Yeshiva U. Rabbi George Finkelstein Acted Inappropriately Even After Ouster

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

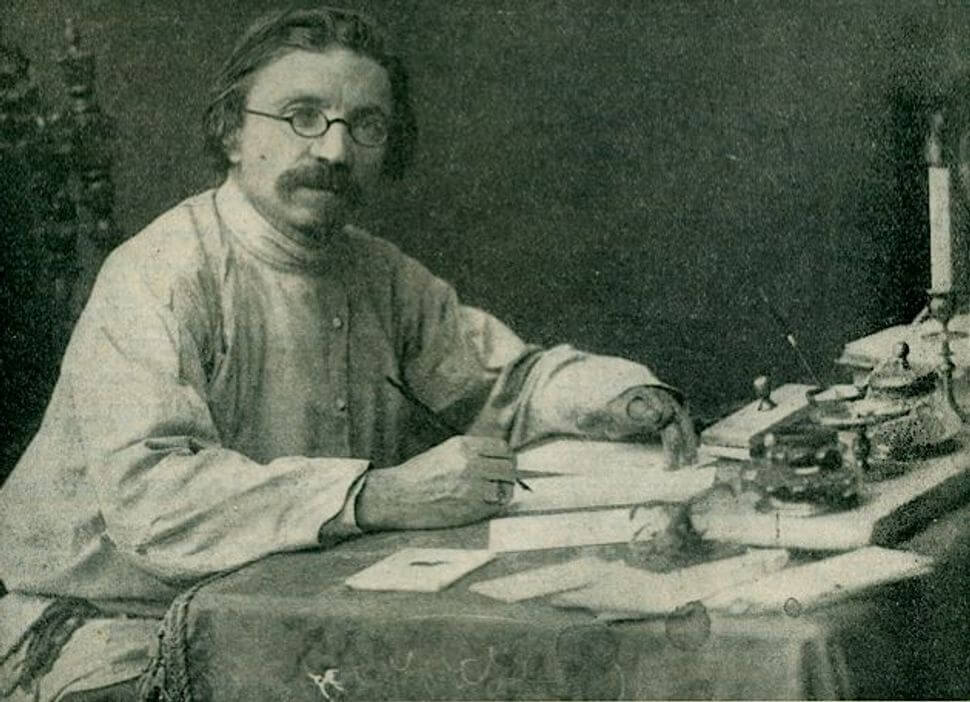

Rabbi George Finkelstein was quietly forced out of Yeshiva University High School for Boys in 1995 because of inappropriate wrestling with students that some of them considered abusive.

But the Forward has learned that the wrestling did not stop after his departure from Y.U. It continued during Finkelstein’s next two posts, as dean of a Jewish school in Florida and as director general of the Jerusalem Great Synagogue in Israel, where he worked until abruptly resigning this past December.

The most recent wrestling incidents documented by the Forward were in 2009.

Finkelstein, 67, has been a respected figure in the Modern Orthodox community for decades, first as an administrator at Y.U.’s high school in Manhattan and later at the Jerusalem Great Synagogue. But allegations that he behaved inappropriately with boys have trailed him for at least 30 years, according to dozens of interviews with former students, colleagues and peers in the United States.

Although former students of Y.U.’s high school long complained about Finkelstein’s behavior to staff members and administrators — both while he worked at the school and after he left — Y.U. appears never to have reported the complaints to police. Nor did Y.U. open an investigation until December 2012, when the Forward published allegations that Finkelstein and another former Y.U. staff member, Rabbi Macy Gordon, had sexually, emotionally and physically abused students over decades. Finkelstein and Gordon deny the abuse charges.

The Forward’s initial reporting concerned Finkelstein’s behavior before he left New York in 1995 for an administrative position at the Samuel Scheck Hillel Community Day School in North Miami Beach. But a former student at that school, who requested anonymity, has now told the Forward that Finkelstein wrestled with him around 1999. The former student said Finkelstein initiated the wrestling one Shabbat when the boy, then about 14 or 15 years old, slept over at Finkelstein’s home.

The Forward has also learned that a young man filed a complaint against Finkelstein with the Jerusalem police in 2009. The man, then aged 26, reported that Finkelstein had taken advantage of his vulnerability — he had serious family problems — and that Finkelstein used his prestigious post at the Jerusalem Great Synagogue to gain his trust. The wrestling took place over two-and-a-half years, in Finkelstein’s home and inside the Great Synagogue.

“Rabbi Gedalia [George Finkelstein] began to wrestle me and told me he is doing it in order to strengthen me and develop my self-confidence,” the man said in a 2009 police statement obtained by the Forward and translated from Hebrew into English.

“I remember one time in particular when he hugged me against my will, about a year ago at his home, and pulled me close to him and I was completely passive,” the statement continued.

“[Finkelstein] pushed me to the floor and I was on my knees facing the floor and he was behind me with his chest on my back. He put his body very close to mine and I think he could not get any closer than that.”

“I think he enjoyed it,” the man continued. “He was breathing heavily and I said to him ‘enough, what are you doing?’ and he stood up and I felt very angry and sexually abused.”

Israeli police dropped the case because of insufficient evidence, according to a letter sent by police to the man in 2010.

Finkelstein did not respond to several requests for comment.

More than one dozen former students who attended the Y.U.-run high school during the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s have told the Forward that Finkelstein had emotionally or physically abused them.

Finkelstein would try to wrestle with students in a Y.U. school office or at his home. Several students said Finkelstein told them that he loved them and that they could feel his erect penis rub up against them while they were pinned to the floor.

In a December interview, Rabbi Norman Lamm, the former president of Yeshiva University, told the Forward that during his tenure — from 1976 to 2003 — he dealt with allegations of “improper sexual activity” against staff members by quietly allowing them to leave and to find jobs elsewhere.

Lamm, a revered figure in Modern Orthodoxy and the current chancellor of Y.U., told the Forward that Finkelstein was forced out of the high school because of the wrestling. “He knew we were going to ask him to leave,” Lamm said.

Lamm said that Y.U. did not inform the Florida school about Finkelstein’s wrestling because “the responsibility of a school in hiring someone is to check with the previous job. No one checked with me about George.” Reached at his home on February 25, Lamm declined to respond to allegations that there were subsequent wrestling incidents after Finkelstein left Y.U.

Y.U.’s knowledge of Finkelstein’s problematic behavior did not stop the school from honoring him upon his departure. At Y.U.’s annual tribute dinner, held in March 1995 at the New York Hilton hotel in Manhattan, Lamm presented Finkelstein and his wife, Fredda, with the Heritage Award “for 25 years of dedicated service.”

Asked why Y.U. honored Finkelstein despite forcing him out because of the wrestling, a Y.U. spokesman said: “As you are aware, everything is being independently investigated by outside counsel who will make their report when the investigation is fully finished.” The spokesman did not respond to a request for details about how the investigation is proceeding and when it might be complete.

Finkelstein took up his post at the Hillel school in Florida in 1995. Many former students and school officials in Florida, including staff and board members, remember Finkelstein as a positive influence. “We had no difficulties with Rabbi Finkelstein whatsoever,” said Martin Hoffman, president of the Hillel board when Finkelstein was hired.

Samuel Maya, 30, a former Hillel student, said Finkelstein was “an incredible person and one of the kindest men I have ever met in my entire life. I have a lot of friends that spent a lot of time with him and never once did I hear one complaint about him,” Maya added.

Another former student, Elie Yudewitz, said that he spent a lot of time at Finkelstein’s home in North Miami Beach and he never saw or heard of Finkelstein wrestling. However, Yudewitz said that rumors about Finkelstein wrestling with boys in New York began to trickle down from former Y.U. high school students to Florida during the late 1990s.

A former Hillel staff member, who requested anonymity, said: “The kids went to convention or camp and they met kids from Y.U. and they asked, ‘Did Finkelstein touch you already?’”

Yudewitz and Maya said Finkelstein often invited boys to stay over at his house during Shabbat. Such behavior was typical for a Jewish educator trying to persuade students to become more observant.

It was during one such sleepover that one former Hillel student said Finkelstein asked him to wrestle.

Even before then, the former student recalled, Finkelstein had taken a particular interest in him. Finkelstein often told the boy that he loved him and, when he called him into his school office, he hugged him “a little bit closer than a normal person might hug.”

“He would lock his feet together and come in close [with his] legs touching each other and he was flat against me,” the former student said. “I never took it as he felt anything more than affection in a father-son type way,” he added.

The former student said he stayed at Finkelstein’s house many times. Then, one time when the two were alone, Finkelstein asked him to wrestle.

“His demeanor changed and he puts on this face like you would do with a kid if [you were] pretending to be angry,” the former student said. “[He] starts making a fist and says, ‘We’re going to come to blows.’”

“The whole thing ended with my getting pinned to the ground and he’s on top of me and I’m thinking, ‘I don’t know what the hell is going on,’” the former student said. “And he starts tickling me…and he got off [me] and that was the end of it.”

The man said that he felt uncomfortable enough that the next time Finkelstein asked to wrestle he refused. But he said that he remained friendly with Finkelstein.

A few years ago, he discovered a blog where former Y.U. High School students wrote of what they perceived to be the sexual undertones beneath Finkelstein’s wrestling. “It made me furious,” the man said. “I realized if he’s doing this to all these guys he’s either really naive or some kind of predator.”

He sent an email to Finkelstein last year asking him to explain his behavior. Finkelstein wrote back to say that he wanted to talk on the phone, but the man could not bring himself to speak to Finkelstein.

“I technically said yes [to the wrestling] which is why at the time I didn’t think anything about it,” the man said. “It’s only as I got older and thought of [the incident again] that I thought about it in a new light.”

In 2001, a former student from Y.U.’s high school, Simeon Weber, warned the Florida school that Finkelstein liked to wrestle with boys. He persuaded two prominent New York rabbis to corroborate to Hillel administrators his own story of wrestling with Finkelstein. Finkelstein left the school the same year.

When the Forward tried to contact the Hillel school in December, the school’s chief operating officer, Rafael Quintero, did not return multiple calls and emails for comment.

On February 20, the Forward sent an email to Quintero and to other Hillel officials alerting them to the 1999 incident involving their former student. The email asked what, if anything, the Hillel school had done to investigate Finkelstein’s employment at the school and to ascertain whether students were harmed.

No one responded to the email or to subsequent calls to Quintero and head of school, Rabbi Pinchos Hecht.

Allegations of Finkelstein’s inappropriate behavior preceded him when he applied for the job of director general of Jerusalem’s Great Synagogue, in 2001.

The Great Synagogue was concerned enough that its board launched an investigation and was twice reassured by a Y.U. “authority” that the rumors were baseless, according to Zev Lanton, the synagogue’s director general. Lanton told the Forward in December that after seeking legal advice the synagogue could not reveal the name of the Y.U. official who vouched for Finkelstein.

But in a statement released the same month Lanton said: “We would like to emphasize that during the ten years in which Rabbi Finkelstein served the synagogue, there was never any hint, direct or indirect, of any inappropriate behavior on his part.”

Finkelstein did inform the synagogue a few years prior to the statement that he had been summoned by police in Jerusalem regarding “a complaint reiterating the original allegation,” the statement said — apparently referring to allegations that Finkelstein abused a student in New York.

But the police report obtained by the Forward shows that the summons related to a complaint that Finkelstein assaulted a young man over a period of two-and-a-half years in Finkelstein’s home and inside the Great Synagogue.

The man who filed the complaint said he had family problems and few real friends when Finkelstein befriended him after he emigrated from Israel to America in 2005. “I remember [Finkelstein] saying, ‘I can play the role of father for you,’” the man, now 29, recalled in a telephone interview with the Forward.

He said Finkelstein would invite him to his synagogue office mostly when no one else was around. “He would say, ‘I love you. Do you love me?’” the man recalled. “At a certain point he wanted me to hug him. He would always seem to press me too tightly.”

“After hugging me, he would push me,” the man said. “He’s got a big office in a shul with an operating budget of millions of dollars and I’m like, ‘What the hell is going on here?’”

He said that the “bizarre relationship” continued as the “gray-haired” rabbi, now in his 60s, graduated from pushing to “tussling” and then to wrestling. One day, he found himself pinned to the floor in Finkelstein’s Jerusalem home, his face pressed to the ground. “I could feel his [penis] pushing against me,” the man said. “It was such a thin line between a wrestling move and humping someone.”

After contacting the police, the man also opened an anonymous email account and sent an email to the synagogue warning them about Finkelstein. He said that he never received a response.

“These are extremely painful memories, you can’t imagine,” the man said.

Jacob Rowe, a Great Synagogue board member, did not directly address whether the synagogue received an anonymous complaint about Finkelstein. But he said that he never heard “anything but positive” things about Finkelstein. “People who make anonymous things are destroyers of Judaism,” Rowe said. “No one can be protected against anonymous things like this.”

Rowe said Finkelstein still attends the synagogue and is welcomed warmly. “Everybody knows him to be a tzaddik [righteous man] here,” Rowe added.

One year after the police complaint was made, Mordechai Twersky, a former student of Y.U. High School, said he also tried to warn the Great Synagogue board.

Twersky said Finkelstein wrestled him several times in 1980, during his junior year at the school. In February 2010, he attended a meeting in Jerusalem where he met Tobias Berman, an officer of the Great Synagogue.

“Toward the conclusion of the meeting I got into an exchange with Berman, and I mentioned that I was a victim of his shul’s director general,” Twersky said. “Berman said he didn’t believe what I was alleging.” (Berman said he recalled a conversation with Twersky, but not what the conversation was about.)

The following month, Twersky filed a complaint against Finkelstein with Takana, a Jerusalem-based forum made up of educators, rabbis, yeshiva heads, lawyers and therapists who deal with allegations of sexual harassment and abuse made against clergy.

After hearing Twersky’s testimony, Takana met with several members of the Great Synagogue leadership who said they would look into the matter.

Zalli Jaffe, the Great Synagogue’s vice president, said the board took the allegations raised by Takana “very seriously.” But Finkelstein’s denial and the fact that he was able to become principal of the Hillel school after leaving Y.U. were seen as proof that he was innocent.

Jaffe, a commercial lawyer, said the synagogue had always believed the Israeli police investigation and the Takana investigation to be about the same allegation. He said he was surprised at the time that Israeli police would investigate allegations of abuse decades earlier in the U.S., but that he was “stunned” by the Forward’s suggestion that the police investigation referred to allegations of incidents in the synagogue.

He said that the synagogue had “no reason to suspect anything” when Finkelstein was employed at the synagogue, and that if Finkelstein was providing guidance to anyone in Jerusalem it would have been “outside his position” as director general.

Finkelstein retired from his post as director general of the Great Synagogue last summer, slipping into a lesser role of ritual director. He resigned from that post in December after the Forward published its first story detailing allegations against him.

Nathan Jeffay contributed to this story from Jerusalem.

Contact Paul Berger at [email protected] or on Twitter @pdberger