Animation, ‘Archer’ and the Art of Offending

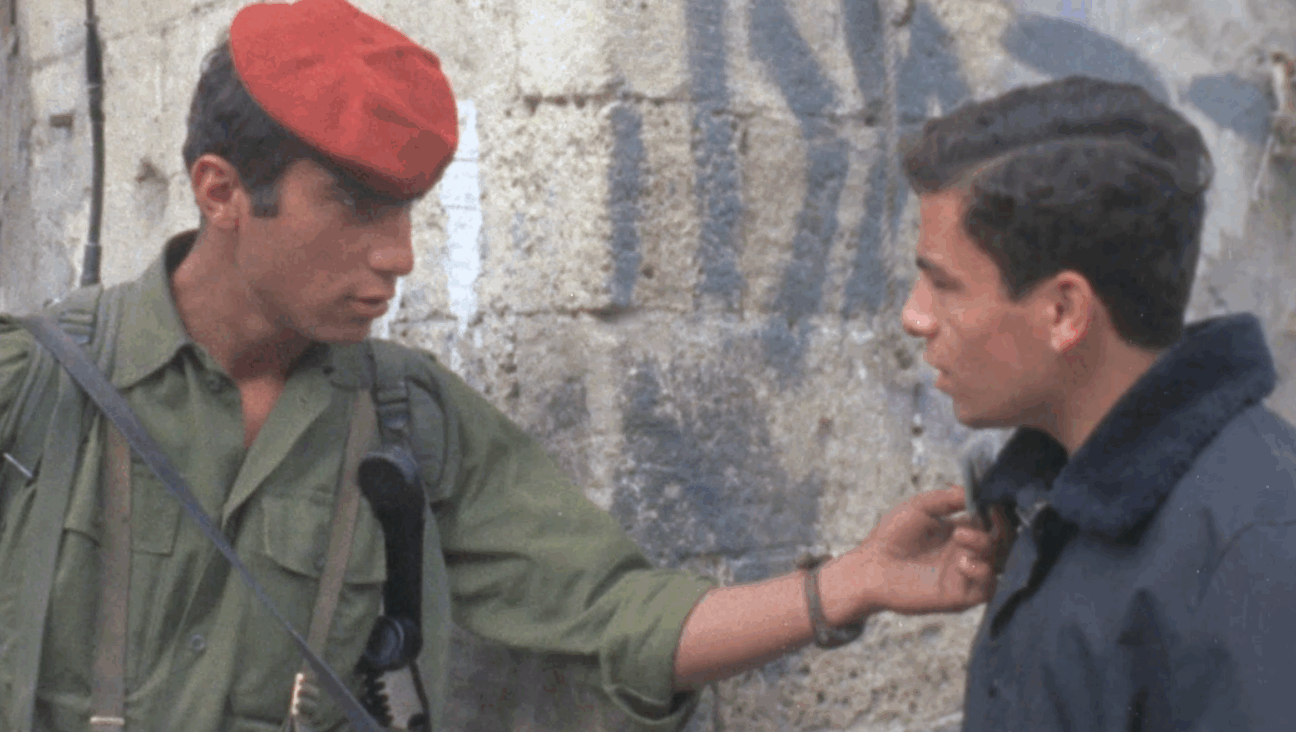

Image by Courtesy of FX

Sign up for Forwarding the News, our essential morning briefing with trusted, nonpartisan news and analysis, curated by senior writer Benyamin Cohen.

At the beginning of the sixth and current season of “Archer,” an animated spy comedy on FX, the title character, a handsome, womanizing secret agent, is sent to the jungle of Borneo to recover the computer from a downed American spy plane. While making his way across the island, Archer runs into a Japanese soldier who has been stranded since the middle of World War II and doesn’t know — or accept — that Japan has lost the war. “Well I hope you’re happy, because I feel like a total dick, and also kind of racist,” Archer says after he subdues the soldier and leads him across the island, bound by the wrists and neck. “And I resent you making me feel like that so…. I’m not a racist.”

Is Archer — or “Archer” — racist? The show is full of indelicate jokes, many of them about race. But the answer, I think, is no. Though the show rampages through identity politics like the cast of “Duck Dynasty” through an Audubon center, the result is liberating, not oppressive. While some comedies might achieve this effect by enabling their viewers to indulge in pent-up racist attitudes, “Archer” skewers both prejudice and the pieties it hides behind. Racism, the show seems to argue, makes a better target when it’s out in the open.

In this sense, “Archer” is hardly new. Adult-oriented cartoons have been taking aim at liberal pieties for decades, using comedy to expose the hypocrisies of their characters and audiences alike. We are now trained to watch shows like “South Park” and “Family Guy” with a reflexive awareness of their ironies and to take their jokes as critiques, rather than celebrations, of racism. But “Archer,” along with other recent shows, does this more skillfully than most. The result is a comedy that is both more entertaining to watch and more confounding to our sense of political correctness.

It’s no accident that animation has been at the forefront of identity comedy. As Hugo Dobson has argued with regard to “The Simpsons,” animated shows participate in the “carnivalesque,” an idea proposed by Mikhail Bakhtin to describe the “grotesque realism” of Francois Rabelais. In the case of “The Simpsons,” Dobson argues, animation allows the show to tackle a wider and more vulgar range of subjects than live action, while providing “an opportunity to ridicule and let off steam against the piety of current political correctness but without going too far.”

Of course, what’s considered “too far” is a matter of opinion and also subject to change. Today we expect comedy to subvert racial stereotypes, but in the past cartoons usually propagated them. Programs from the 1930s and ’40s — a period known as the Golden Age of Animation — took their cues from the vaudeville and minstrel shows before them, and produced titles like “Goldilocks and the Jivin’ Bears” and “Uncle Tom’s Cabana.” A frequent sight gag featured a character getting splashed in the face with tar or ink and appearing, for a moment, like a blackface minstrel-show caricature with bulbous lips and headlamp eyeballs.

Although African Americans were the primary victims of animated racism, other minorities were mocked as well. One black-and-white 1930 cartoon titled “Laundry Blues” showed pigtailed laundry workers speaking Chinese-sounding gibberish and a hook-nosed Jewish customer who comes in to get his beard washed. World War II provided an occasion for anti-Japanese caricatures, such as the infamous Bugs Bunny cartoon “Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips,” in which Bugs does battle with a hapless Japanese soldier on a remote Pacific island, and which puts the recent “Archer” episode in a particularly questionable light. Does Archer worry about being racist because the soldier is Japanese or because he’s inadvertently participating in a tradition of racist animation?

Such examples of overt racism fell out of favor after the war, and in 1968, United Artists, which owned most such cartoons, decided to suppress the most offensive of them. Yet race has continued to be a preoccupation of animated shows, albeit in a more complex way. And the transitional figure, bridging the distance between Golden Age insensitivity and contemporary hypersensitivity, was Ralph Bakshi.

Trained in the Golden Age techniques of the Terrytoons studio, Bakshi began his career in the 1950s as a cel painter on shows like “Deputy Dawg” before going out on his own to create movies like “Fritz the Cat,” “Heavy Traffic” and “Coonskin.” While all three of these films contained over-the-top depictions of blacks, Italians and Jews clashing in the ethnic melting pot of New York, it was “Coonskin“ — an urban retelling of the Uncle Remus tales — that provoked real outrage. At the movie’s premiere at the Museum of Modern Art, Al Sharpton and the Harlem chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality picketed the screening, accusing the movie of perpetuating “racial disrespect” and the black actors who participated in the film of being “traitors to their race.”

These days, black filmmakers have embraced Bakshi’s movies, and few people, if any, still accuse Bakshi of being a racist. But it’s easy to see why viewers were offended. Bakshi was performing a fraught maneuver, presenting traditional racial stereotypes in a nonracist context in order to expose their offense. It didn’t help that Bakshi’s method was particularly blunt. In “Coonskin,” one of his primary targets is a character named Simple Savior, a phony, obese and frequently nude black pastor who tries to milk his flock by inflaming their sense of racial grievance. As author Darius James has written, “Bakshi pukes the iconographic bile of a racist culture back in its stupid, bloated face, wipes his chin and smiles….” Bakshi wasn’t trying to avoid ugliness — he was exploring its depths.

In the end it was the pureness of Bakshi’s motives that made his movies a commentary on racism rather than an example of it. But comedy that relies on motivation is a tricky business. What is legitimate satire, and what is racism masquerading as satire? What is “ironic,” and what is the real thing? As a comedian friend of mine once put it, racial comedy is often only a venue away from a hate crime. In other words, just because you call something comedy doesn’t make it not racist.

Such accusations have dogged Bakshi’s heirs, who have not always been as successful as he was at making meaningful statements rather than just ethnic jokes. Though “The Simpsons” has taken half-hearted stabs at anti-racist pieties, it has also been criticized for stereotyping its nonwhite characters, including the black Dr. Hilberg, Asian Cooki Kwan, Hispanic Bumblebee Man and especially the character of Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, the impossibly hard-working, stingy, superstitious and thickly accented Indian owner of the show’s Kwik-E-Mart.

Other, more provocative shows, like “South Park” and “Family Guy,” have been accused of taking racial comedy too far, and of using the notion of satire as a cover-all defense. Is the depiction of Jews as financial wizards in the 2003 “Family Guy” episode “When You a Wish Upon a Weinstein” a satire of anti-Semitic tropes or an example of them? Is the name “Token” for the token black kid on South Park an incisive commentary on racism or an excuse for it? Sometimes it seems as though self-awareness can become racism’s justification rather than its repudiation.

Fortunately, more recent shows have been increasingly sophisticated, and even sometimes brilliant, when it comes to racial issues. Indeed, the most masterful treatment of identity politics I’ve ever seen comes from “The Life & Times of Tim,” an animated show created by Steve Dildarian that ran on HBO from 2008 to 2012.

At the beginning of the 2010 episode, titled “Jews Love To Laugh,” Tim, a schlemiel-esque assistant at a faceless Manhattan corporation, hears a joke in the office break room: “Three Jews walk into a bar… and buy it!” When he later repeats the joke to his girlfriend’s Jewish colleague (on the assurances of a man named Herschel that the only thing Jews love as much as gold is to laugh at their own foibles), he finds himself ostracized for telling a racist joke. And yet, when the offended party shows up at Tim’s local pub with two friends to prove the joke wrong, they wind up… buying it.

By the end of the episode, after the pub’s Jewish owners have made a colossal wreck of the business by trying to turn it into Manhattan’s only Jewish Irish bar (“that specific niche of really strict rules and very bland foods,” Tim’s friend Stu comments) they decide to sell it back to the original owner at a steep loss, proving, perhaps, that Jews aren’t always so great at business after all. Finally, the bit ends with the now-rich Irish bartender getting drunk and yelling, “Who’s Irish?!”

The episode, which is just over 10 minutes long, is a staggering maze of racial stereotypes and their reversals, wending its way among them until it’s nearly impossible to tell which is which. It comments not only on the shifting valences of racism, but also on the ways that performances of ethnic identity often occur within the context of offense. Is a joke anti-Semitic if a man named Herschel thinks it’s funny? Would a group of Jews have thought to open a bar serving kosher wine and gefilte fish if they hadn’t been spurred on by Tim’s insensitive remarks? The final irony of the episode is that nobody here is really a racist except the original jokester, who’s also the one that gets away with it.

Although “The Life & Times of Tim” was canceled after its third season, other series have taken up the mantle of identity comedy. “Unsupervised,” a show about two 15-year-old best friends that followed “Archer” on FX in 2012, attempted a transparent reversal of racial stereotypes through the character Darius, a middle-class, high-achieving black teenager whose strict parents stand in contrast to the neglectful guardians of the show’s white protagonists. Other programs that have focused more heavily on African-American experience include the “The Boondocks,” about a black family living in a white American suburb, and “Black Dynamite,” a tribute to and parody of Blaxploitation movies, both of which appeared on Adult Swim.

But the longest-lasting and most successful of these shows has been “Archer.” The comedy centers on Sterling Archer, a secret agent and devil-may-care jerk voiced by H. Jon Benjamin. And it’s Archer’s brash personality that seemingly allows the show’s creators to put offensive material in his mouth. As long as you establish that the person spouting offensive views is himself offensive, it becomes okay for him to say such things.

However, a closer examination of “Archer” reveals that the opposite is often true. If the show emerges unscathed from charges of racial or gender stereotyping, it’s not because of a blanket “satire” defense, but because its characters and situations are too original and sophisticated to be mere stereotypes. Moreover, Archer may be an obnoxious womanizer, but he is far from a bigot. (Indeed, the most offensive character on the show is probably Malory Archer, Sterling’s mother and head of the spy agency, who is voiced with intimidating authority by Jessica Walter.) In contrast to the “equal opportunity offender” excuse used by the creators of “South Park,” Archer seems like an equal opportunity appreciator.

This is particularly true when it comes to foreign cultures, which Archer embraces with gusto. When he visits Morocco in the fourth season (“Un Chien Tangerine”), he antagonizes his fellow agent, Lana Kane (Aisha Tyler), by lecturing her on the Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer. The episode also features characters speaking real Moroccan Arabic, a level of detail that rejects a generic, Orientalized “other” in favor of specific representation. Contrast that with the “derka derka” pseudo-Arabic of a movie like “Team America: World Police” (from the creators of “South Park”), which was meant to skewer American ignorance, but didn’t do much to counter it, either.

When it comes to black characters, “Archer” similarly mixes an in-your-face bluntness with more subtle details. The second episode of the latest season sees the return of Conway Stern, a character who first appeared as a “diversity hire” for the spy agency — and whom Malory refers to as a “double whammy” because of his combined black and Jewish identity — before he turned out to be a double agent. More significant is Lana Kane, the show’s main black character and the foil to Archer’s immaturity. Although she superficially conforms to the “angry black woman” stereotype, as a character she has more agency, assertiveness and self-awareness than a simple cutout ever would.

Of course, despite its strengths, it needs to be said that “Archer” — like “The Life & Times of Tim” and most of the other show mentioned in this article — is the creation of white men. And until the creative gates are opened wide to women and people of color, we will no doubt never see the true potential of animated comedy.

But so far, the direction animation has been taking is a good one. It’s long been the case that cartoons aren’t just for kids; the original Golden Age shows were replete with mature themes, as were Bakshi’s movies. But adult content isn’t just about crude language or sexual innuendo. In many cases, animation is at the forefront of the conversations about race, gender and inequality. If anything, these shows help us all speak more plainly.

Ezra Glinter is the deputy arts editor of the Forward. Contact him at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter, @EzraG