Southern Teachers Hit the Road To Educate Rural Communities

GREENVILLE, Miss.—When Lauren Antler accepted a position with Teach for America, she knew that her two-year assignment would find her teaching in a public school classroom five days a week, likely in a rural location far from her home in New York City.

But when Antler, 23, landed in the Mississippi Delta community of Greenville last year, she didn’t expect to don her teacher’s cap yet another day, volunteering as a Sunday school instructor at the Hebrew Union Temple.

With a rudimentary Jewish background, Antler admits that she was an unlikely candidate to be a Sunday school teacher. But the Reform synagogue was thrilled to have her on board: With her basic knowledge of Hebrew, not only is she a rarity in Greenville, but the young, enthusiastic teacher could help instill a love of Judaism in the eight pupils who attend the one-room school.

“I’ve made a serious commitment to the Sunday school,” Antler said. “I think it’s important for kids growing up here to see someone young and making that choice to be Jewish.”

In the Deep South, Jewish education has long relied on people like Antler who dedicate their spare time to teach ing kids about their heritage. Whether it’s a local physician who doubles as a bar mitzvah tutor, or a rent-a-car agent who teaches religious studies, these are the people keeping Jewish culture alive in the South.

“Small congregation culture is that everyone has to pitch in,” said Debra Kassoff, a former student rabbi in Greenville’s congregation who is currently the rabbinic director of the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute for Southern Jewish Life. “If you want to have a Jewish community, you are the Jewish community. You can’t expect someone else to do it for you.”

Greenville once boasted a Jewish community of some 200 families. Today, with 65 families, it’s still considered among the more fortunate, small Jewish communities in the Deep South — most of which are experiencing a slow, quiet death while communities thrive in major Southern cities like Atlanta and Houston. The steady decline of small-town Southern Jewry — with its only-in-America blend of catfish-meets-gefilte-fish — has seen the near-extinction of Jewish communities in rural towns such as Clarksdale, Miss., and Selma, Ala. In many towns, the “eternal flames” atop synagogues are flickering; an overgrown cemetery or a boarded-up sign for “Goldberg’s Shoes” are all that remain of a Jewish past.

With some 1,500 Jews statewide, Mississippi, with its endless cotton plantations and lack of urban life, has been hardest hit. Sixteen Jewish congregations exist across the state — but only two have full-time rabbis, and most have a shortage of teachers.

Cheryl Katz, a housewife in Madison, Miss., volunteers as the first-grade teacher at Beth Israel in Jackson. “It’s definitely a labor of love,” she said. “Especially living in a place where there aren’t that many Jews, if my children don’t see that it’s important to me, why would it be important to them?”

The unique challenges of educating tiny, isolated Jewish communities were addressed at a conference in Canton, Miss., earlier this month, titled “Teaching Teachers and Those Who Want to Be,” sponsored by the Institute for Southern Jewish Life. It was the first-ever educational conference solely dedicated to this isolated population — and surely one of the rare occasions in which the birkat hamazon, or blessing after a meal, was recited after a feast of fried chicken, pigeon peas and collard greens.

The Southern institute is upgrading what its energetic founder and president Macy Hart — a 55-year-old native of Winona, Miss. — considers a “bold, old” idea. It is sponsoring circuit-riding rabbis and Jewish educators who hit the road, visiting isolated Jewish communities that no longer can afford Jewish professionals leading services, teaching classes and assisting what Hart calls “merchant-by-week, teacher-by weekend” faculty — like Antler — upon whom small Southern congregations have relied for so long.

As the institute’s newly appointed rabbi, Kassoff returned last week from her first weekend “on the road,” a visit with Temple Shalom, a 60-family congregation in Lafayette, La. Over the course of her three-year commitment to the institute, she plans to visit two different congregations throughout the region each month.

Distance, said Kassoff, is the biggest obstacle to the program’s success. “There’s so much potential for bringing people together, making connections and doing regional programming,” she said. “But if its going to take someone four, five hours to get somewhere, that’s really hard. Helping a population that’s really spread out is very challenging.”

At the conference, the four-year-old institute also presented a new curriculum covering Jewish education from kindergarten through 10th grade.

“I’ve been waiting for something like this for so long,” said Sandra Liverman of Wesson, Miss., who has taught at a religious school in Jackson. “I want the kids in this area to have a good Jewish education. I’m obsessed with it.”

Liverman is also concerned about the adults in the community. Nearby Brookhaven, Miss., is home to approximately 10 Jewish adults. Liverman hopes to launch a weekly study session there, using the institute’s curriculum as the basis for adult learning.

Like many of her peers — who are lawyers, corporate middlemen or students themselves — Liverman, a nurse by profession, has had no formal training in Jewish education.

Currently, the institute is piloting its traveling-educator program in four states: Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana and Alabama. Kassoff and two educational fellows are already on board, taking the institute’s new curriculum on the road.

Eventually, Hart hopes to broaden the program to 12 states, with four educators and 18 fellows hitting the road part time in order to assist the underserved Jewish communities in the South. In total, Hart estimates that the project will cost $1.4 million annually.

Education is but one component of Hart’s ambitious plans. He created the institute — an outgrowth of the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience, with one site in Utica, Miss., and the other in Natchez, Miss. — to provide a dizzying array of services to Southern Jews. Once its goal of a $13.6 million endowment is reached, the institute aims to provide local Jews with everything from historic preservation to cultural activities to oral history research and, eventually, a genealogy center.

With its staff of 19, the institute is run with the round-the-clock fervor of a summer camp. Relying on a mostly young staff of interns and fellows, Hart and company work long hours, bringing a sort of mind-body-spirit intensity to their work. Everyone seemingly spends his or her free time together as well.

“We have to overcome a lot of ‘that’ll-never-work’ attitude,” Hart acknowledged. “There has to be an intensity — we have to make believers out of people who believe there’s no future.”

It’s a challenge to make believers out of the region’s largely aged Jewish population — many of whom say that Hart’s plan is brilliant in theory, but will no longer help their nearly dead communities.

But Hart and company are adamant about not neglecting those wanting to involve themselves in an active Jewish life. The program is not about keeping young Jews in the South, Hart stresses. “We’re trying to ensure the Jewish future,” he said. “We want to promote Jewish life so that when they move to the next place, they’re in this whole Jewish life thing.”

An even loftier goal is that Hart hopes to transform the organized Jewish community’s approach toward small-town Jews. “Every single Jewish life counts, whether you’re in El Dorado, Ark., or the former Soviet Union,” Hart said. “I want the Jewish community to think outside their ZIP code.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 4

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

In Case You Missed It

-

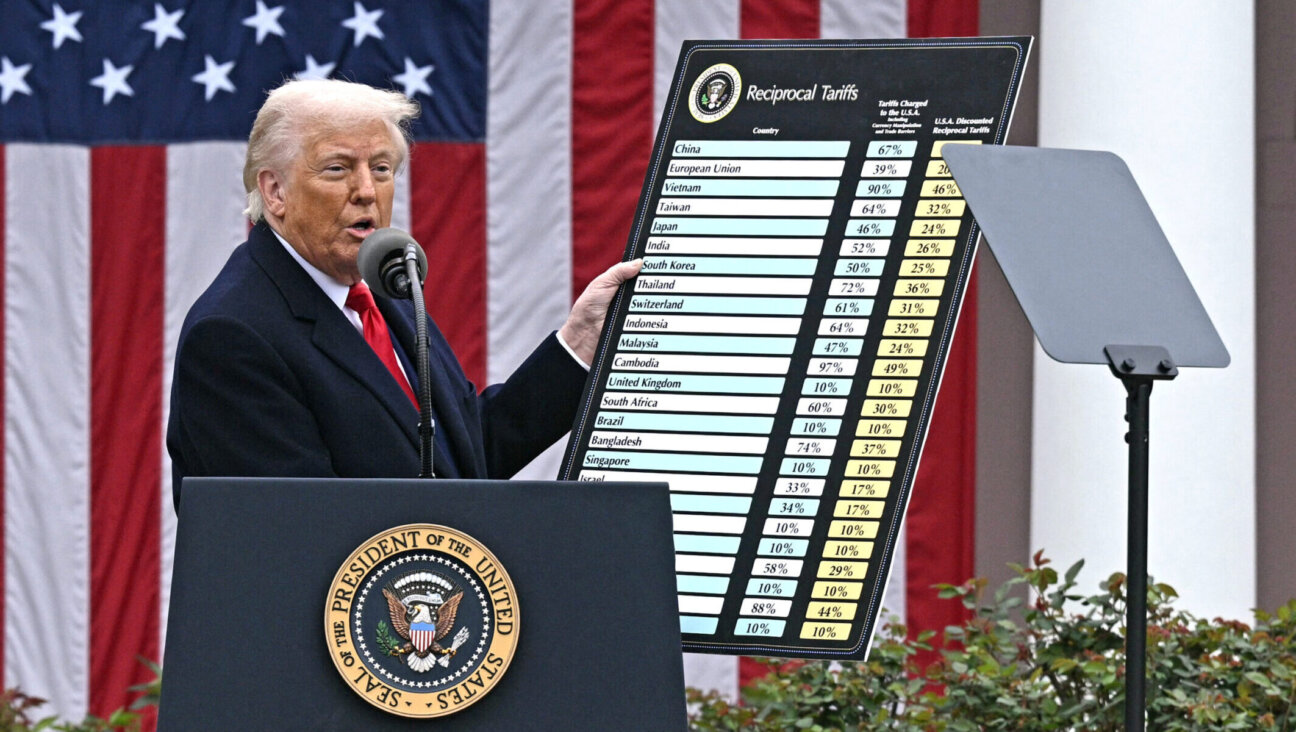

Fast Forward Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ includes 17% tariffs on Israeli imports, even as Israel cancels tariffs on US goods

-

Fast Forward Hillel CEO says he shares ‘concerns’ over campus deportations, calls for due process

-

Fast Forward Jewish Princeton student accused of assault at protest last year is found not guilty

-

News ‘Qatargate’ and the web of huge scandals rocking Israel, explained

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.