Scrambled Electoral Eggs

Would-be peacemakers might want to wait before they start popping champagne corks in the wake of Kadima’s election victory. The outcome of the Israeli election has further complicated an already-muddled outlook for the Israeli-Palestinian peace process.

Now, in addition to a Palestinian house divided against itself, we have a divided and dysfunctional Israeli house. Weak leaders — none of whom are much admired or respected by Israeli voters — preside over weak mainstream parties, none of which succeeded in scoring a decisive victory. This renders quite remote prospects for big Israeli decisions on peacemaking.

Kadima’s narrow victory scrambles the electoral eggs. It really leaves only two realistic options for producing a viable Israeli government. Count on the Israeli political system, however, to take weeks, and then some, to sort all this out. The most rational and positive outcome would be a national unity government composed of Kadima, Likud and maybe Labor, which would succeed at keeping the right (particularly Avigdor Lieberman) at bay and create some cohesion and stability in Israeli policy. This is precisely what most Israelis want.

At the same time, given the philosophical differences between Kadima and Likud on peace issues, such a unity government would be hard-pressed to make the historic decisions needed to reach a deal with the Palestinians. There might be a better chance with Syria, but even that would be very tough. Far more likely would be a consensus on how to deal with Israeli security challenges such as Hezbollah, Hamas and, of course, Iran, if the need arises. Big egos and personalities in this government would create stress, but even Benjamin Netanyahu and Tzipi Livni might be able to put these aside if the national interest demands it, and particularly if some form of rotation allows each of them a turn as prime minister.

Equally plausible is a Netanyahu-led government, dominated by the right. The conventional wisdom is that sooner rather than later, a Netanyahu government would find itself in some conflict with just about everyone — the Arabs, the Europeans and even Washington.

We’ve seen this movie at least twice before: A tough-talking Likud prime minister (Menachem Begin in 1977, Netanyahu in 1997) squares off against a determined peace-seeking Democratic president (Carter, Clinton). Circumstances weren’t the same in either case, but anyone expecting a war between Netanyahu and Barack Obama doesn’t understand the situation in Washington or the region.

A Netanyahu-led coalition would likely be unwilling to move on serious negotiations with the Palestinians and would be very tough on security issues. But the former prime minister has grown more mature and pragmatic since his last tenure, and doesn’t want to sour relations with Washington, if he can avoid it.

President Obama, for his part, is not looking for a fight with Israel either, given his domestic priorities. And, in any case, the peace process narrative these days — really more a horror story — leaves him little room to push the Israelis. Hamas is sitting pretty in Gaza; Hezbollah is firmly ensconced in Lebanon; the Iranians are busy enriching uranium; and Mahmoud Abbas and Arab moderates look weaker than ever.

And so a messy political situation in Israel now presents yet another challenge to an already anemic peace process. The new American president will find himself in a tricky situation. Hemmed in by Iran, Hamas, an ineffectual Palestinian Authority and, in Jerusalem, by a cagey Israeli prime minister and/or a dysfunctional unity government, the Obama administration will need to pick its battles carefully. It will need to be firm with Israel on settlements but also reassuring on security. There might even be a chance for some progress between Israel and Syria.

Ultimately, domestic Israeli and Palestinian politics are going to determine how far and how fast Washington can push Arab-Israeli peacemaking. And if the past is any guide, it’s a good idea for the Obama team to keep its expectations realistic.

Aaron David Miller is a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the author of “The Much Too Promised Land: America’s Elusive Search for Arab-Israeli Peace” (Bantam, 2008). He served as an adviser on the Middle East to six secretaries of state.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture In a time of tariffs and uncertainty, this is the Jewish word we need to soothe our minds and souls

-

Opinion As Zionist Jews, we must condemn Trump’s campaign to deport students

-

Opinion Trump is cracking down on universities — just like Hitler targeted academics who didn’t bow to his will

-

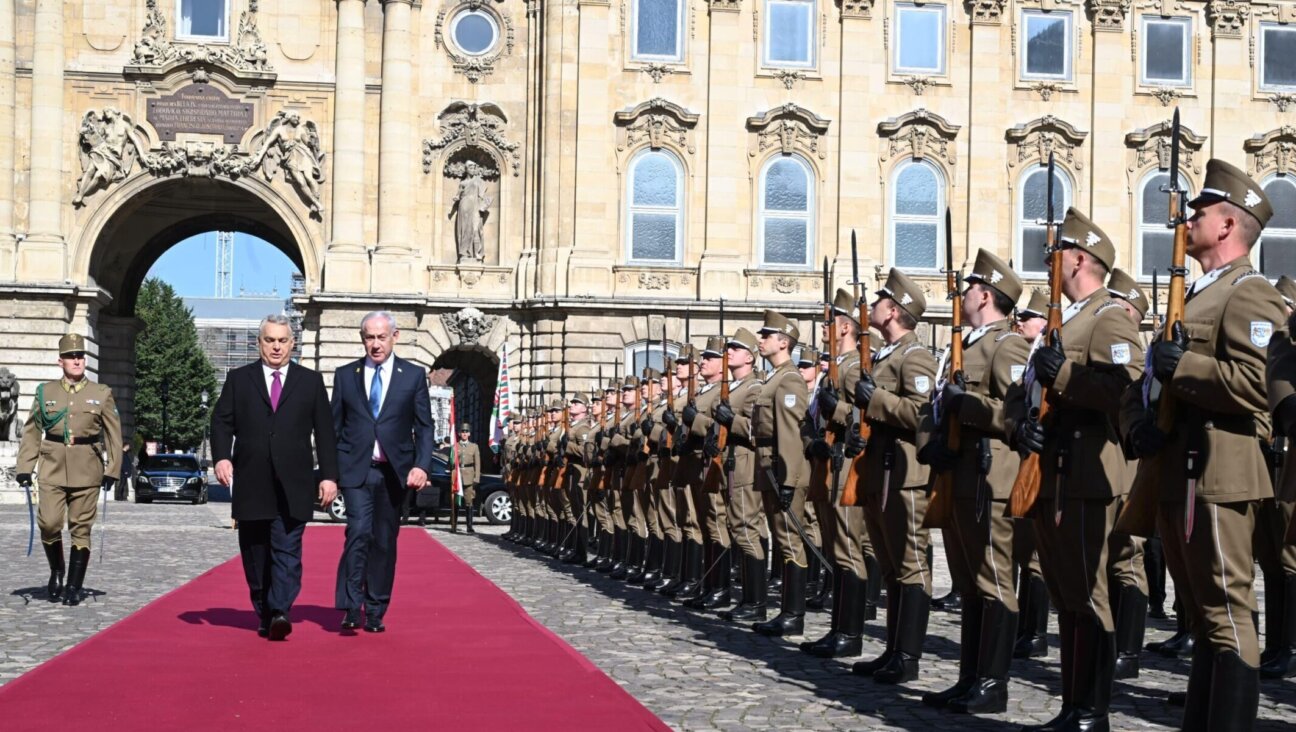

Fast Forward As Netanyahu arrives in Budapest, Hungary announces exit from International Criminal Court

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.