Holocaust Museum Crowdsources the Hardest Question: What Did Americans Know — and When?

Image by U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

How did Americans react to the November Pogroms? What were their thoughts on the annexation of Austria? How much did they know about Auschwitz?

These are just some of the questions that History Unfolded, a crowdsourcing project by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, seeks to answer.

In the past, historians have done extensive research on how major newspapers like the New York Times covered Nazi persecution and the plight of the Jews in Europe.

But no one has looked, until now, at the Bangor Daily News, the Youngstown Ohio Vindicator or the Santa Cruz Sentinel.

The museum is asking the public to comb through libraries to find local newspaper articles and letters to the editors. All the articles are uploaded to a growing online database.

“This is a really unique opportunity for teachers, students, and history buffs to participate in a learning project, where they really are contributing to something important,” David Klevan, an education outreach specialist at the Holocaust Museum, told the Forward.

“This is research that hasn’t been done before.”

Image by U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

In 2018, the Holocaust Museum is set to open an exhibit on the American response to the Holocaust – from the Nazi party’s rise in the 1930s through the Holocaust and World War II.

History Unfolded is part of this larger initiative. Articles discovered by citizen journalists may even appear in the exhibit.

So far, 2,700 people signed up to participate in the project that will run through at least the spring of 2018. They have submitted about 4,000 articles from all 50 states.

Image by Chicago Daily Tribune

History Unfolded “allows access to a lot of newspapers in obscure places that are hard to find,” explained Aleisa Fishman, a historian working on the project for the museum. “A single researcher couldn’t have access to all that,” she told the Forward.

The crowdsourcing research project is also a great way to get students interested in history.

Over 400 teachers are using the project to teach hands on history. One of them is Jennifer Goss from Staunton, Virginia.

“It gives my students the opportunity to do history, to go to archives,” Goss told the Forward.

“Actually making a worthwhile contribution to a historical institution has impacted them greatly,” she added.

Goss implemented the project into her regular US history class as well as into her 11th and 12th grade elective in Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

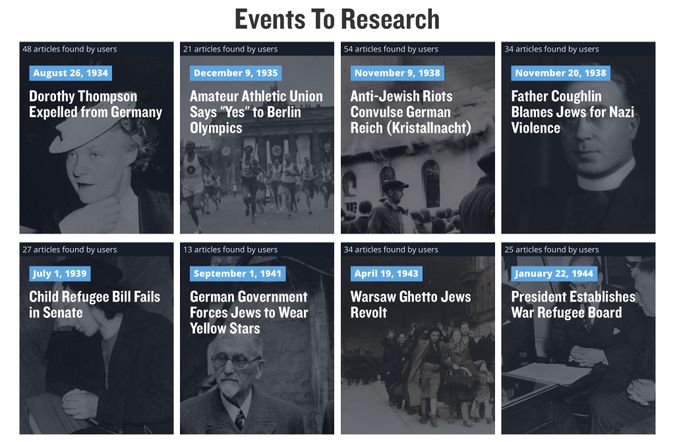

To make it easier for citizen historians, the Holocaust Museum put together a list of specific Holocaust-era events to research: from the opening of the the Dachau concentration camp in Germany on March 22, 1933 to the revolt in the Warsaw Ghetto on April 19, 1943.

Participants look for local news articles, op-eds, letters to the editor and political cartoons and then upload them to the database.

One of the citizen historians who signed up for the program is Bernard Gordon, a retired New Yorker who got the “research bug” in 2015. He analyzed articles in PM, a liberal New York based magazine founded in 1940. Gordon discovered that one of PM’s cartoonists was Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss.

Geisel “was a progressive who used his satirical wit and razor-sharp pen to voice his opposition to anti-democratic forces that came to his attention,” volunteer researcher Gordon wrote in a History Unfolded blog post.

“For example, he criticized Charles Lindbergh in a cartoon within days of Lindbergh’s infamous speech of September 11, 1941. Lindbergh had been generally successful in keeping his antisemitic views to himself until that speech.”

Image by U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

Back in Virginia, Goss and her students were surprised by how many articles they discovered. “Initially, I was skeptical that we would find much of anything,” she said. “Staunton is not very religiously diverse.”

But they found dozens of articles, including eleven focused on the 1933 forcott of Jewish businesses in Germany, an event that might seem small compared to what happened afterwards.

“My students were also surprised that some of the big things that they know about weren’t mentioned” in the local paper, Gross added. “Like Auschwitz.”

Examples like that help illustrate which topics were considered of importance at the time – especially in small town papers.

“It is interesting to see how far the Associated Press wires went,” Fishman, the historian working on History Unfolded said. “Where was it picked up? Is there a local angle? On what page does it appear?”

Asking these questions teaches students what it means to work as a historian and analyze primary source data. In doing that, the participants also learn a lot about their home towns.

When you look for an article about the Holocaust, “you also look at other articles,” Fishman pointed out. “You can see what the community thought to be important and put on page one.”

And then you can ask yourself, what is the relationship between that Holocaust article and what was going on in your community.

Interested teachers or citizen historians can sign up for the project here.

Lilly Maier is a news intern at the Forward. Reach her at [email protected] or on Twitter at @lillymmaier