Adelson’s Ethics

Image by getty images

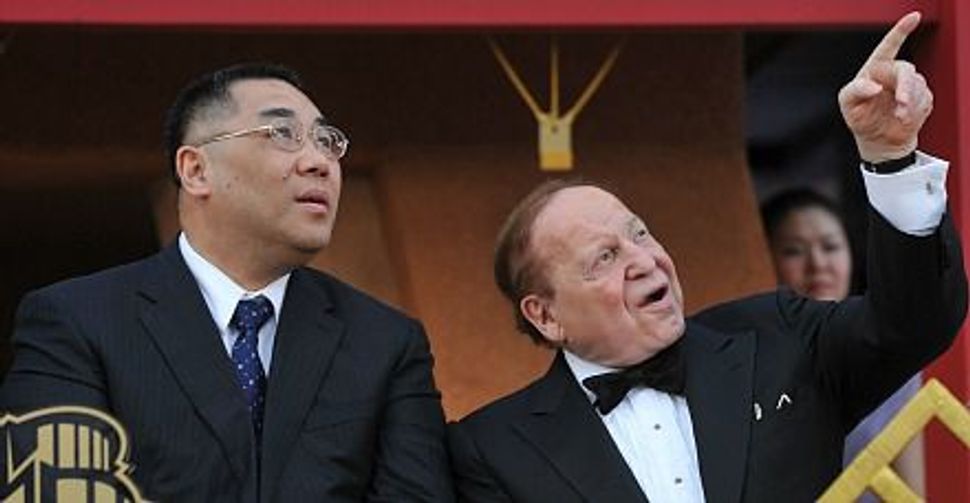

Writing on The New York Times website, Thomas B. Edsall, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, pointed to the possible religious ramifications of the political and financial relationship between Mitt Romney and his most generous backer, casino mogul Sheldon Adelson.

“The source of Adelson’s huge campaign contributions would appear to create a conflict with Romney’s Mormon convictions,” Edsall wrote. “The official website of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints states: ‘The Church opposes gambling in any form, including government-sponsored lotteries.’”

The reasons for such opposition are clearly laid out in an unofficial Mormon website that Edsall quotes: Gambling “undermines the value of work and motivates one to think that they can get something for nothing.” It is considered by Mormons to be a destructive, addictive behavior that inevitably “leads one away from righteousness and into the hands of Satan.”

Since Adelson is not only a robust supporter of Republican causes and candidates but also the chief philanthropist of many Jewish charities, we wondered whether that same conflict might exist in the Jewish context. The short answer: No. While classical Jewish law certainly frowns upon the professional gambler, who is deemed to be so useless and untrustworthy that he is not allowed to act as a legal witness, it doesn’t share Mormonism’s outright objections to all forms of gambling. You don’t see many synagogues holding bingo nights, true, but that may be because raffling off expensive donated items probably raises more cash.

And Adelson is hardly the first Jew to make a killing (financial or otherwise) in what must be Satan’s favorite American vacation destination, Las Vegas.

Much as some in the Jewish community, especially those on the political left, fulminate over Adelson’s fortune and the way he has openly pledged to use it to defeat President Obama, the very fact that it was amassed largely through his global empire of gambling enterprises isn’t, in and of itself, ethically problematic. Jews aren’t Mormons, and he hasn’t been convicted of breaking any laws.

But it is fair to question the business practices that led him to an estimated net worth of $25 billion and the 14th spot on Forbes’s list of the richest people in the world. As Adelson’s political profile has grown — he’s the largest contributor by a long stretch to the Romney campaign and its subsidiaries — those practices have come under heightened scrutiny, as they should.

Adelson and his company, the Las Vegas Sands Corp., have acknowledged that they are currently under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Department of Justice on allegations of foreign bribery. Reporting by ProPublica and other journalists has pointed to the role of Leonel Alves, a legislator and lawyer in Macau who was hired as an outside counsel to Las Vegas Sands. Emails posted by ProPublica show that Adelson’s legal advisers were concerned that large payments of cash to Alves could violate the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Adelson and his company have denied that they have done anything wrong.

There certainly are other troubling aspects to Adelson’s business practices. He is virulently against unions and organized labor, a position he had championed in Nevada. And his company can make what may seem like outlandish demands on local governments in return for the employment and economic boost offered by his casinos.

Consider what’s happening now in Spain, where Madrid and Barcelona are vying to be the site of a new Las Vegas Sands resort that reportedly will host 36,000 hotel rooms, 18,000 slot machines and three golf courses. The Spanish press says that the company has requested that labor laws be relaxed, that rules designed to combat money-laundering be eased, that it be freed from paying Social Security and all taxes for its first two years of its existence, and that visa restrictions be eliminated for foreign employees. Oh, and that Spain’s ban on smoking in public places be lifted.

For a nation mired in deep recession and burdened by double digit unemployment, there’s little wonder why Spanish officials are eagerly courting this multibillion dollar project, despite the demands. The president of Madrid’s regional council has even pledged to try and overturn the smoking ban if that would help her city’s case.

Whether practices such as these comport with Jewish values is, in the end, an individual judgment. Presidential campaigns have long been a magnet for big money accumulated in somewhat questionable ways. (Think of the bootlegger Joe Kennedy and how he helped his son become president.) What’s different this year is the highly accelerated pace of spending spurred on by the disastrous Citizens United decision, and the legitimate civic fear that a very few, very wealthy individuals, Adelson among them, may determine not only the election outcome, but the shape of policy in the next administration.

At the end of his piece, Edsall wrote: “At a minimum, Romney could tell us how he reconciles the values he says he stands for with the basis on which Adelson’s fortune is built.” For us, the question goes even deeper: How can we reconcile the values of a participatory democracy with an election system that grants such an obscene amount of power to the very rich, no matter how their money was made?