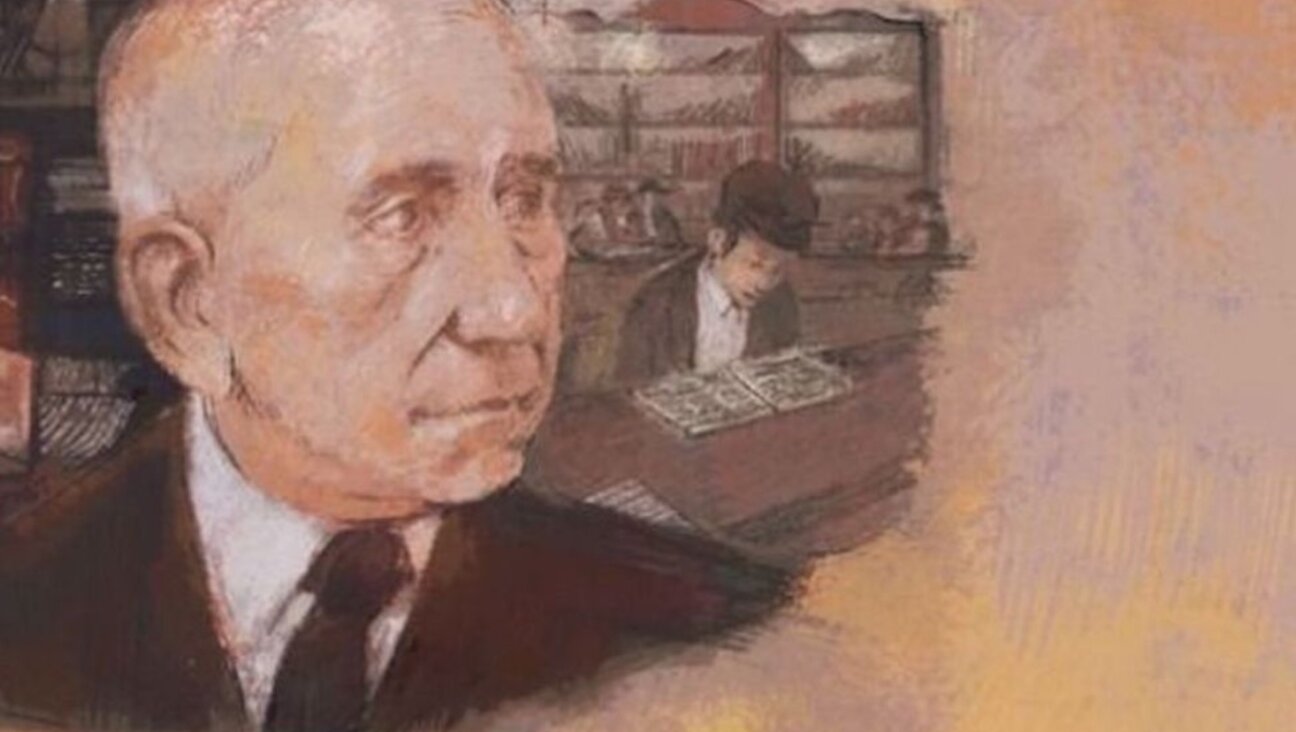

M.B.: I suspect He does. To me, He often appears to be a magisterial joke Himself. But it isn’t the type of joke one can tell during Shabbat. Ilan, let me switch gears and ask you: Since you were the editor of the three-volume “Isaac Bashevis Singer: Collected Stories” [Library of America, 2004], tell me about working on the project and putting together a companion photo album. What unexpected secrets, maybe even jokes, did you discover in Singer’s archives?

I.S.: In his writing, Singer was playful — a simpatico — but in his life he was a rascal. Just as I came across unpublished novels (some of which are illegible) and earlier editions of well-known stories, I also discovered that, on a daily basis, he was abrasive and violent, not to mention a liar. In other words, I learned to appreciate the extent to which a famous writer is also infamous at the mundane level. In your view, what difference is there between reading Singer or, perhaps, Philip Roth in English and in Spanish? Or, for that matter, watching a Woody Allen movie in the Hispanic world?

M.B.: Woody Allen is a Jewish director of universal themes, whereas Singer and Roth are Jewish writers of Jewish themes.

I.S.: What do you mean?

M.B.: Woody Allen has never done a film about the Shoah or about Israel. Instead, these themes are central to Singer and Roth. In Woody Allen’s movies, the characters happen to be Jewish. In Singer and Roth, there would be no plot if the characters weren’t Jewish.

I.S.: You’re quite attracted to the three of them, aren’t you?

M.B.: Woody Allen becomes a focus of attention of any narcissist like me. Singer and Roth are a diversion I enjoy because of their conflictive nature. They entertain me and attract me because they are neither boring nor sophisticated. They don’t make it easy for me to identify with them. What I like most about their oeuvre is the role doubt plays in it. For non-Jews, including those in the Hispanic world, Woody Allen, whom I admire, is a good Jew, a friendly Jew, while Singer and Roth are Jewish and that’s it! Not coincidentally, Woody Allen’s public statements against Israel during the first intifada had a repercussion as wide as that of his films. In contrast, Singer and Roth’s pro-Israel statements, literary and as a matter of opinion, are far less known than their books are. But let me turn the conversation around again: How to explain the fact that two Latin American-Jewish intellectuals are as fascinated with Singer, a Pole who lived in the U.S., as you and I are? Why are we interested in a guy who didn’t speak our language?

I.S.: He did speak two of my languages: Yiddish and English. We owe Singer the reinvention of the shtetl as a habitat not of depravation, but of excessive libido. I’m attracted to his tortured linguistic reveries. In the second half of the 20th century, he wrote in a tongue that was almost extinct, a tongue spoken mostly by ghosts. In any case, in part his loyalty to Yiddish was due to the fact that he could go to bed with his female translators, whom he hypnotized through his imagination as well as his sexual power. Singer was a terror! And speaking of terror, do you think more humor could be extracted from terror? I’m often puzzled by the scarcity of jokes in the United States on Osama bin Laden. In Mexico, there’s an abundance of them.

M.B.: I agree. I also wish there were more jokes about Iran’s current president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

I.S.: And about the leader of Hamas. Does humor flourish in democracy in a way it doesn’t in other systems of government?

M.B.: Making fun of our political leaders is healthy. It’s pathetic, then, that we can’t find any humor in terrorism. It’s time intellectuals in the Western world became less rigid. Not too long ago, there was a global hoopla because an Iraqi journalist threw a shoe at President Bush.

I.S.: It wasn’t a joke, though.

M.B.: I suspect that if an American journalist threw a shoe at Ahmadinejad, the response would be far more serious. There was a time when making fun of leaders was a heroic act. But for us in the West, Islamic figures are off limits.

I.S.: Would you throw a shoe at Argentina’s president?

M.B.: I would never throw a shoe at a democratically elected leader. The Argentine president has satisfied two requisites: She was elected in a legal, legitimate way, and she respects freedom of expression. Not only would I not dare to do such a thing, but I would consider it an insult if a foreign journalist did it.

I.S.: Do you think Arabs lack a sense of humor?

M.B. I can’t speak to that: It’s neither right nor acceptable. But I can say that humor is an essential part of critical thinking. To make fun of power, to make fun of social behavior, to make fun of collective certainties, is to be critical. In the Arab world, dissent is often prohibited. I can’t say that Arabs lack a sense of humor, but I? can say that Hamas, Hezbollah and Al Qaeda aspire to establish a society without a sense of humor and that, in contrast with Western nations, in Iran, Syria and Saudi Arabia, the capacity to poke fun at life is almost nil.

I.S.: Could you make a comedy of the terrorist attack on the AMIA, the Jewish community center in Buenos Aires that was blown up in the ’90s? Or is it taboo?

M.B.: I don’t think there are taboo topics. Proof of it is Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and Singer’s “Enemies: A Love Story.”

I.S.: I’m sorry, but neither of them are comedies.

M.B.: I myself couldn’t make a comedy of those attacks. I simply couldn’t.

I.S.: Why? Has anyone else done it?

M.B.: Not to my knowledge.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO