The Legacy of a Pope

For those of us who are neither Catholic nor Christian, it was at first startling to witness the worldwide outpouring of emotion that greeted the death of Pope John Paul II. A man dies. His job comes open. A replacement will be chosen. One might expect this to be a time of grieving for those who knew and loved the man, a wrenching period of transition for the institution he headed, even a moment of sadness for those around the world who fell under the sway of his public persona. But what was it, we might have wondered in the last few days, that brought the world virtually to a halt and dominated every front page for an entire week?

It is a question that answers itself. We were reminded this week that we live in a world community that is fully one-third Christian. One billion of the world’s 6 billion people are Roman Catholics, and they lost a father this week. Another billion are Protestant and Orthodox Christians for whom the pope is at least a reminder, at best a symbol of the Christian unity to which they aspire. For those who are not Christian, the pope’s death is a time to ponder the depth of feeling and belief shared by so much of the world.

This pope was much more than just a symbol, however. By the strength of his charisma, his passion and his boundless energy he made himself and his office into an engine — and an embodiment — of religious revival around the world. Billions of believers, Christian and non-Christian, looked to him as the premier voice of moral conscience in our age.

In two areas alone, the pope’s achievement is so vast that his place in history seems assured. He was an uncompromising foe of communist dictatorship in his native Poland and around the world. For many, that opposition to tyranny was his greatest single legacy, a gift that can be shared by all lovers of humanity, whatever their faith.

He was, secondly, a revolutionary force in Catholic-Jewish relations. Like his opposition to communism, his friendship toward Judaism was a personal commitment, rooted in his Polish past and in his moral vision. More than any pope before him, he made Christian-Jewish reconciliation a personal mission and imposed it on his church.

Sadly, these acts are not the whole of his legacy, for John Paul II was, above all, a transformative figure in world religion. Ruling unchallenged for a generation over the world’s largest religious community, he remade the Catholic faith in ways that weakened it as a force for greater social good, turning it into a force of reaction and repression on some important fronts. It may be that this legacy will be his most profound, overshadowing and even undermining his other achievements.

John Paul’s Christianity was a deeply conservative religion of mystery, chastity and obedience. Beyond the enthusiasm and human warmth that he transmitted, his teachings were focused largely on those three themes. His message to his church, and beyond that to the world community, was one of opposition to the social gospel that dominated Christianity for a century before him. He taught reverence for mysteries that are beyond reason, conquest of sexual desire in the service of life, and dedication to the sacraments and hierarchy of his church. If the world now seems a frightening place of unreasoning religious passions, that is partly the legacy of this pope.

In the world of public affairs, his beliefs translated into an activist church that led battles around the world for sexual repressiveness and against reproductive freedom. Longstanding Catholic teachings on peace, democracy and economic justice were pushed to the rear. In the end, John Paul’s opposition to oppression seemed to begin and end with communism.

For Jews, then, this is a week of deeply mixed emotions. We live in the world, and we cannot escape the knowledge that it is a world that was in some ways made narrower and more unreasoning by the gospel of John Paul II. At the same time, his impact on Jewish history is so profoundly good that we may be forgiven for thinking it overshadows the rest.

He broke new ground as a church leader in his expressions of warmth toward Jewish causes, of grief at Jewish suffering and, perhaps most significant, of remorse at the Christian role in Jewish persecution.

He did not begin the revolution. It was Pope John XXIII who launched the millennial doctrinal shift, convening the Vatican council in 1963 that transformed the church’s view of its place in the world and its relations with other faiths, not least Judaism. It was Paul VI who formalized the changes in church structure and teaching, ensuring that they would outlast any one pope or council.

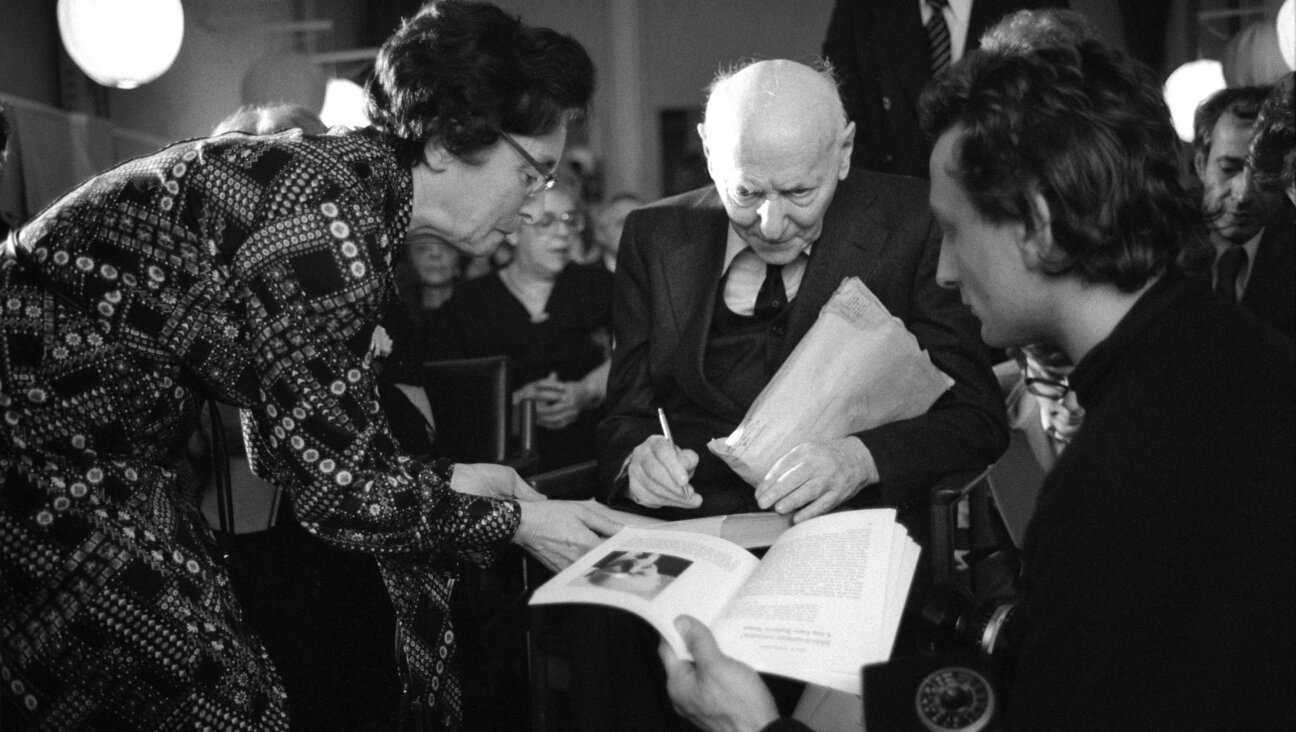

John Paul II was the pope who brought these transformations to the masses, both Jewish and Christian. Because of his long reign, the third longest in papal history, he was present for much of the post-revolution history. Because of his personal commitments, he pushed the process farther and faster than nearly anyone expected. Because of his volubility and charisma, he was able to make the changes come alive for vast audiences on a world stage in the television era. He prayed at Auschwitz. He visited a synagogue. He prayed at the Western Wall.

Perhaps most important, he announced a series of doctrinal innovations that addressed Jewish sensitivities in a profound way. One was recognizing the State of Israel. Another was declaring antisemitism to be a sin.

A third, the most sweeping, was his declaration from the Roman synagogue pulpit in 1986 that the Jews’ covenant with God remains in force. That means, as church leaders have explained over and over since then, that Catholicism now recognizes Judaism, alone among the world’s non-Christian religions, as a pathway to heaven. It means the church no longer aspires to convert Jews to Christianity. This alone justifies all the praise showered on him by Jewish spokespersons this week.

In the end, the magnitude of John Paul’s impact defies simple evaluation. He took the throne of St. Peter out of the Roman curia and placed it at the center of the world stage. Never again will cynical politicians ask how many armies the pope commands.

For those of us who are not Catholic, one more consideration must guide our thoughts. For our Catholic neighbors, the specific achievements of the man pale in comparison to the magnitude of his office. They lost a familiar face, but more important, they lost a beloved pastor. One billion of our fellows are in mourning for a father this week. We share their grief.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

Film & TV In ‘The Rehearsal,’ Nathan Fielder fights the removal of his Holocaust fashion episode

-

Fast Forward AJC, USC Shoah Foundation announce partnership to document antisemitism since World War II

-

Yiddish יצחק באַשעװיסעס מיינונגען וועגן די אַמעריקאַנער ייִדןIsaac Bashevis’ opinion of American Jews

אין זײַנע „פֿאָרווערטס“־אַרטיקלען האָט ער קריטיקירט זייער צוגאַנג צום חורבן און צו ייִדישקײט.

-

Culture In a Haredi Jerusalem neighborhood, doctors’ visits are free, but the wait may cost you

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.