Rabbi Hailu Moshe Paris, Revered Leader of America’s Black Jews, Dies at 81

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

On Sunday night, Rabbi Hailu Moshe Paris, who had been at Manhattan’s Beth Israel Medical Center for three weeks, was blinking and smiling at the small group of Jews gathered around his bed. He could not speak, he wore an oxygen mask and was attached to an IV, but he nodded slightly as the group sang hymns and prayed.

Rabbi Baruch Yehuda, one of dozens who called Paris their mentor, held the rabbi’s hand. “It’s me, Baruch, the candy thief,” he said. It was a long-running joke between the two. Despite his diabetes, Paris had always had a sweet tooth, and years ago Yehuda had caught the older man as he was about to unwrap a candy bar. They had ribbed each other about this ever since. This time, to the room’s surprise, Paris opened his eyes, grinned, and let out a rolling laugh.

“He was like the patriarchs whose senses never dimmed, even at the end of their lives, like Moses, like Abraham,” said Rabbi Sholomo ben Levy, who also stood vigil that night. “Rabbi Paris recognized everyone in the room.”

“He had a great sense of humor till the end,” Yehuda added. “He was loved. And I loved him.”

Paris, a revered elder of New York’s black Jewish community, known also as the Black Hebrew Israelites, passed away hours later, on Monday morning.

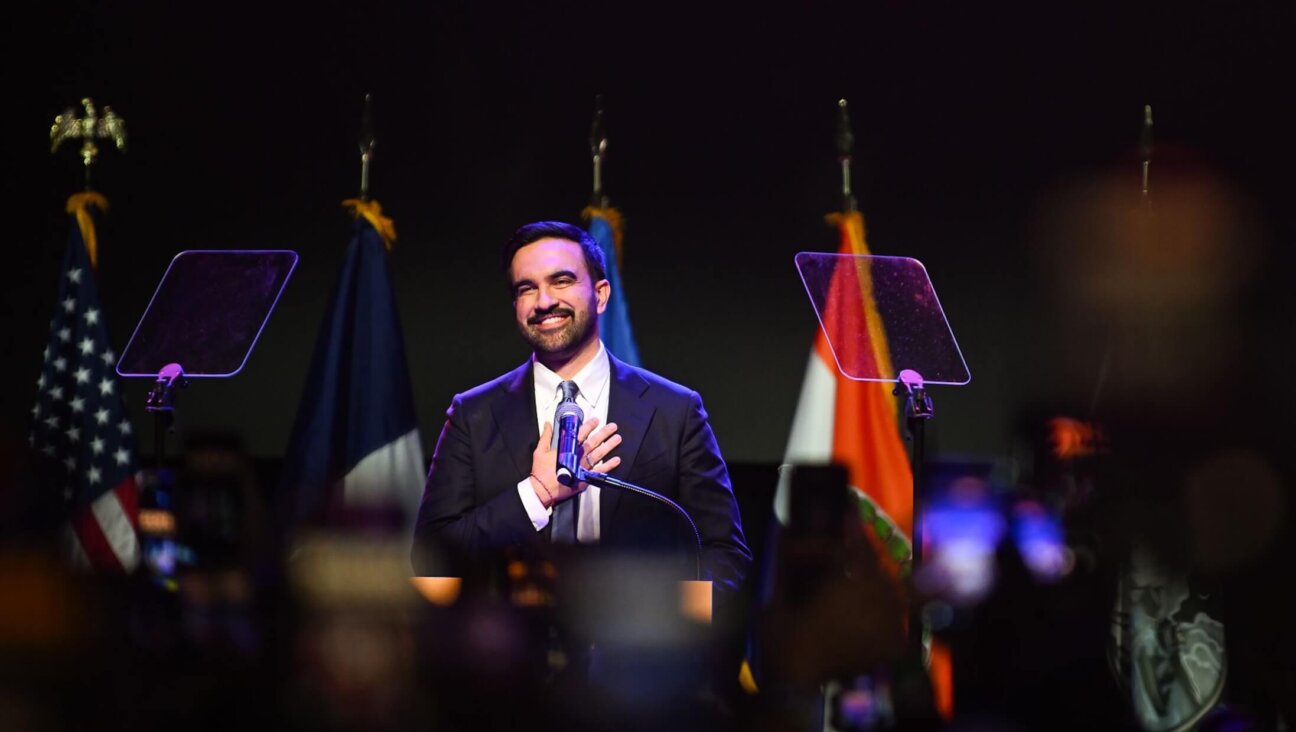

Three days later, it was standing room only at Manhattan’s Plaza Jewish Community Chapel on the Upper West Side as 100 admirers gathered to bid him goodbye.

The venue, a non-profit funerary owned and operated communally by New York’s mainstream Jewish community, seemed fitting. For decades Paris served as a bridge between that normative Jewish world and the oftentimes self-contained black Jewish community of which he was a pillar.

Elder rabbis of Paris’s community, dressed in all white, sat across from of the casket. Rabbi Capers Funnye of Chicago retold some of the dramatic early chapters of the late rabbi’s life that made him such a unique figure.

“We have lost our Moses,” Funnye said. “Stolen out of Ethiopia in the middle of Nazism and fascism, wrapped in a blanket and brought to our shores.”

“I’m here because he was kind to me,” the Jamaica-born philosopher Lewis Gordon said. “He looked me in the eye and knew who I was. The ethical form of God is kindness. He understood that.”

The late rabbi was rolled out in a simple wooden casket adorned with a Star of David and lifted by six members of the community into the back of a hearse.

Born in Ethiopia in 1933, Paris was adopted by followers of the Barbadian rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford, one of Harlem’s turn-of-the-century black Israelite leaders. Raised in New York, Paris grew up to become a revered elder of the Commandment Keepers community, as the group is also known, and a vocal advocate for African Jewry. His story spans continents and centuries, and illustrates the wide spectrum and racial diversity of Judaism.

“Rabbi Paris was a bridge,” said ben Levy, president of the Israelite Rabbinical Academy, where Paris served as rosh yeshiva, and leader of Beth Elohim Hebrew Congregation. “He bridged the African-American community and Ethiopian community and African-American Jewry and European Jewry.”

In 1930, Ford, one of the early black Jewish leaders from New York and a close associate of the black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, led a small group of followers to Ethiopia where he hoped to form a colony that would be a home for black American Jews. It was a migration in line with Garvey’s own partly Zionist-inspired call for American blacks to return to their ancestral African home. While there, Ford connected with the Beta Israel, Ethiopia’s indigenous, centuries-old Jewish community. But in 1935, Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia cut the colonization effort short.

Fleeing the violence, one member of the community, Eudora Paris, set off on a return ship to America. With her she carried a Torah and an adopted Ethiopian two-year-old named Hailu.

According to the story as it has been passed down in the community, their ship was stopped in transit by the Nazis, who were searching for Jews. They looked at Eudora and her child, but because of the color of their skin, the Nazis never suspected they were Jewish. It was the one time racial prejudice about what a “real Jew” looked like worked in their favor, ben Levy joked.

The young Hailu grew up attending the historic Commandment Keepers temple in Harlem, led then by Rabbi Wentworth A. Matthew. Matthew was building on the work of Ford and other Israelite teachers, both peers and mentors, who taught a history which at that time was radical: the descendants of the biblical Israelites had spread across the continent of Africa, he preached, and black Americans, though severed from this history because of the transatlantic slave trade, could return to the Jewish faith.

The message of these rabbis was controversial at the time. But in 1977, the state of Israel recognized the Beta Israel community of Ethiopia as Jewish. More recent cultural and genetic studies suggest that the Lemba of South Africa and the Igbo of Nigeria may also have Jewish roots.

In his twenties, Paris attended Yeshiva University in New York, earning a degree in Hebrew literature and a masters in education. Following this, he taught Talmudic courses at the Israelite Rabbinical Academy in Queens and was an assistant and later head rabbi at the black temple of Mt. Horeb in the Bronx. More recently he served as rabbi emeritus at Beth Shalom, another black congregation in Brooklyn.

The late Rabbi Hailu Moshe Paris, left, with Hebrew Israelite congregants during a Torah service. Image by Chester Higgins

The Ethiopian-born rabbi never married or had children, but mentored many young black Jews. In interviews with community members, he was universally described as a humble, generous holy man, a modern-day tzadik.

Alongside his central role in the black Jewish world, Paris also made crucial connections to mainstream Jewry, as a founder and board member of Hatzaad Harishon, a pluralistic Jewish organization formed to foster interaction between black and white Jewish communities in 1964.

“He was part of the important work Hatzaad Harishon accomplished in redefining who counts as Jewish,” scholar Janice W. Fernheimer wrote in an email. Fernheimer, author of Stepping Into Zion: Hatzaad Harishon, Black Jews, and the Remaking of Jewish Identity, said, “Their lasting impact can be seen in the move toward greater inclusion and diversity we see in contemporary Jewish organizations such as Kulanu, Be’chol Lashon, the Jewish Multiracial Network and others.”

The identity of Paris’s birth parents remains unclear. The academic Tudor Parfitt writes that Paris never self-identified as a Beta Israel; James E. Landing, another scholar, suggested that Paris was born to Christian Copts. Within the Commandment Keepers community, Paris has historically been referred to as a member of Beta Israel.

Whoever his parents were, Paris spent decades campaigning on behalf of Ethiopian Jews. In addition to travelling to Israel on a scholarship from Yeshiva University, Paris made trips to Ethiopia, where he worked with the Beta Israel and the Falash Mura, a related group of Ethiopians with Jewish family connections.

He served on the board of the American Association of Ethiopian Jews as well as other organizations, and was an early activist on behalf of their immigration to Israel. Ephraim Isaac, an Ethiopian-Yemeni Harvard scholar of Semitic languages, served on the board with Paris and praised the late rabbi’s commitment to Jewry worldwide. “There is no question about his legacy,” Isaac said. “He made the Jewish world aware of black Jews, Ethiopian Jews, African Jews.”

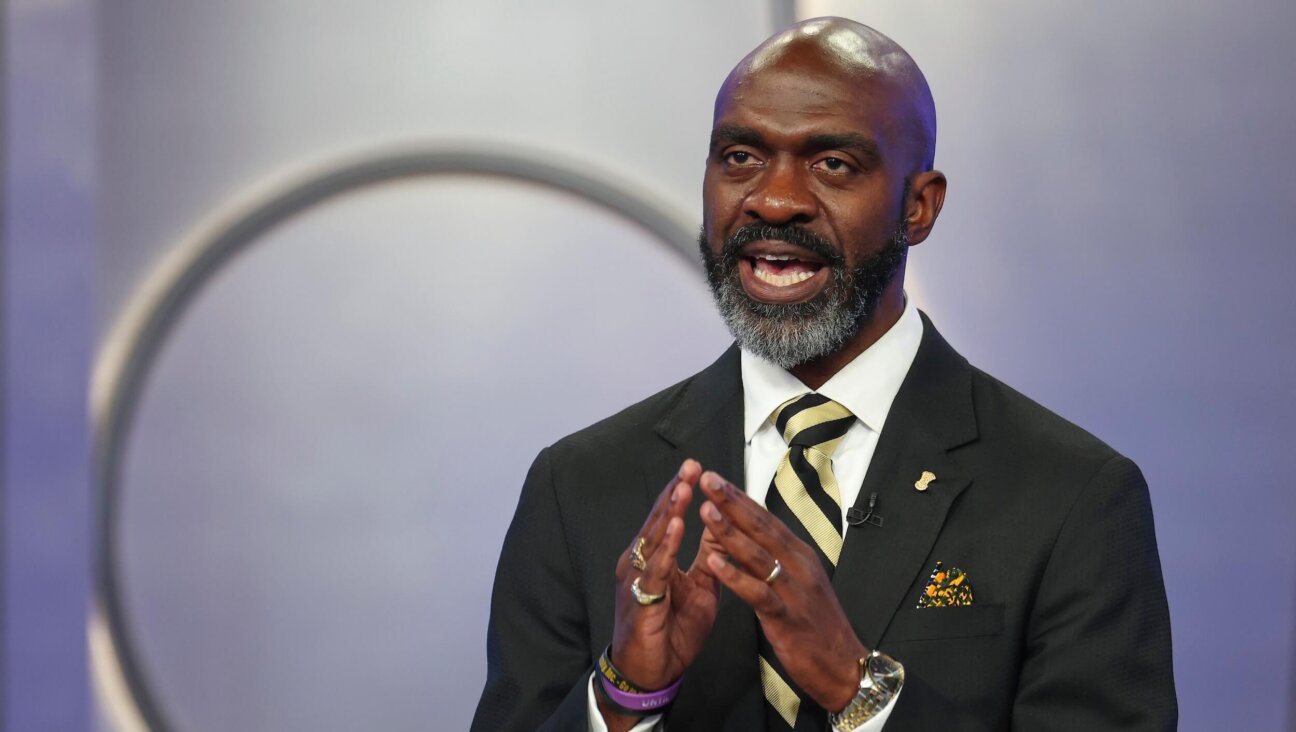

Mourners gather at Rabbi Hailu Moshe Paris’ funeral. Image by Shulamit Seidler-Feller

While Ethiopian Jewry is largely accepted in Israel, the Jewishness of black Americans, specifically the movements which grew out of the work of early rabbis like Ford and Matthew, is still often called into question. A point of contention is the fact that some black Jews, who may also call themselves Hebrews or Israelites, do not formally convert.

Though acknowledging Paris as a community leader, the New York Board of Rabbis does not recognize the Israelite Rabbinical Academy nor any congregations led by its graduates. While this and other perceived slights have led members of the black American Jewish community to isolate themselves, Paris never lost hope.

“Rabbi Paris was always reaching out, despite all of the rejection and questions and doubts,” his friend ben Levy said.

It wasn’t necessarily that Paris thought black Jews needed validation, students and friends recalled. Rather, he believed that if the story of African and black American Judaism was told, the Jewish world would be better for it.

“He was so elated when I told him I had joined the Chicago Board of Rabbis,” recalled Funnye, who leads Chicago’s Beth Shalom B’nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation. “‘Well that’s progress,’ he said. He had an unwavering faith that we would really stop being measured by the pigmentation but rather by our dedication to Torah, by our dedication to the Jewish people.”

Paris’ efforts were also recognized in part in 2010, when the Brooklyn Jewish Heritage Committee presented him with their Kiruv Award.

It was New York City that Paris called home, and in which he lived his entire life. “He knew every street. He knew all the Jewish bookstores and good kosher restaurants,” said Funnye. “He was the best guide to this city.” Paris never owned a car, but had an encyclopedic knowledge of the city’s transit system. “He loved a good deli and taught me to be a connoisseur of matzoh ball soup,” said Funnye.

When the elderly rabbi fell ill a few weeks ago, the news spread quickly in a flurry of messages. “Please offer up healing prayers on his behalf,” one close friend wrote in group email.

Yehuda regularly visited his bedside. “I prayed with him and encouraged him, get out of this thing.” But Paris’ condition worsened. “Death comes after life,” said Yehuda. “You know it’s going to come. None of us are without it.”

The list of academics who relied on Paris for access to New York’s black Jewish community is long; he assisted in almost every study. “And what did they give him in return?” Yehuda wondered. But Paris never questioned the importance of sharing history.

“We daven, we do the Sh’ma Yisrael, we observe just as much Torah as other communities, and in some instances even more, yet there’s still this ambivalence,” Funnye said. “No one is bothering to look at our kavanah [intentions], our ru’ach [spirit], our intellect, at our dedication to Torah and to the Jewish people. All they see is the color. But Paris was the eternal optimist.”

“He just felt our history had to be told,” Yehuda said on the day of Paris’s passing. “If we continue, they’ll get it, they’ll get it.”