Apparent Suicide of Ex-Hasidic Woman Deb Tambor Sparks Funeral Chaos

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Confusion and controversy marred the funeral of a mother of two said to have committed suicide after leaving her Hasidic community and being denied access to her children.

Friends and family of Deb Tambor, a former resident of the ultra-Orthodox community of New Square, in upstate New York, believe she killed herself on Friday, September 27 in the bedroom of the home she shared in Bridgeton, N.J. with her boyfriend, Abe Weiss. Like Tambor, Weiss is a former member of the Skver Hasidic sect, which founded and controls New Square, a village about 50 miles north of New York City.

Despite their close relationships with Tambor, Weiss and some 40 former ultra-Orthodox friends of hers who quietly converged on New Square Sept. 29 to witness her funeral and pay tribute to one of their own were unable to do so. Members of the New Square community said that Tambor’s family chose to bury her elsewhere with only immediate family present due to the shame she had brought upon the family and the community.

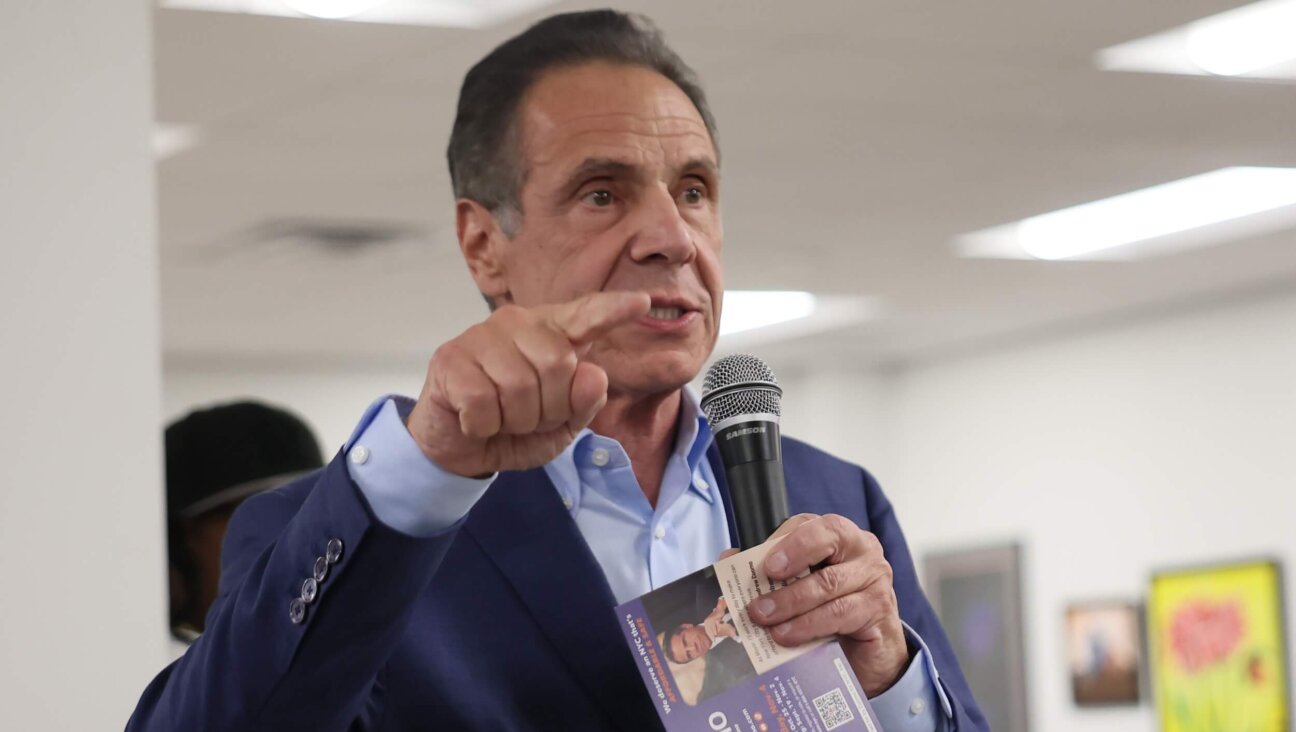

Deb Tambor and Abe Weiss

“Who wants to be buried next to this lady?” New Square resident Menashe Lustig told the Forward in a phone interview. “It’s very difficult to know where to put her. I hear they called up the rabbonim in Israel and they told them the decision” that she should be buried elsewhere. Of Tambor’s life and death, he said, “The family is ashamed. They’re very ashamed.”

New Square, which was established by the Skver Hasidic group’s then-grand rabbi, Yaakov Yosef Twersky, in 1954, is considered one of the most culturally isolated towns in America, with sex-segregated streets and female residents who, in obedience to the town’s rabbis, do not drive.

The official cause of Tambor’s death remain undetermined, pending findings from the Cumberland County, N.J., coroner. Weiss told the Forward he rushed home from work in the early afternoon on the day of her death, concerned because he had not heard from her in the morning as usual. He found her lying on the floor of their bedroom, he said, next to two empty pill bottles and a half-empty bottle of alchohol, and immediately called 911. Police confirmed finding her body when they responded to the call.

An official with New Jersey’s Office of the Attorney General said toxicology tests can take 12 to 16 weeks to receive. Neither Tambor’s friends nor her family suspect foul play.

According to her friends, Tambor became depressed after leaving the New Square community four years ago and divorcing her husband. Weiss, her live-in boyfriend, said her family had disavowed her earlier, when she told family members that she had been sexually abused by a member of the tight-knit New Square community as a child and they denied it.

Driven by her depression, Tambor checked herself into a psychiatric hospital, said Weiss, which is when family members in New Square moved to block her from seeing her children, who are now 11 and 13.

“Her depression started when she decided to leave the community and was threatened with losing her kids,” Weiss told The Forward. “Her biggest issue was that no one cared for her, everyone blew off all her issues.”

Weiss and other ex-Orthodox friends of Tambor began congregating about 4 p.m. Sunday for her funeral outside New Square’s funeral home, located on a cul de sac at the end of Roosevelt Avenue. According to some of those who gathered, every few minutes a Skver Hasid would slowly drive past them.

Weiss said that the crowd of formerly Orthodox friends were given a variety of conflicting reports by their contacts inside the community: that the funeral would be in an hour, or before dark, or after night fell, or at midnight. Rumors flew back and forth by text and in a closed Facebook group for Jews who are “off the derech [path], or OTD, as many former ultra-Orthodox Jews refer to themselves.

Around 9 p.m. one of Tambor’s uncles came to the group and said he would call the police and have them all handcuffed, Weiss said. The police came, stayed about 30 minutes and then left, saying that the friends had a right to be there, said Weiss and others who were present.

At 4 a.m., still uncertain when Tambor’s funeral would actually take place, her friends stood in a circle in front of the funeral home and lit candles. A few friends spoke about Tambor. They then observed a moment of silence before dispersing.

Five minutes later, while Weiss was en route to stay with a friend in nearby Monsey, N.Y., one of Tambor’s brothers texted him offering to take him to view her body, Weiss related. Two brothers picked him up and took him to a quiet street just outside New Square’s border, where a privately owned minivan waited. In the back of the van was Tambor’s coffin, Weiss said. Her brothers allowed him to look but not touch the coffin or take off the top so that he could see her face.

Later that morning, at around 10 a.m. the same brother texted him that Tambor’s funeral was taking place at that moment at a cemetery in West Babylon, Long Island, Weiss said.

“It was nice what they did yesterday. It would have been nicer if they let me come to the funeral,” Weiss said.

A member of Tambor’s family told the Forward that the decision not to bury Tambor in New Square’s cemetery was not because she was a suicide. Suicide is considered a grave violation of Jewish religious law, and traditional practice formally prohibits suicides from being buried within the gates of a Jewish cemetery. But other suicides have been buried in the community cemetery, said the family member, based on the presumption that they repent in their last breath. The family member spoke only on condition of anonymity due to fear of retribution from his community were he to be quoted by name.

The head of the New Square burial society, Yaacov Byer, declined to answer any questions about Tambor’s funeral.

Lustig said she was buried far away because she had strayed from religion. “In public they say it’s because she wasn’t shomer Shabbos [Sabbath observant]. But my friend told me it was because she has relations with strangers and everything. It’s like she was free.”