Remembrance of Jews’ Past

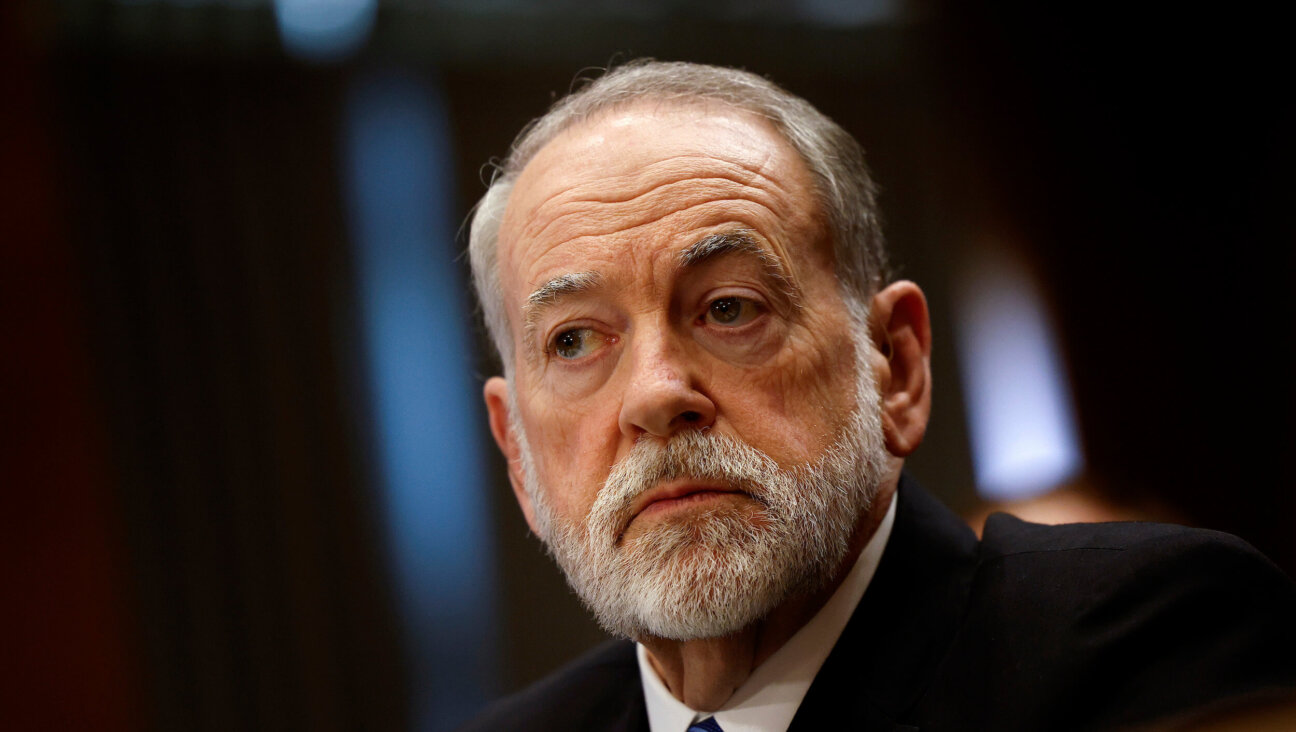

Speak, Memory: One of our most prolific and profound writers on Jewish history, Yosef Yerushalmi died in 2009. Image by Courtesy The Jewish Museum

It was 30 years ago that Yosef Yerushalmi’s” Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory” was first published. The shortest book by Yerushalmi, a prolific professor of Jewish history at Columbia University until his death in 2009, it has had the longest reach. The issues raised in the book, Yerushalmi suggested, are not “necessarily confined to Jewish history.”

He was right. With the new school year beginning, teachers and parents should recall the reason that a book devoted to “zakhor,” or the Jewish injunction to remember, resonates in fields far beyond Yerushalmi’s original subject.

Yerushalmi’s reflections begin with a paradox: For a people so preoccupied by the past, Jews were remarkably indifferent to history. This is odd: After all, as Philip Roth once remarked, “Jews are to history what Eskimos are to snow.” In the vast sea of Jewish history, God is both wave and particle. Nowhere else is the command to remember — zakhor — so present.

And yet something funny happened to the Jews on their way to the past: They got hung up at the destruction of the Second Temple. That cataclysmic event ended history for the Jews — or, more precisely, it ended their curiosity about the past. After 70 C.E., Yerushalmi wryly observes, Jews had all the history they needed. Every subsequent event, invariably grim or bloody, was a mere footnote to everything up to 70 C.E. The story, in short, had been told once and for all. Rabbis, not historians, simply poured current events into the mold provided by the Bible.

European Jewry’s selective recollection of elements of the past, or what we call memory, utterly eclipsed history — the name we give to our critical understanding of the past. The darkness would last for more than a millennium, until history re-emerged on the occasion of another disaster: Spain’s expulsion of the Jews in 1492. The magnitude of this event, which effectively emptied Western Europe of Jews, dwarfed earlier pogroms and expulsions. A handful of diasporic Jews launched a historical inquiry into the past. This, they thought, would help explain if not why, at least how the catastrophe came to pass. But Isaac Luria, founder of Kabbalah, outclassed the historians. A mere history book simply could not compete with the “Book of Splendors.”

Yerushalmi appreciated the irony of his own situation: As a Jewish historian, he worked in a profession that until fairly recently had been alien to the Jewish tradition. Only in the modern era, he wrote, do we find “a Jewish historiography divorced from Jewish collective memory and, in crucial respects, thoroughly at odds with it.” But is this situation specific to Jewish historians? Or, instead, do all history teachers and professors increasingly share their plight?

We are all Jews, it turns out. Historians confront powerful groups attached to their unchanging and particular memory of the past. Perhaps the best-known instance was the battle over the Enola Gay exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum in 1994, when administrators quickly found themselves dashing for cover in a fierce controversy pitting historians against war veteran groups. In a frequently quoted remark, one of the museum’s curators, Tom Crouch, explained the stakes involved: “Do you want to do an exhibition intended to make veterans feel good, or do you want to do an exhibition that will lead our visitors to think about the consequences of the atomic bombing of Japan? Frankly, I don’t think we can do both.”

Indeed, the museum discovered that Crouch was right. An exhibit that was supposed to include both a school lunch box from Hiroshima containing carbonized rice and peas and the fuselage of the plane that created this “artifact” was too great an outrage to the American memory of the war — no matter how carefully these objects were contextualized. Confronted by a largely hostile press, veterans groups and a new Republican majority in Congress, the Smithsonian beat a rapid retreat.

This turn of events appalled most professional historians, who found themselves isolated and largely ignored. But it may well be that our profession was wrong to ignore the great emotional and psychological stakes involved. There is a vast difference between a monograph and a museum exhibit, after all. We, too, must learn from history. First, we must acknowledge not just the reality, but also the legitimacy of collective memory. The emotional bonds of memory cannot be broken by rational and balanced inquiry.

Nor should they be. The “mystic chords of memory,” as Abraham Lincoln recognized, have a deep and genuine claim to our hearts. They shape our sense of who we are and where we need to go as a people. The task of historians is to assist in what Lincoln, in that same inaugural address, declared to be the duty of all Americans: “to think calmly and well” about the subjects that have so deeply polarized our nation.

It often appears that the one place we can “think well” is in the quiet halls of the academy. But these halls are quiet because few laymen ever visit them, and even fewer care what takes place in them. As a result, historians must broaden the conversation beyond our classrooms to extend to our communities. If we fail, we will concede the past to those content to invoke memory alone. And then, we will better understand Yerushalmi’s warning that our choice “is not whether or not to have a past, but rather — what kind of past shall one have.”

Robert Zaretsky is a professor of history at The Honors College at the University of Houston and is the author of “Albert Camus: Elements of a Life” (Cornell University Press, 2010).