Welcome to Queens College, Where Jews and Muslims Dialogue

Image by YouTube

On a recent afternoon in Queens, Secretary of State John Kerry sat with Israeli and Palestinian representatives, chatting amiably. “It’s great to see you two side by side,” Kerry said to the delegates. “Now, have we agreed about these land swaps?”

The Israeli and Palestinian smiled and nodded — a historic agreement had been reached; it seemed there might be an end to the crippling decades long stalemated conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

But then the class period ended.

John Kerry, peeling off a nametag, introduced herself as Rachel Olshin, a Jewish student at Queens College. The Israeli delegate revealed herself as a young Muslim named Amer Ashraf. The Palestinian delegate was a Jew and onetime soldier in the Israeli army, named Jeremy Pitts. The three students were participating in a semester-long simulated peace process at City University of New York’s Queens College, one of a number of measures taken on that campus to ease religious and political tensions.

It is a scene that is markedly different from what has been taking place at four of CUNY’s other senior colleges in recent months. Student interactions on the Middle East have transformed several CUNY campuses into battlegrounds for pro-Palestinian and Zionist groups — sparking a heated debate about both free speech and the boundaries between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism.

The activist group Students for Justice in Palestine, a registered student organization, stands accused of anti-Semitism by the Zionist Organization of America. Right-wing politicians like State Assemblyman Dov Hikind are demanding that CUNY shut down the group, while free-speech advocates and SJP’s defenders worry that SJP is simply being silenced for speaking out against Israel. Amid this, the New York Senate at one point even threatened CUNY with massive defunding for, in its view, failing to respond adequately to alleged incidents of anti-Semitism.

In this politicized debate, one major CUNY school, possibly the city’s most diverse, has been left out of the heated discussions — Queens College.

Here, students do not get into shouting matches or picket on the campus green. The Muslim Students Association partners with Hillel. There are few reports of anti-Semitism or Islamophobia: Jewish students wear Israel Defense Forces shirts and yarmulkes; Muslim women don hijabs and niqabs. There have been issues and hurdles. But, at least recently, no blowups.

“I don’t think anyone has a secret formula for this,” said Félix Rodríguez, president of Queens College. “We all hope that our campus will not be the site of any incident or a series of incidents. What I can say is that I am fortunate to have come to a place that has put thought into preparing the ground for these things.”

Sophia McGee, the Queens College professor who leads students through the simulation, described some of that preparation: “We’re trying to teach empathy here. There are many different narratives in the Middle East, all deeply felt.”

Students study maps in a 2013 Queens College course about the Middle East. Image by YouTube

In 2001, history teacher Mark Rosenblum stood on the steps of the Queens College library, students at his side, and watched the twin towers in Manhattan burn in the distance. Plumes of thick smoke rose above the city. Transportation shut down. Some students camped out in the auditorium. As details emerged, the campus was buzzing and uneasy.

Terrorism, that strange foreign thing, had come to New York.

Rosenblum, an American Jew who had already been involved for years in the Israeli peace movement, decided he had to do something on campus. He saw Islamophobia rear its head just hours after the September 11th attacks. “Alarm bells were going off in my head,” Rosenblum said.

He wanted to move the next generation of students toward nonviolent conflict resolution, somehow untangling the various and competing grievances at play in the Middle East.

Queens College, located in the most ethnically diverse urban area in the world, seemed like the perfect place to do this work. More than half of Queens College’s students are born overseas. They come from some 150 countries and speak 90 languages. Rosenblum calls Queens College “a laboratory for diversity.”

Around 2005, Rosenblum developed a curriculum and course called “America and Middle East: Clash of Civilizations or Meeting of the Minds.” The next years saw slightly different iterations, culminating in the conflict-resolution simulations.

And in 2007, Rosenblum founded Queens College’s Center for Ethnic, Racial & Religious Understanding, which had a similar mandate, but was not only focused on the Middle East.

Since 9-11, history professor Mark Rosenblum has developed several programs that expose Jewish, Arab, Muslim and Christian student to variety of perspectives and first-hand encounters. Image by YouTube

An even more ambitious project came to Queens in 2011: the Ibrahim Project, which—also under Rosenblum’s direction—takes college students on a whirlwind tour of the Middle East: Jordan, Israel, the Israeli occupied West Bank, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

“Students who take these courses, or go on this trip, become the bridge on campus, the shock absorbers,” Rosenblum said.

McGee, who has now taken over Rosenblum’s class, said students are often uncomfortable with the material. And that’s the point. They’re asked to assume characters from “the other side” of where they are coming from.

Students broke up into small groups in different parts of the classroom, peering over maps of the region. Some had difficulty finding Gaza and Tel Aviv on the map. One student struggled to pronounce Bahrain and Kuwait correctly; a young woman in a hijab leaned over to correct her.

A whole range of characters was cast: Amos Yadlin, IDF military attaché to Washington; Salaam Fayyad, former prime minister of the Palestinian Authority; Samantha Powers, United States ambassador to the United Nations, and Turki Al-Faisal, from the Saudi royal family.

“I heard one narrative growing up, not just from my family but from my school and community,” said Olshin, the student who was acting as Kerry. She grew up in a Modern Orthodox community in New Jersey and wore a long black skirt. “There was Israel — the good guys; and then the others — the bad guys,” she said.

For Pitts, the onetime Israeli soldier, it’s even more of a struggle. Pitts spent two and a half years living in Israel, working in Eilat and Tel Aviv, and served in the army, where he manned checkpoints in the West Bank. “It’s hard now to take on the role of a Palestinian,” Pitts said. “I’ve never thought about it from their perspective. There are so many nuances to get a hold of. But it’s eye-opening at the same time.”

Queens College classmates Jeremy Pitts and Amer Ashraf act out Palestinian and Israeli diplomats in a semester-long role playing course. Image by Sam Kestenbaum

Jabeen Cheema, who was born in Pakistan and raised back and forth between her country of birth and the United States, has been involved in Rosenblum’s Center for Ethnic, Racial & Religious Understanding. She never enrolled in the conflict resolution course, but did travel (despite her father’s initial disapproval) on one of the intensive tours of the Middle East.

“Regarding the conflict, I don’t take any side. I’m not pro-Palestine or pro-Israel,” she said, “I’ve learned why Israel is important for Jewish life… but they shouldn’t be transgressing as they make their home.”

If a character is simply beyond the pale for a given student — for example, taking on the role of a Hamas representative, or an Israeli settler — McGee will let that character take a more backseat role. One student confided in a private message to McGee earlier this semester, “It’s really important for me to understand the Palestinians, but I’m terrified.”

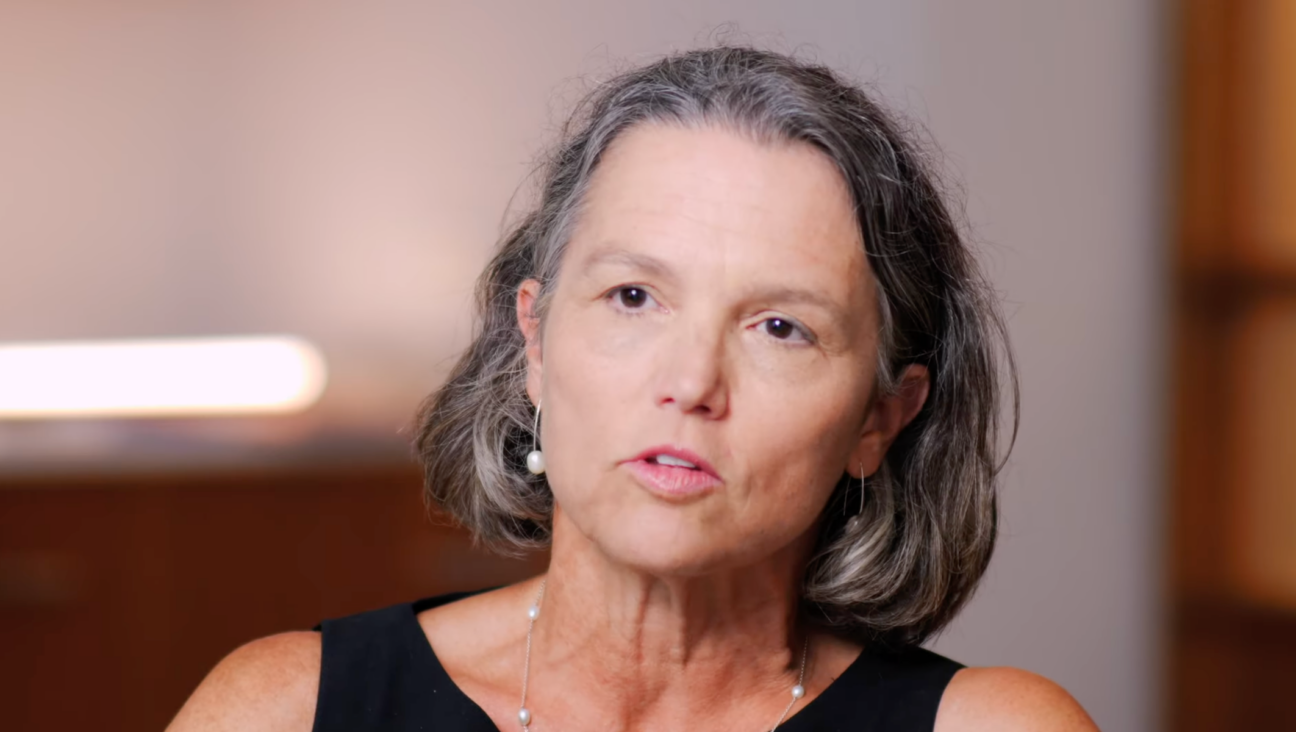

Sophia McGee teaches a class that requires Middle East partisans to argue the other side’s perspective. Image by Sam Kestenbam

The hope is that students who take courses like this will walk away with a “deeper understanding of the other,” McGee said, and spread that sentiment throughout the campus, influencing student leaders, like members of Hillel and MSA.

It seems to be working. But students here are also acutely aware of the political drama unfolding on other CUNY campuses — and in recent weeks they saw some of it finally come to their own school.

Students here have been following the story in real time, starting last November, when ZOA collected testimony from Jewish students at CUNY describing an embattled campus experience. The students spoke of swastikas appearing on desks, chants of “Jews out of CUNY” — and ZOA held the activist group SJP responsible.

SJP advocates for an economic and academic boycott of Israel until it ends its military occupation of Palestinians in the West Bank and an accompanying blockade of the Gaza Strip. It also demands that Palestinians who fled or were forced out of Israel during the first Arab-Israeli War in 1948—and their descendants—be allowed to return to their homes. Israel views this as a de facto demand for the liquidation of Israel as a Jewish state. And some groups, including ZOA, regard SJP’s goals and tactics as anti-Semitic.

SJP firmly denies allegations of anti-Semitism. “We are opposed to the political ideology of Zionism,” said Nerdeen Kiswani, a New York SJP leader.

ZOA pressured CUNY to mount its own investigation into SJP, and the school complied. And New York politicians also threw themselves into the fray — the senate threatening to cut CUNY funding to “send a message” about anti-Semitism, and city council members drafting legislation to monitor racism on campus.

SJP has some supporters at Queens College, but the loosely organized national organization has never gotten off the ground, leaving ZOA little to grab a hold of and object to here.

Batool Chaudhry is vice president of Queens College’s MSA, which partners regularly with the Hillel chapter on campus. Image by Sam Kestenbaum

But in March, the controversy finally came to Queens.

MSA announced that it would be co-sponsoring an event with Hillel about arranged marriages — a topic the group thought pertinent to both Muslim and Jewish students. The group posted a flier for the event on Facebook.

One SJP member from another campus commented, “You’re co-sponsoring with a Zionist organization.” And, as is often the case online, the event exploded — posted and reposted dozens of times, accompanied by incendiary language. “It blew up,” said Batool Chaudhry, MSA’s vice president.

“We canceled the event — for now,” she said, but MSA does not plan on changing its regular meetings with the Jewish group. Muslim students were pressured to distance themselves from Hillel — and Jewish students on campus are also feeling the impact of the wider CUNY controversy, having to sort out for themselves what kind of campus protests are offensive and what kinds are not.

Muslim Student Association advisor Ali Mermer counsels Jews and Christians, too. Image by Sam Kestenbaum

“Not every expression of anti-Zionism is anti-Semitism,” Olshin reflected. Jews should not use the term indiscriminately, she said, nor should its existence be denied. “We may need to draw those lines ourselves,” she explained. “That might be a challenge of our generation.”

Ali Mermer is an imam from Turkey who formally advises MSA but is often seen counseling Jews and Christians, too. Mermer’s office is located next to MSA and across the hall from Hillel. A Quran sits on Mermer’s desk, and he speaks in hushed tones.

Mermer had heard about the protests and counter-protests at other CUNY schools. “College students aren’t always the most patient — for them, they’re right; the other’s always wrong,” Mermer sighed. “Queens College is different. Why? Because we take the precautions.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 2

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 3

Culture How two Jewish names — Kohen and Mira — are dividing red and blue states

- 4

Opinion Mike Huckabee said there’s ‘no such thing as a Palestinian.’ It’s worth thinking about what that means

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Trump’s plan to enlist Elon Musk began at Lubavitcher Rebbe’s grave

-

Film & TV In this Jewish family, everybody needs therapy — especially the therapists themselves

-

Fast Forward Katrina Armstrong steps down as Columbia president after White House pressure over antisemitism

-

Yiddish אַ בליק צוריק אויף די פֿאָרווערטס־רעקלאַמעס פֿאַר פּסח A look back at the Forward ads for Passover products

קאָקאַ־קאָלאַ“, „מאַקסוועל האַוז“ און אַנדערע גרויסע פֿירמעס האָבן דעמאָלט רעקלאַמירט אינעם פֿאָרווערטס

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.