Papa Was a Rolling Stone How One Young Woman Pieced Together Her Father’s Story

Assembling My Father

By Anna Cypra Oliver

Houghton Mifflin, 368 pages, $25.

* * *|

The old chestnut about 1960s hedonism ran that if you remembered the decade, you weren’t really there. If the joke once reflected a popular perception of the times, it also missed a much more unpleasant truth. Released from social conventions, unmoored from relationships that gave their lives context and meaning, some found themselves living a life for which they seemed ill prepared, as several recent documentaries (“Weather Underground”) and novels (“American Pastoral”) have been quick to point out. Add to this list Anna Cypra Oliver’s “Assembling My Father,” an unusual, well written and at times gripping account of an oddly emblematic casualty from a decade in which many lost their way.

By all accounts, Lewis Weinberger was a cocky, sophisticated teenager who yearned for adventure — whether prowling New York City’s avant-garde museums and jazz clubs, or trudging through postwar Europe. As an undergraduate during the late 1950s, he put his love for history and art to good use as a star contestant on the TV quiz show “GE Bowl.” A decade later, living with his wife and children in Florida, he helped design a stunning modernist house that merited attention in national magazines and papers.

Yet it didn’t escape those closest to him that beneath Lewis’s intellectual swagger lay a wounded spirit who felt abandoned by his parents and eager to replicate the triumphs of his older brother. Whatever his psychological makeup, he seemed unable to withstand a string of destabilizing events, including the death of his parents, a bankruptcy and, most significantly, his separation and divorce from Anna’s mother, Teresa. Eventually finding himself adrift in New Mexico — he and Teresa had moved out west to live off the land, settling into a ramshackle cabin sometime in the early 1970s — Lewis killed himself in 1974, at age 35. His daughter was 5.

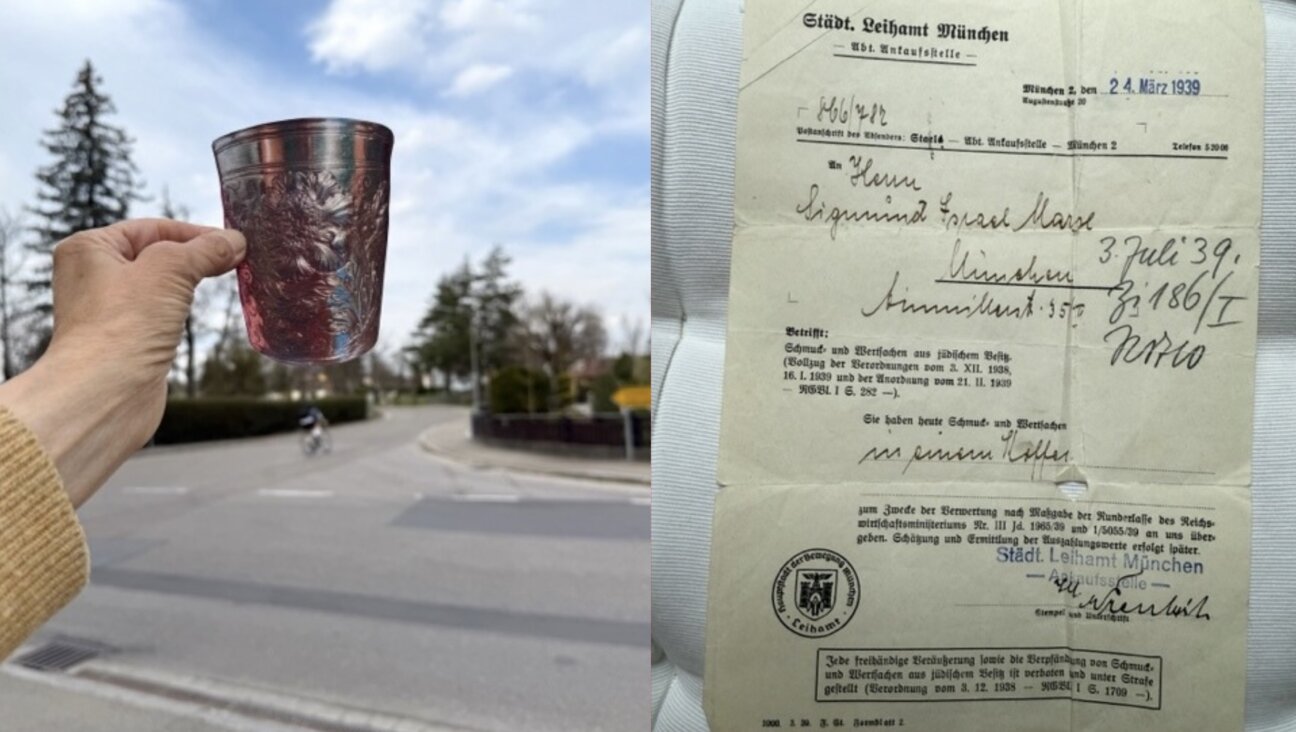

Not surprisingly, this act overshadowed what little else Anna Cypra Oliver knew about her father. But in her mid-20s, Oliver — herself adrift from an unhappy marriage as well as from the fundamentalist Christian faith in which she was raised — felt compelled to discover the man hidden behind the family lore and half-remembered anecdotes. Recounting such discoveries as a trunk filled with Lewis’s photographs, the journal from his last years, reminiscences of friends and family, even a tape of his voice, Oliver begins to decipher a life she barely remembers. “I relish the way my father is taking shape in my hands,” she writes. “I feel as if I’m putting Humpty Dumpty back together again.”

At first glance, “Assembling My Father” recalls a long tradition of father-daughter memoirs in Jewish literature, stretching from Anzia Yezierska’s thinly veiled autobiographical “Bread Givers” to Anne Roiphe’s “1185 Park Avenue” and beyond. But in several key ways — not least because the men at the center of their attention share the same profession — this memoir reminded me not of a book but of a film.

In his 2003 documentary “My Architect,” filmmaker Nathaniel Kahn, son of the legendary Louis I. Kahn, pieces together the story of a father he barely knew (Kahn died of a heart attack in the men’s room of New York City’s Penn Station in 1974, when Nathaniel was 11). Like the film, “Assembling My Father” features a highly inventive visual format, a patchwork of narratives, e-mails, photographs, even scribbles of arithmetic from Lewis’s journal

reproduced in the margins of the book. And while you can’t compare the two subjects — one man left a public legacy of world-class buildings, the other a few boxes and photographs — both works share a willingness to wrestle with the pain of absence until a nuanced if unflattering portrait of their subject emerges.

For all this talk of absent and reassembled men, the most intriguing character in the memoir might well be not Oliver’s father, but her mother. After leaving her first husband, Teresa Oliver married a string of alcoholic, sometimes abusive, men, raising Anna and her older brother in an old house without electricity or running water. In the wake of Lewis’s suicide and her own domestic problems, Teresa sought refuge amid other broken souls in a local Pentecostal church.

How a beautiful, artistic, well-to-do Jewish girl became, by turns, a hippie and still later a fundamentalist Christian makes for a fascinating chapter in the story of postwar Jewish identity. Because she lacks self-awareness, at least in this telling, Teresa seems unable to explain her life choices — something that’s left for her daughter to untangle. In this way, Teresa remains something of an accidental marrano, her Jewish identity as well as her own deepest impulses hidden even from herself.

In the end, “Assembling My Father” is as much an intellectual and spiritual autobiography as it is the story of Oliver’s parents. Many of the book’s early sections are devoted to Oliver’s wavering commitment to the church and her first marriage, while the later ones chart her transformation as she moves to New York, reclaiming her father’s severed connection to Judaism in the process.

If, at times, her concept of Yiddishkeit seems a trifle pat or unexamined (“the Jews I know are highly literate, liberal-minded people who feel linked to other Jews through a common culture and a common history, especially the Holocaust and anti-Semitism”), it’s a testament to Oliver’s strength as both a person and a writer that she remains committed to her search, no matter what she turns up or how it changes her life. One of the few triumphs in this frequently tragic story is that the man who was unable to find his own way provides something of a path for his daughter.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 3

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

- 4

Opinion I first met Netanyahu in 1988. Here’s how he became the most destructive leader in Israel’s history.

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture I have seen the future of America — in a pastrami sandwich in Queens

-

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

-

Opinion Gaza and Trump have left the Jewish community at war with itself — and me with a bad case of alienation

-

Fast Forward Trump administration restores student visas, but impact on pro-Palestinian protesters is unclear

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.