Agudath Israel: Abuse Claims Go to Rabbis

Image by youtube

Obligation To Report? Agudath Israel says Orthodox Jews should take allegations of child sex abuse to rabbis before reporting them to police. The position puts it on a collision course with authorities like Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes, who is being scrutinized for his handling of abuse cases. Image by youtube

An Orthodox parent whose child tells him he’s been sexually abused may not take that child’s claim to the police without first getting religious sanction from a specially trained rabbi, the head of America’s leading ultra-Orthodox umbrella group has told the Forward.

But one year after acknowledging that no such registry of trained rabbis exists, Rabbi David Zwiebel said that his group has now dropped the idea of developing one.

One of the main reasons, said Zwiebel, was a warning from Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes — issued only a few days earlier — that rabbis who prevent families from going to police could be arrested.

“If they [rabbis] don’t give the right advice, they can be in trouble,” said Zwiebel. “Why would you want to create some sort of a list that would make them more vulnerable?”

Zwiebel, who is the executive vice president of Agudath Israel of America, said that despite the absence of such a registry, his group would staunchly resist increased public pressure to lift its requirement that parents obtain rabbinic permission.

“We’re not going to compromise our essence and our integrity because we are nervous about a relationship that may be damaged with a government leader,” he said.

Zwiebel’s comments, offered over the course of an hour-long interview in the Aguda’s Manhattan headquarters on May 21, highlighted a growing fissure that has opened between the Aguda and previously friendly senior public officials in New York. The break comes in the wake of a New York Times exposé that chronicled intimidation of ultra-Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn by their own communities to keep them from bypassing rabbinic authorities and reporting abuse. The Times’ two articles, and a flood of media stories that followed, also reported how Hynes appeared to accommodate rather than challenge the ground rules set down by ultra-Orthodox leaders asserting their authority over such cases.

The Times reports followed years of earlier reporting by the Forward, New York’s Jewish Week and other outlets on the issue. In some cases, alleged victims or their parents who went to local rabbis to report abuse were told to keep quiet or suffer severe consequences, or even admonished for raising such charges.

But in the wake of the high-profile attention the Times’ reports generated, even the Brooklyn DA has now forcefully shifted his earlier stance.

In a May 17 interview with NY1, Hynes said rabbis “had no authority” to screen cases of abuse. He said that he told Zwiebel during a meeting last year, “As soon as there’s a complaint of sexual abuse, I expect my office to be… contacted immediately.”

“There was never, ever a suggestion by me that rabbis should filter cases,” Hynes said. He added that a rabbi who dissuades someone from reporting abuse could “end up in handcuffs” if the case turned out to be credible.

In his interview with the Forward, Zwiebel recalled the June 2011 meeting differently. Zwiebel said that when he outlined Agudath Israel’s policy to Hynes, the district attorney did not find anything about the rabbinic consultation process that was “inconsistent with the standards of secular law.”

Indeed, a few days after his NY1 interview, Hynes himself appeared to backtrack. In a May 20 interview on WABC radio, the DA admitted that if a rabbi counsels an ultra-Orthodox Jew not to report abuse but does not threaten that person, “there is nothing I can do about that.”

Zwiebel acknowledged tensions between secular legal requirements and Jewish law. But he said the community was duty-bound to follow the rulings of rabbinic leaders.

Central to the issue for the Aguda is mesirah, the prohibition in Jewish law against informing on a fellow Jew to the authorities. This religious principle flourished in Eastern Europe in centuries past, when many Jews lived in insular enclaves under often hostile governments. But Zwiebel said the notion that mesirah doesn’t apply in modern-day democracies, where there is a fair criminal justice system, is “a minority view” among top rabbis in the ultra-Orthodox world. “The majority view is, there is a prohibition against mesirah,” Zwiebel said.

In contrast, Modern Orthodox rabbis now hold that in cases of child sexual abuse, mesirah does not obligate an alleged victim to obtain permission from a rabbi before going to police. More recently, the Crown Heights Rabbinical Board, a Brooklyn branch of the Chabad Hasidic movement, issued a similar ruling.

Zwiebel, whose group represents ultra-traditionalists, believes that the Aguda made progress when it announced last year that reporting a Jew for sexual abuse did not constitute mesirah as long as reasonable suspicion for the allegations had, in a rabbi’s judgment, been attained. The Aguda position, as laid out then, was that a person who had personally suffered or witnessed abuse could report directly to the authorities. For others, the hurdle posed by mesirah remained.

Zwiebel seemed genuinely distressed that such a stance has now led his organization to be “portrayed as being in the camp of molester protectors.” Yet he and his director of communications, Rabbi Avi Shafran, peppered the hour-long interview with references to the damage that could be done by a false allegation.

Fetching a manila folder from his desk, Zwiebel read in Hebrew from an edict issued last year by Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, a widely revered talmudic authority based in Israel.

In the excerpt, the 102-year-old Elyashiv warned that a “bitter” student could wrongly accuse a teacher of abuse, putting that teacher in “a situation where he would rather be dead than alive.”

Asked how a rabbi could ascertain whether a child is lying, Shafran said, “There are certain subtle [signs] in a child that show whether the child is fantasizing.” He said these indicators included a child’s tone of voice or specific things he or she says.

Offering the hypothetical example of a parent who came to a rabbi after his child told him she had been abused by a teacher, Zwiebel said the rabbi’s decision on whether the parent can go to law enforcement “depends on whether your child has the habit of fantasizing. It depends on whether your child and the teacher have had run-ins in the past. It may require some level of nuance and investigation [by a rabbi] that go beyond the mere allegation.”

Zwiebel said that concerned ultra-Orthodox parents could consult their own rabbi, who, if not experienced in dealing with abuse cases, could find another rabbi equipped to help. The consulting rabbi could, if necessary, also turn to a mental health professional or a social worker to assess the claims, Zwiebel said.

Under New York State Law, social workers and mental health therapists are classified as so-called “mandated reporters,” with an absolute legal obligation to report to law enforcement authorities when they suspect child abuse may have occurred. But Zwiebel has stated that mandated reporters who are members of the Orthodox community are also not exempt from obtaining rabbinic permission first.

Zwiebel said the rabbinic imperative to assess claims before reporting them to police was similar to what he characterized as a requirement for teachers and therapists to establish “reasonable suspicion” before reporting a case to law enforcement under New York’s mandatory reporting laws.

But state guidelines issued pursuant to those laws set the bar much lower. A mandated reporter does not even need a child’s claim of abuse to go to the police. “Your suspicion can be as simple as distrusting an explanation for an injury,” one of the guidelines states.

Asked whether there are any circumstances under which a person should not report a child’s allegation of abuse, Hynes’s spokesman, Jerry Schmetterer, said: “It should be reported to authorities for investigation.”

Zwiebel acknowledged that such rabbinic involvement could cause friction with law enforcement.

“You may have some cases where it’s going to take some time” to assess whether there is reasonable suspicion, Zwiebel said, “and the DA won’t be happy” because of the delay. Or there may be cases, he said, where a rabbi makes “the wrong call” and is prosecuted.

Zwiebel said that if such a position damages the community’s relationship with such leaders as Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who was among those criticizing this policy after the Times’ reports, “oh, well.”

Tapping the manila folder containing the rabbinic pronouncements on sex abuse, Zwiebel said the Aguda’s first loyalty is to “the weight of rabbinic authority in the world today.”

Contact Paul Berger at [email protected] or on Twitter @pdberger

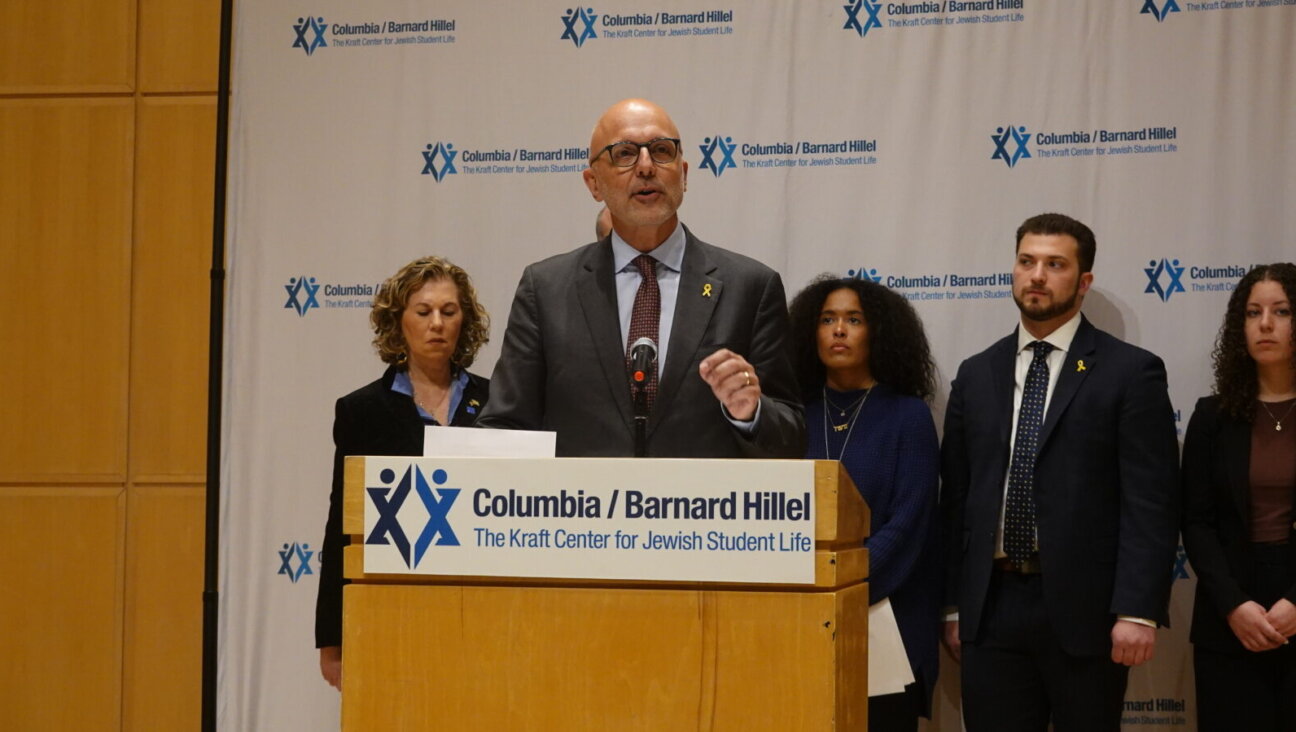

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30