How College Can Put the Jewish in Children of Intermarriage

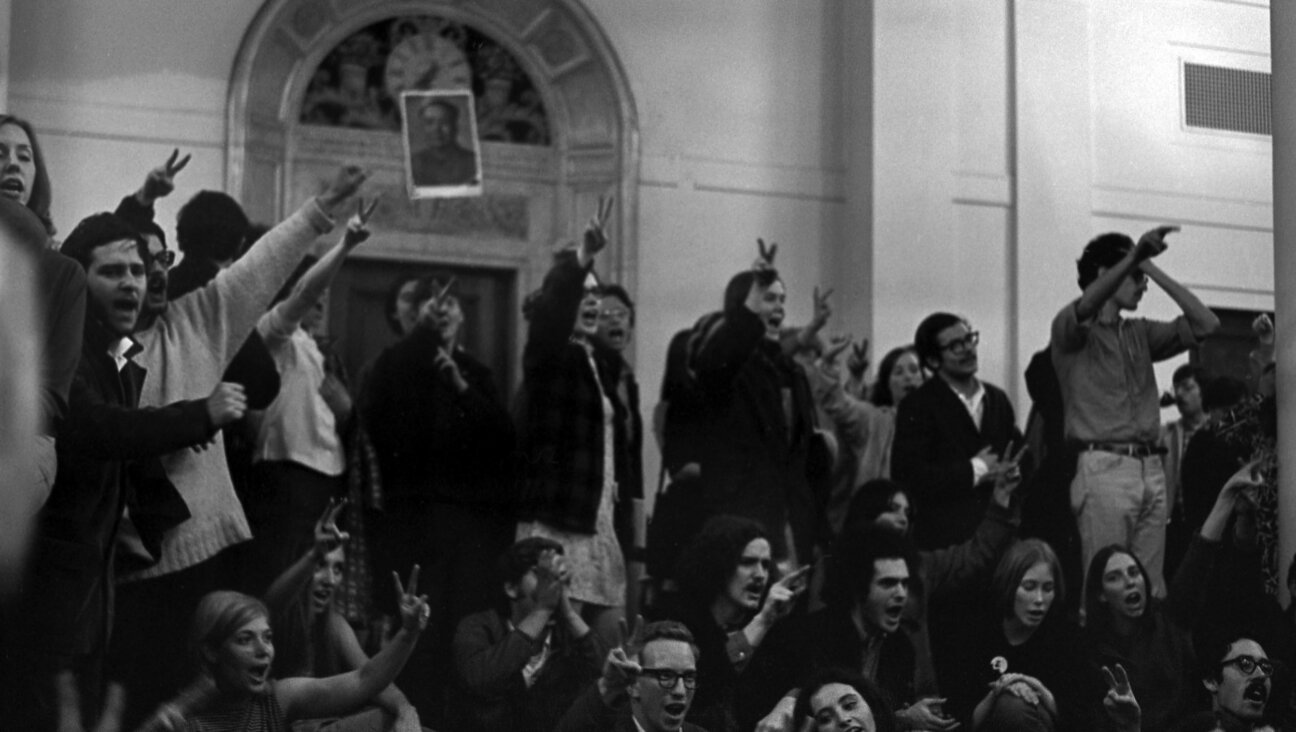

Image by Lior Zaltzman

The late great baseball player and philosopher Yogi Berra once quipped, “It ain’t over till it’s over.” Our new study, “Millennial Children of Intermarriage: Touchpoints and Trajectories of Jewish Engagement,” attests to Berra’s wisdom. Despite decades of worry that American “children of intermarriage” would be lost to the community, a large-scale study of young adult applicants to Birthright Israel found that the story is more complicated, and more hopeful.

Not surprisingly, young adults raised by intermarried parents grow up with a more limited set of Jewish educational and social experiences. However, if these children of intermarriage become involved in Jewish experiences in college — through Birthright Israel, Jewish campus groups or courses — their Jewish identity and later engagement look in many respects very much like that of children of two Jewish parents.

We know from the 2013 Pew Research Center study that 60% of millennials from intermarried families identify as Jewish and that half of all Jewish millennials are children of intermarriage. This prompted us to ask how childhood touchpoints interact with experiences during the college years to shape the Jewish trajectories of millennial children of intermarriage. We interviewed and surveyed nearly 3,000 applicants to Birthright Israel, a sample that resembles our target population of millennials with one or two Jewish parents. Half of our sample was selected from among applicants who were children of inmarriage and half from among children of intermarriage.

We developed statistical portraits of two “typical” millennials: Taylor, a child of intermarried parents, and Jordan, a child of inmarried parents. Taylor grew up with no formal Jewish education or involvement in camping or youth groups, but celebrated Hanukkah and Passover. Taylor also celebrated Christian holidays and occasionally attended Christian religious services. Jordan, as a child, went to Hebrew school, had some informal Jewish education (camps, youth group), celebrated Hanukkah and Passover, and attended Jewish religious services at least monthly. Using these two profiles, we were able to see the effect of various experiences on Jewish behaviors and attitudes.

Some assume that Jewish identity and trajectories of engagement are fixed by the time a young adult leaves home and goes to college. But our findings point to the critical role of college experiences and to the period of development that takes place after age 18. Emerging adulthood is a period of exploration and experimentation and, for millennials, appears to be exceptionally important in shaping their religious and ethnic identities.

If Taylor participates as a college student in Birthright Israel and has some involvement with Jewish groups or courses, profound changes in Jewish attitudes and behaviors become evident. Taylor’s level of engagement in Jewish life looks more like that of Jordan. On some measures, such as participation in Sabbath meals and Jewish holidays, the difference between Taylor and Jordan substantially narrows, but on others, in particular attachment to Israel, the gap is completely closed.

One striking finding relates to Jewish identity. Taylor, without exposure to Birthright and Hillel/Chabad, is more likely to identify nonreligiously. In “Pew Speak, Taylor is more likely to be a “Jew of no religion” than “Jewish by religion.” In contrast, Jordan — even without exposure to college Jewish experiences — identifies as JBR. Taylor, however, is transformed by participation in Jewish life during college and becomes much more likely to identity as JBR.

Skeptics might think that what we have found is simply an artifact of selection bias and that those who choose to participate in college Jewish experiences are more highly motivated. However, although childhood Jewish experiences make it more likely that young adults will participate in Jewish life during college, programs like Birthright Israel attract individuals with a wide range of prior Jewish education. Because our respondents were all applicants to Birthright Israel, and we were able to compare similar individuals who participated and did not participate, we were able to take account of motivation.

Intermarriage has, undoubtedly, changed the contours of the American Jewish community. The Jewish identity of those who are part of intermarried families is less likely to be framed around religious involvement and attachment to Israel. But the key finding of our work is that Jewish identity is malleable for far longer than had been assumed. Meaningful engagement with Jewish life during college, even for those like Taylor, who arrive at college with little prior exposure, can be life-altering.

In 1978, a few years before the first millennials were born, Rabbi Alexander Schindler (then-head of the Reform movement) told his community that intermarriage “does not mean that we should prepare to sit shiva for the American Jewish community. On the contrary, facing and dealing with reality means confronting it, coming to grips with it, determining to reshape it.”

We now have evidence that the Jewish community can, indeed, influence some of the outcomes for children of intermarriage. Engaging the Taylors of the community in meaningful education, whether during childhood or young adulthood, actually makes a difference. Rather than throwing up our hands in exasperation over demographic realities, our findings point to the importance of the community rolling up its sleeves and rededicating efforts to educate and engage all its young adults.

Berra also said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Indeed, predicting the future of American Jewry is difficult, in part because the character of Jewish life is dependent on what we do. Our evidence of the effectiveness of a host of programs that alter the trajectories of Jewish identity and engagement makes clear that the future is in the community’s hands.

The study was carried out with funding from Brandeis University’s Maurice and Marilyn Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies and the Alan B. Slifka Foundation.

Leonard Saxe is a professor of Jewish community research and social policy at Brandeis University and director of the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies and of the Steinhardt Social Research Institute.

Fern Chertok is a research scientist at the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University.

Theodore Sasson is a professor of Jewish studies at Middlebury College and a senior research scientist at the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies .

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30