Remembering Mother in Graphic Form

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

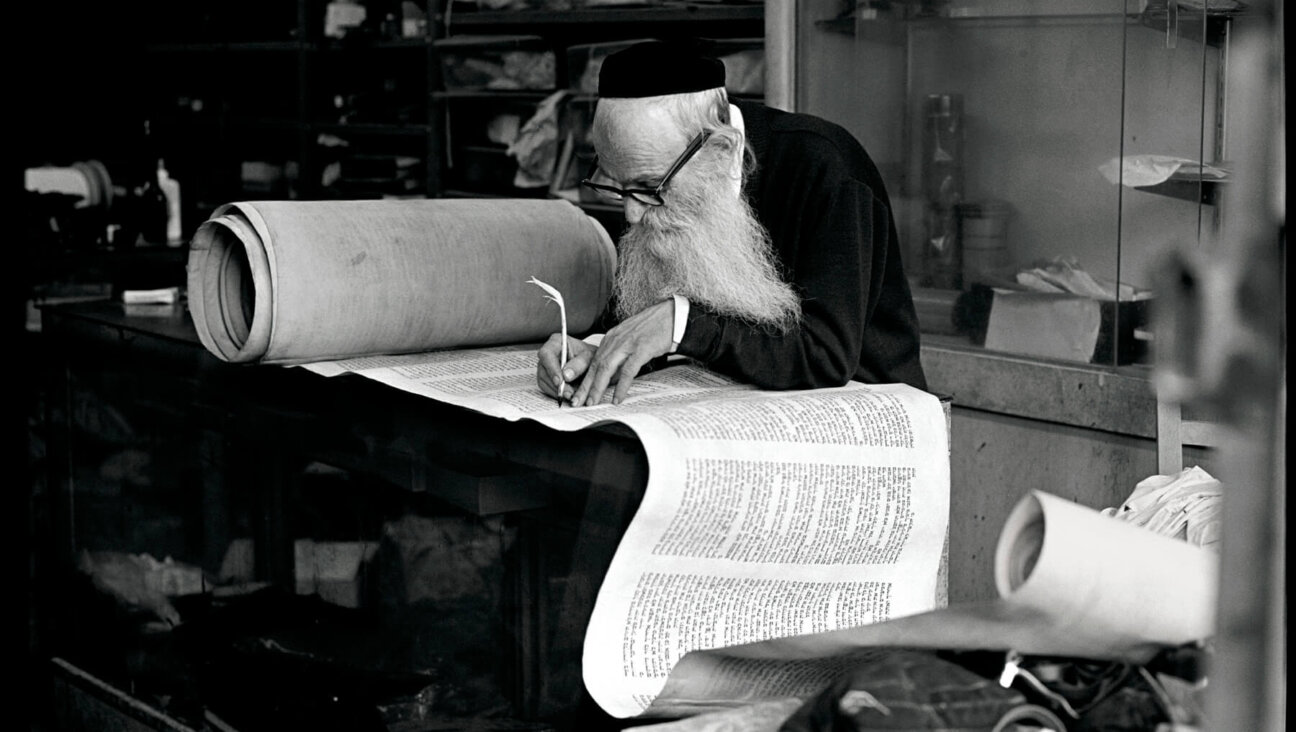

Tangled Tale: Sarah Leavitt tells the story of her mother?s struggle with Alzheimer?s through graphic images. Image by sarah leavitt

Tangles: A Story About Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me

By Sarah Leavitt

Skyhorse Publishing, 128 pages, $14.95

Early on in Sarah Leavitt’s heartbreaking account of her mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease comes what I think of as The Conversation. It’s the moment a family needs but at the same time dreads, when the reality everyone has been avoiding for months or years is finally voiced.

There’s never a good time to discuss a fatal illness with no known cure. But confronting Alzheimer’s in the flesh invites a different level of tragedy — the certainty of descent into a confounding kind of dementia that takes the person you love through a series of new and bizarre personalities. Not for nothing is it called “the long goodbye.”

When my mother was diagnosed, a close friend who is a neurologist looked straight at me and said, with unforgettable honesty, “Let’s hope she dies of something else first.”

So The Conversation is not an easy moment to portray, especially in a memoir like this, which mixes handwritten words with line drawings that in another context might appear childish or whimsical. But Leavitt’s simplicity works in her favor. Just as she gathers the courage to face her parents, Midge and Rob, and to express concern over her mother’s growing forgetfulness and erratic behavior, Midge blurts out, “I have Alzheimer’s.”

The declaration is presented in a black-shaded panel: The obituary feel of it emphasizes the sorrow and aloneness of the statement. I’ve been there. That’s how it feels. Suddenly, it’s very dark and frightening outside. Leavitt nailed it.

I felt that way about the whole memoir; it works. At first, I wasn’t sure whether Leavitt could do justice to the confusing feelings and family dynamics that she aims to portray in “Tangles,” which she calls “a story about Alzheimer’s, my mother and me.” While the genre of graphic novels has grown ever more sophisticated, it’s still a challenge to turn comic book heroes into complicated human beings.

But Leavitt is able to make her characters seem real with a few strokes of the pencil and fewer words. We get the family dynamics: unorthodox, old-style hippie parents who raised two girls — Sarah and her younger sister, Hannah — in a nonreligious household that still felt very Jewish. Sarah is the prodigal daughter, who moves far away to establish her own identity, and then becomes so pulled into the family drama that she becomes its chronicler. The book is interspersed with photographically reproduced snatches of her mother’s deteriorating handwriting and other material that Sarah collected along the way, to document the descent as if to prove it actually happened.

Or maybe that was just a daughter’s way of coping.

Midge was relatively young to be afflicted with the disease, and that adds to the heartbreak for all concerned. After attending Hannah’s joyful Jewish wedding she remembers nothing:

Sarah: “It was fun, wasn’t it, Mom?”

Midge, frowning: “I don’t know. I wasn’t there.”

It’s hard enough for a daughter to witness this in her mother, but it’s crueler still when the disease rips into a family so soon, upsetting the order of things, turning children into caretakers when they still need care themselves. Leavitt portrays the closeness of her relationship with her mother with punch and tenderness.

“God I loved her hands,” she writes early on. “She bit her nails and her veins stuck out all blue and lumpy. They weren’t pretty hands. They were strong hands. Mom hands.”

Sarah Leavitt Image by Teri Snelgrove

But as the disease progresses, Leavitt gives full voice to her own amalgam of confusion, embarrassment, fury and despair. She recalls one of her weekly phone conversations with her parents, when her mother asked her father to leave the room and then railed against him and the world: “I’m a NOBODY! I’m not a REAL PERSON anymore!”

Leavitt writes: “Then she started crying really hard. I decided to pretend she wasn’t my mother so I could manage to stay on the phone and listen to her.” She does, soothing her mother for an hour or so, acting the grown-up. And then when they hang up, Leavitt draws herself prone on the floor, kicking her arms and legs like a child, and screaming, “I want my Mommy!”

Such honesty makes this memoir engrossing and believable. But it also raises the ethical questions that must be asked of any graphic depiction of an Alzheimer’s patient. This is an ugly disease. Midge Leavitt had no control of her bodily functions, undressed at the most inopportune times, said outlandish and hurtful things and acted like a crazy woman.

Yet it was not possible for her to give her consent to this picture of herself. Was Leavitt justified in portraying her mother in such an undignified way? Personally, I couldn’t do it. The few times I wrote about my mother before or after she died, I censored myself heavily, not wishing to publicize the uglier aspects of her behavior.

This is not so much a criticism of “Tangles” as it is a troubled observation, one that I hope Leavitt pondered and discussed with her family before sharing her story with the world.

That concern is tempered by the undeniable love and respect that Leavitt had for her mother. It courses through the story, sustaining her at times of despair, and shaping the mourning that came after her death as well as before it. Though not religiously observant, Leavitt decided to say Kaddish every day for 11 months, reciting the mourner’s prayer on her own.

“I made the Kaddish into my own prayer, my time I spent with her every night,” she writes, depicting herself kneeling on the floor, head to the ground, draped in a shawl with her arms outstretched. “The words of the Kaddish and the cloth against my skin and the solidity of the floor against my forehead comforted me every night.”

As, in the end, this book will comfort any of us who have had to take this journey.

Jane Eisner is the editor-in-chief of the Forward.