Jewish? No, We’re Subbotniks. Welcome to Our Synagogue.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Slipping and skating on the icy street, Larisa Semyonova approached an austere gray-brick building and then stopped to greet it as if it were an old friend.

“This was our prayer house — our synagogue,” she said. But now, her modest wooden house farther down Nairyan Street is sufficient for that purpose.

Four pensioners awaited us there, swathed in scarves against the frost. Sixty-one-year-old Svetlana Utkina handed me a tattered siddur, or prayer book. “Compiled by Eliezer Aaronovich Semyonov, published 1907,” its title read. In its 500 pages, I found not a single Hebrew letter; all prayers were in pre-revolutionary Russian. Utkina shrugged: “And why should there be Hebrew? I’m not Jewish, I’m a Subbotnitsa.”

The prayers we read are uncannily familiar, but they may not be heard here for much longer. These five women from the lakeside town of Sevan, Armenia, are among the country’s last Subbotniks.

The Russian language maintains the useful distinction between Evrei, ethnic Jews, and Judei, followers of Judaism, simplifying the complex identity of this religious community. Described as a “Judaizing Sect,” the Subbotniks (“Saturday people” in Russian) were Christian Russian peasants who dissented from Russian Orthodoxy and began to recognize Mosaic Law late in the 18th century, observing the Sabbath, keeping kosher and practicing circumcision.

The Subbotniks’ rejection of Russian Orthodoxy led the czar to banish them from Central Russia permanently, exiling them to Siberia, Southern Russia and distant, newly acquired territories in the Caucasus and Central Asia, in a drive to isolate them from Russian Orthodox peasant communities receptive to their message.

They were joined there by two dissenting Christian groups with earlier origins — the Doukhobors and the Molokans. These spirit warriors and milk drinkers, as their names translate respectively, were spiritualist Christian groups whose pacifism and rejection of hierarchical Russian Orthodoxy did not endear them to the Czarist authorities.

A few thousand Molokans live in tight-knit agricultural communities in Armenia to this day, sharing their story of exile with the Subbotniks.

“On the Sabbath, our day of rest, the Molokans would bring us fresh milk,” one Subbotnik recalled. “On Sunday we returned the favor.”

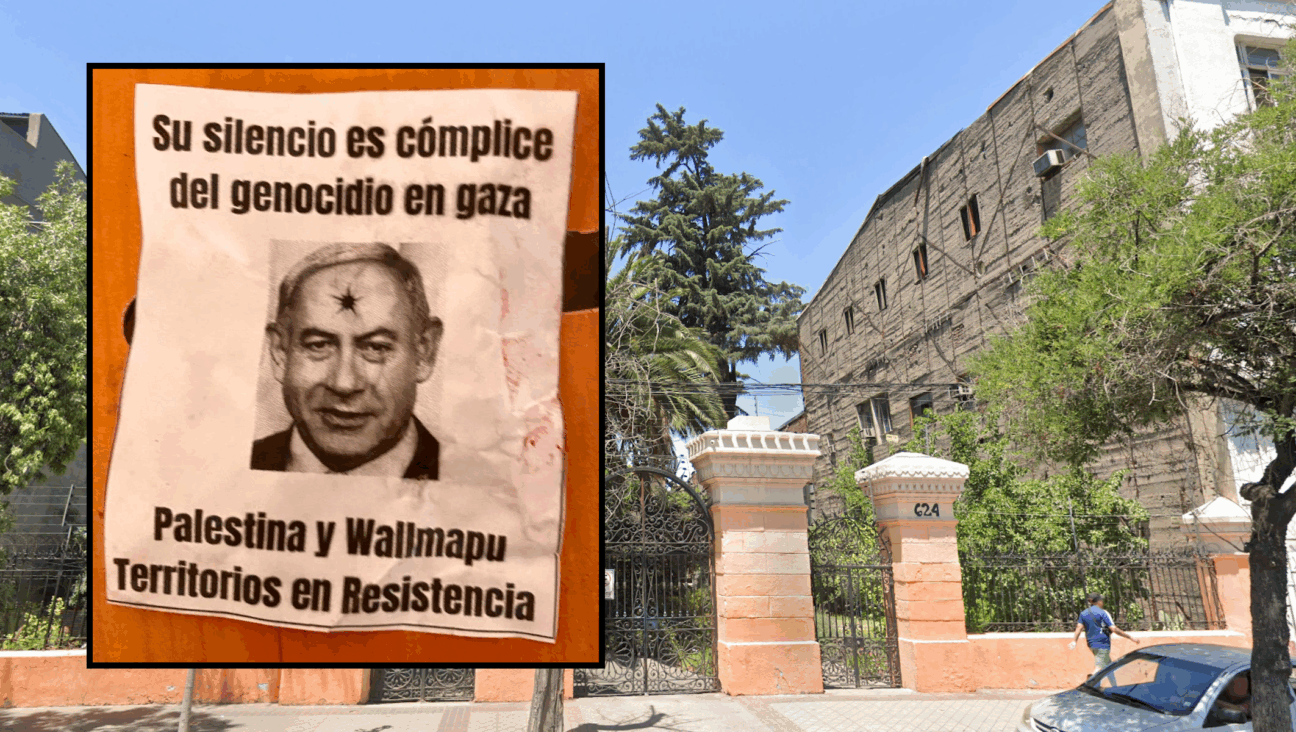

“The Russian Cemetery” where many Subbotniks are buried

“The Subbotnik experience,” Vartan Akhchyan wrote upon interviewing the community for his 2002 documentary on Jewish life in Armenia, “lacks not Judaism but the cultural experience of Jewishness.” Scholar Nicholas Breyfogle noted the unusual situation whereby Jews, as members of a recognized — albeit repressed — religious minority, were allowed to maintain places of worship. But the Subbotniks, regarded as a heretical sect, saw their worship houses closed down regularly under czarist law forbidding the activities of such groups.

The scattered remnants of Subbotnik communities differed in their observance of Jewish custom. But in the late 19th century, several Subbotniks began to contact Ashkenazi Jewish communities and adopt many of their practices. Nevertheless, Sevan’s Subbotniks never sought to convert and are not accepted as Jewish according to Halacha.

Today, this hinders the desire that many have to find a new life in Israel, where they might leave behind the economic uncertainty of post-Soviet states such as Armenia. But they express no regrets about not converting.

“My ancestors did not accept Judaism because they were Evrei,” Semyonova noted. “They did so because it was the purest path to God.”

The Subbotnik community of Sevan is little known to many in Armenia’s minuscule Jewish population in the capital of Yerevan, let alone to local Armenians. In 2006, Subbotnik community leader Mikhail Zharkov estimated that only 13 of Sevan’s 30,000 residents were Subbotniks. Today, Semyonova supposes, there may be fewer than 10.

The descendants of peasants from the Russian provinces of Voronezh and Tambov just east of Ukraine, Sevan’s Subbotniks arrived in 1842 on the shores of the great alpine lake that abuts this town, founding the small village of Yelenovka, named in honor of the daughter of Czar Paul I. It has been known as Sevan since 1935.

The settlers lived short and devout lives, practicing their faith in secret after Soviet rule came to Armenia in 1920. An elder known as the Hakham led prayers and functioned as both the local mohel and the shochet, or kosher slaughterer. The community paid local Armenians to assist them on the Sabbath. It is a time that 86-year old Maria Solovyova remembered well, when some 2,000 Subbotniks lived in Sevan.

“Nothing could break our spirit,” she reminisced over dinner in her small Yerevan apartment. “In those days, we prayed by the hundreds. On one occasion, my father invited Armenian guests to lunch, and they bought sliced sausage with them. When my mother saw it on the table, she swept it up in a napkin and threw it onto the street.” Her father was embarrassed, her mother resolute.

Sevan Subbotniks 1920s-1930s

Solovyova recognizes only Russian names for Jewish festivals: Purim is termed the Festival of Mordechai; Yom Kippur the Day of Forgiveness. Passover for Subbotniks was doubly significant — a communal reminiscence of their ancestors’ arduous journey to Armenia from Central Russia, as well as the Jews’ departure from Egypt. Hanukkah, however, is irrelevant. “We never celebrated it,” Solovyova said. “The story of Hanukkah concerns ethnic Jews — and we are Russians. We are Subbotniki.”

In the Soviet era, Subbotniks, as native Russian speakers, were often employed in clerical jobs in Sevan’s local administration. Their children also received Russian-language education. To this day, many are not fully proficient in Armenian. The closure of their Russian-language school and economic hardship in the early 1990s as Armenia descended into war with neighboring Azerbaijan prompted many to return to Russia. It was part of a broader depopulation of Armenian villages that continues to this day.

With clarity and melancholy, Solovyova recalled the first emigrations of young Subbotniks from Sevan. “We wept as they left,” she said. “We wanted them to come back, they wanted to come back, but there was nothing for them to come back to but our lake and our mountains”

Yet in Southern Russia, many face anti-Semitism and, Semyonova adds, derision for their Armenian-accented Russian.

The Ark of Yerevan’s Mordechai Navi Synagogue holds the community’s one remaining Sefer Torah, donated to the Jewish community for safekeeping. Solovyova remembers that despite their lack of knowledge of Hebrew, Subbotnik elders would always ensure that their scroll was present on Saturday mornings in Sevan, as prayers were read in Russian.

Armenia’s chief — and only — rabbi, Gershon Burshtein of Chabad Lubavitch, noted that Sevan’s Subbotniki originally owned three more Torah scrolls, which he believes they acquired from Ashkenazi communities in Ukraine. One is in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, another has disappeared without a trace and the third was given to a self-declared researcher in the 1980s who vanished after assuring the community that he would return the scroll after submitting it to study and much-needed repair.

Burshtein has a particular interest in the history of the community. Its elders once joined him for prayers, though he could not count them as members of the minyan of 10 men required for public prayer under Orthodox law. When the Jewish community in Yerevan received matzo for Passover, he found that the Subbotniki needed none, having baked their own in Sevan for years. Subbotnik identity, he concludes, is a unique synthesis.

One example of a Jewish-Subbotnik marriage in Armenia is the Sheinin family; a Jewish father and a Subbotnik mother, now living in Israel. That Sevan’s Subbotniki recognize patrilineal rather than matrilineal descent —unlike the more traditional Jewish view — further complicates issues of identity and religious status.

I recall the Subbotnik aversion to celebrating Hanukkah, to which Burshtein added another example. “On Purim, being Jewish, Subbotnik men drank,” he related. “Being Russian, they drank a lot. Accordingly, some of them referred to Purim not as the Festival of Mordechai, but of mordoboi, Russian for a scuffle.”

Svetlana Utkina

The fathers and grandfathers of today’s Subbotniks lie in a section of Sevan’s local cemetery whose gates and gravestones bear crude Stars of David. Abrams, Davids and Eliezers with Russian surnames are buried there, with some gravestones dating back to the early 19th century. A handful of them are dated in the Jewish calendar, though there is no trace of Hebrew.

The snow reached up to my thighs, and, struggling my way across the cemetery, I noticed that Semyonova stood motionless and quietly began to cry. Somebody had stolen the aluminium fence around her parents’ graves — an act not of anti-Semitism, but of the desperation of rural poverty. Local Armenians know this simply as “the Russian Cemetery,” leading on one occasion to a Russian tourist who died by this lake being buried here, beneath a Russian Orthodox cross.

“In another 10, perhaps 15 years” I was told after prayers, “none of us will be left in Sevan. A cemetery and a spirit will remain.”

As Anna Zheltukhina, a woman in her mid-80s, wrote her name and mine on a Subbotnik prayer book and presented the book to me, I was touched and troubled at the thought of such a rare parting gift. Was there nobody else, perhaps one of her grandchildren, who would have more use for it?

“Nonsense,” she replied with a sigh as I set out into the cold. “There’s no such thing as a young Subbotnik.”

Contact Maxim Edwards at [email protected]