Kosher Soup Kitchen Struggles With Rising Ranks of Hungry as Passover Nears

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

On a recent chilly afternoon in Queens, two women shivered in a line of about 50 people that trailed out the door of Masbia, a kosher food pantry and soup kitchen.

The first woman, from Manhattan, wore baggy pants. The other, from Queens, was clad in a long, draping skirt.

Their outfits signaled differences in how they interpreted proper Jewish dress for religious women, but both were there for the same reason: They needed kosher groceries, which are more expensive than average, as they try to live on less since food stamp reductions last November.

“When food stamps are cut, it’s hard to buy kosher,” said one of the women, Debbie Greenbaum of Queens.

Masbia, the most robust kosher food pantry and soup kitchen network in New York, is at the forefront of filling hungry bellies — both Jewish and non-Jewish — but not without its own struggles.

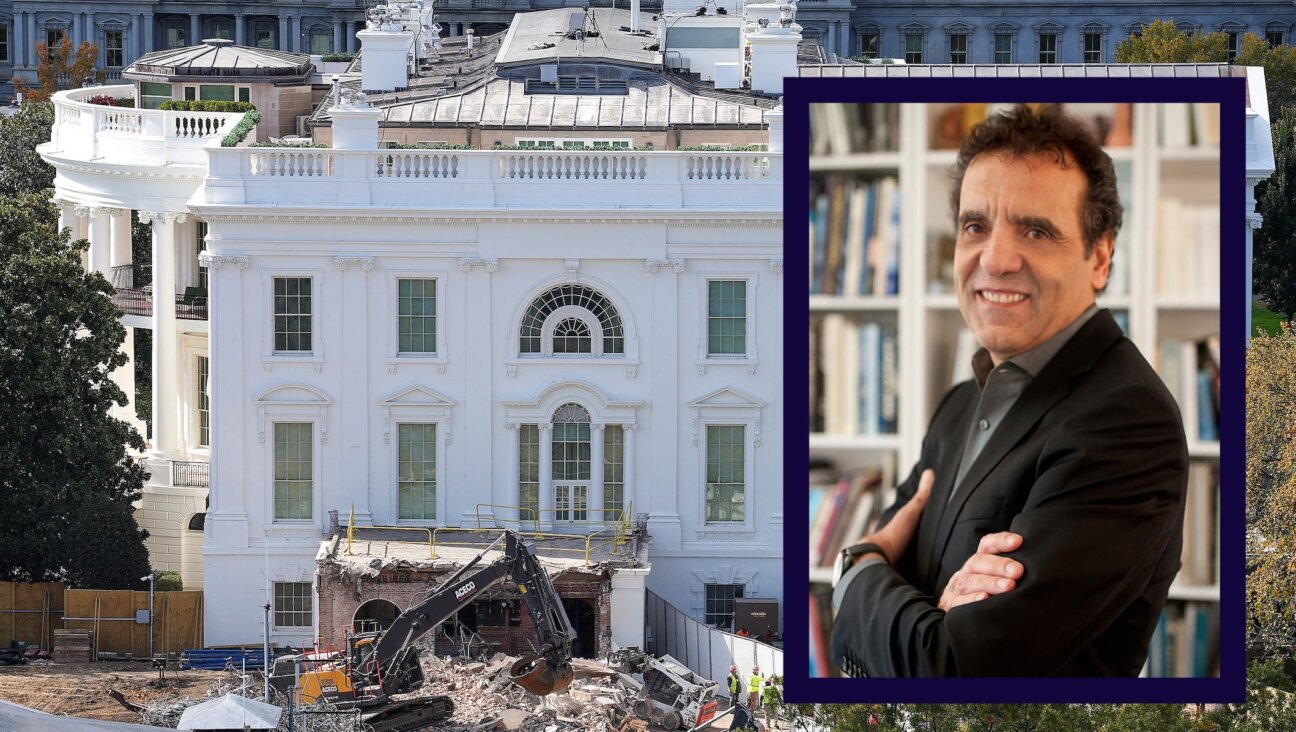

Masbia saw a 200% increase in demand for food in the two months after the food stamp cuts, compared with the same period in 2012–13. The not-for-profit expects to serve up to 1.5 million meals this year — twice the number doled out in 2013. The Queens branch now stays open an extra three hours Thursdays, when food packages are distributed. Alexander Rapaport, Masbia’s executive director, said the organization is operating “hand to mouth.” With Passover coming, he’s racing against the clock to find more funding.

“The most dignified and most efficient way [to stem hunger] is to give people food stamps,” Rapaport said. “We’re not the answer. We’re not the gym — the gym is something that keeps you healthy. We’re the emergency room.” About one in four Jewish families in New York City is poor. About half of those families depend on food stamps, according to Nicole Doniger, chief programming officer of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty.

Overall, one in five people in the city relies on emergency food programs to eat, according to the Food Bank for New York City.

Running a kosher soup kitchen has its own set of challenges. For one, kosher meat is more expensive because it requires additional processing and religious supervision.

Jewish law stipulates a separation of meat and dairy. But to simplify cooking more than 2,500 meals a day, Masbia serves only meat. The organization cannot accept anything containing dairy, and donations from well-meaning people and city organizations are often rejected.

Some foods that are technically kosher are impractical for mass meal production. Take lettuce, which must be washed and checked thoroughly — leaf by leaf — to ensure that all bugs are gone.

While upscale kosher groceries sell pre-checked lettuce, the prices are too high for a budget-conscious charity, which is funded largely on donations from the Jewish community.

Many of the clients, though, are not concerned with whether or not the food is kosher; they’re just hungry.

At Masbia’s Brooklyn locations, in Flatbush and Boro Park, regulars include Latino day laborers. Some are black. In Queens, Chinese and Korean clients line up alongside Bukhari Jews from Central Asia.

Rapaport doesn’t care. What’s important, he says, is filling a need.

He opened Masbia in Boro Park nine years ago, along with his friend Mordechai Mandelbaum, using $100,000 in savings and loans.

Both had seen a need for Masbia in the Hasidic community. And at first, mostly Jews came. Soon non-Jews filed in, too, and Masbia opened in Flatbush and Queens. The changing population presents some cultural challenges.

On a recent visit to the Boro Park Masbia, Rapaport crouched down to pick up a small green pepper from the dining room floor.

“What this proves to me is someone brought food from the outside,” he said, his brow furrowed. “This is kosher, but you never know.”

Before running Masbia became a full-time job, Rapaport, 36, worked as a publicist within the Hasidic community. A jovial, fast-talking man seen only in his uniform of black hat and coat, he promotes Masbia aggressively on Twitter and Facebook.

In Boro Park, near where he grew up and is now raising seven children with his stay-at-home wife, Rapaport shmoozes with kosher grocery store owners and shoppers.

Every conversation is a networking opportunity. Maybe those owners will agree to a good deal on a bulk order of kosher meat. Maybe those shoppers will donate a night of meals to Masbia when their children are married, a tradition in the Hasidic community.

Maybe Masbia will be able to make ends meet.

“If we’re still around, it’s because of tzedakah, because of charity,” Rapaport said. “The awareness is what keeps our doors open and keeps the lights going.”