How Marlon Brando Became Godfather to the Jews

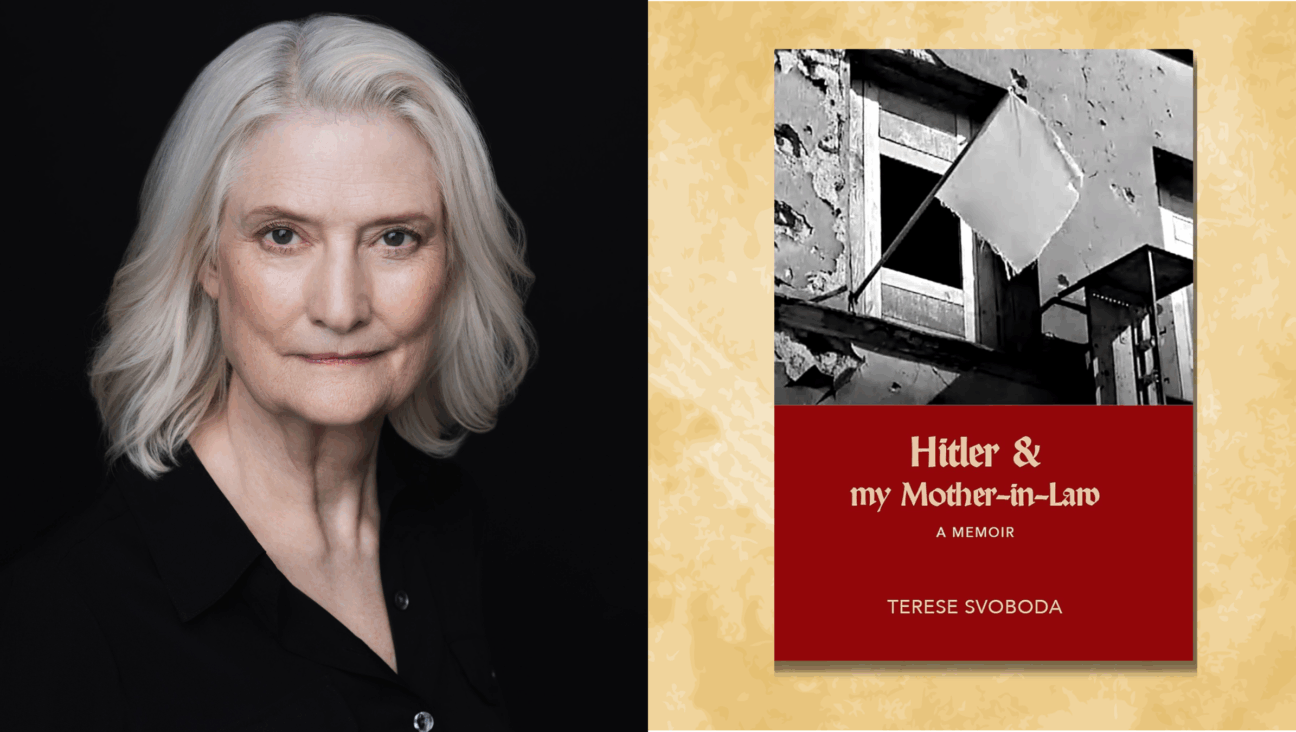

Image by Courtesy of Ellen Adler

Shortly into “Listen to Me Marlon,” a fascinating new documentary about Marlon Brando spoken almost completely in his own voice, comes a startling glimpse of Brando’s life-changing plunge into the Jewish experience of the 20th century.

Drawn largely from diaristic audio tapes he made, combined with a wide range of cinematic imagery, the ruminations start with self-revealing accounts of his first years in Nebraska, growing up with a father who hit him and a mother who drank, and landing in New York in the wartime spring of 1943 “with holes in my socks and holes in my mind.” He confesses, flatly: “I felt dumb.”

He entered The New School for Social Research with its faculty of exiles. “My teachers were all Jewish, because The New School was a clearing house for Jews who came from Hitler,” he says in the voice that inhabited so many outsiders on screen. “But they were respected people, the cream of academia.”

The film moves to other subjects, but that instant embodies Brando’s embrace of Jewish New Yorkers in the depths of World War II, when many Americans had reflexive anti-Jewish views. Otto Friedrich, in “City of Nets,” his book on Hollywood in that era, recalls “how cruel and pervasive anti-Semitism was in the America of the 1940s.” Hotels were closed to Jews, universities imposed quotas, and Ernest Hemingway called a high-ranking Hollywood producer a “heeb” to his face.

Even Tennessee Williams, a fellow Midwesterner with whom Brando’s fate became bound, confided in a letter to his mother in 1940 about Clifford Odets’s sister: “Unfortunately, she’s Jewish.”

Brando — his mother’s family was Christian Scientist, his father’s German forebears were named Brandau — seems to have eschewed even private bias against Jews he met. At The New School, he first studied with Erwin Piscator, an experimental director who’d fled Hitler with his Jewish wife. He switched to Stella Adler, who combined her New York family’s Yiddish theater tradition with new approaches. The Adler family virtually adopted him. He sat at the table in their West 54th Street apartment, picking up Yiddish; reading the Forverts with increasing comprehension; holding it upside down on the subway to study the puzzled reactions of Jews at a time when he was turning the city’s ethnic variety into his college of life.

“Equal to his genius as an actor was his intelligence,” says Ellen Adler, Stella Adler’s 87-year-old daughter, when I visit her in the Greenwich Village apartment where she lives with photos of her and Brando when they were young. She became his girlfriend and stayed his friend until his death in 2004. She says Brando “soaked in the atmosphere” of her bohemian Jewish family, which included Stella Adler’s husband, the important director-critic Harold Clurman. Within Ellen Adler’s reach — near a recent book about Tennessee Williams — lay photos of her grandfather, the regal-looking idol Jacob Adler, and her grandmother, Sara Adler, also a star of the Yiddish theater. Sara Adler also lived in the 54th Street apartment, and she and Brando grew close.

“Marlon fit right in with our Jewish sense of humor,” Ellen Adler tells me. She hands me a photo of Brando in the 1940s, stretching his face at her to look like a Japanese Kabuki actor or gargoyle. “It was jokes, but more than jokes. It was that man walking on Fifth Avenue. It was that woman coming out of the hairdresser. It was the way people talked and what they did. You acted it out. Marlon loved it.”

Godfather and Great Godfather: Brando with Charlie Chaplin. Image by Getty Images

In “Songs My Mother Taught Me” — a memoir Brando wrote with former New York Times reporter Robert Lindsey — he describes his fast-forming warmth for his friends in “a world of Jews,” how they “introduced me to a world of books and ideas that I didn’t know existed. I stayed up all night with them—asking questions, arguing, probing.”

From overseas, news of the Holocaust and Zionist militancy pierced the Adler family consciousness — and his. In 1947, shortly before his explosive fame in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” he played the lead role of David, a young concentration camp survivor in “A Flag Is Born,” a successful theatrical production written by Ben Hecht to raise money to free Palestine from the British and create an Israeli state.

Biographers have gone into Brando’s Jewish involvement before. But, in “Listen To Me Marlon,” for which filmmaker Stevan Riley had the cooperation of the Brando family, we hear his words. His sincerity sounds elemental. The film’s fresh sense of Brando’s self-aware totality has won the film strong reviews; the aspect of Brando’s story that I was interested in exploring was the impact of Jewish culture on his development.

This curiosity led me to Rabbi Marvin Hier, of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, who made a three-hour visit to Brando after he was accused of anti-Semitism during a Larry King interview in 1996. Hier, who says he explores that visit in an almost-finished memoir, didn’t get questioned closely at the time about exactly what Brando said. The rabbi told me that Brando spoke to him, at length, in an elegant Yiddish “like 99% of American Jews could never manage, and with such knowledge of Jewish matters that I could only conclude this man was no anti-Semite.”

He belongs, in fact, to the little-studied history of philo-Semitism. Even in dark times, non-Jews have befriended Jews and been sensitive to Jewish culture. In the 1940s, they included Eleanor Roosevelt and the critic Edmund Wilson, with his passion for Hebrew texts. Brando is certainly the most visible example from popular culture among members of a younger generation who internalized Jewish experience as key to their humanity. The bridges he built to major Jewish theater artists of the 1940s foretold the mutual acceptance underpinning Jewish American identity as it matured after World War II.

“A Flag Is Born,” in which Holocaust nightmare meets Zionist dream, has a vital place in that broader social story, and a direct place in history.

Hecht was a leading screenwriter who co-wrote “The Front Page” and wrote a column in the liberal paper PM. In 1939, he challenged Jewish readers to become more openly Jewish. That drew a response from a man who called himself Peter Bergson, but was actually Hillel Kook, an Irgun leader working undercover in America. He persuaded Hecht to take a key role in winning American support for the Zionist militants. The pair also spread early word of the Holocaust to mostly deaf ears.

In 1947, with displaced Holocaust survivors scattered through Europe, Hecht wrote a story of two older survivors of Nazi brutality who meet a younger one named David, in a European graveyard. After comparing the American revolution and the quest for Zionist independence, the old man expires. David gives way to bitter rage at Jewish destruction, then idealism for a future Israel. “A Flag Is Born,” which Brando joined on a national tour, met its goals of raising money to buy a boat to help refugees get to Palestine and guns for the Irgun.

Luther Adler, Stella’s brother, was chosen to direct it. At his sister’s urging, he chose the gorgeous but awkward 23-year-old from Omaha, Nebraska to play David.

“He was unforgettable,” Ellen Adler recalls of Brando’s intensity. “At one point, he challenged the (mostly Jewish) audiences for their complacency: ‘Where were you, Jews?’ Where were you when six million Jews were being burned to death in the ovens of Auschwitz?’ And a woman got so upset she stood up in the aisle and asked: ‘And where were you?’”

“Everyone in ‘A Flag Is Born’ was Jewish except me,” Brando wrote years later of the cast headed by Hollywood star Paul Muni. And there the pre-stardom Brando stands, in a photograph Adler hands me of him, front and center among about 10 other Jewish actors and activists with the Bergson-Hecht group. “That’s Bergson,” she says, pointing to a man with a mustache. “Look at his shoes,” she laughs, pointing to her old boyfriend, who wears a tie and jacket with what look like sneakers, projecting a dishevelment biographers have described as typical of him at the time.

Brando’s intimacy with Jewish struggle became part of a universal view he expressed of human rights in the 1960s and beyond. In 1963, he joined the March on Washington, where Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. At a televised forum just after the march, sitting with his old friend James Baldwin and other luminaries, he spoke like an eloquent progressive rabbi. He hoped, he said, that the march would benefit “all the minorities,” including “Jews, Filipinos, Chinese, Negros.”

“The problem seems to me to do with hatred,” he told viewers, in a precise tone. “We are all human beings filled with anguish, hatred and fear, and I think that is what we are addressing here today.”

Brando isn’t known to have attended Jewish services, though I found a fun account online of him going to a Seder at a Hollywood synagogue with Bob Dylan in 1975. But he was devoted to Nate ‘n Al, a deli in Beverly Hills, where the private Brando got mostly take-out. “He loved bagels and lox, but didn’t eat much pastrami,” says Avra Douglas, who started with him in 1990 as a young personal assistant and now serves as one of three executors of Brando’s estate. The other two are the producer Mike Medavoy and Brando’s former business manager Larry Dressler. “All three of us are Jewish,” Douglas notes.

“Probably the first thing that comes to my mind when I think of him was his incredible sense of humor, which I would say had a Jewish sensibility,” she adds. “He knew all of the jokes from the old Jewish comics.” Religiously, it seems, the man who played Vito Corleone would get to his TV for the Hollywood Yiddishkeit of the annual Chabad Telethon in L.A., enjoying the music and the jokes: “I think the culture was comforting to him,” Douglas says.

I tell her that watching the YouTube images of Brando with civil rights leaders after the March on Washington and hearing how his passion for Jews extended to his collective sense of all minorities had made a strong impression on me.

“He was a humanitarian,” Douglas responds. “I think that’s a very Jewish thing to be.”

Allan M. Jalon is the winner of two 2015 Simon Rockower Awards for his Forward feature stories, “My Opa’s Story of World War One’s Other Fight” and “A New Jersey Tale of Two Alfred Doblins.”