Third Time’s L’Chaim

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

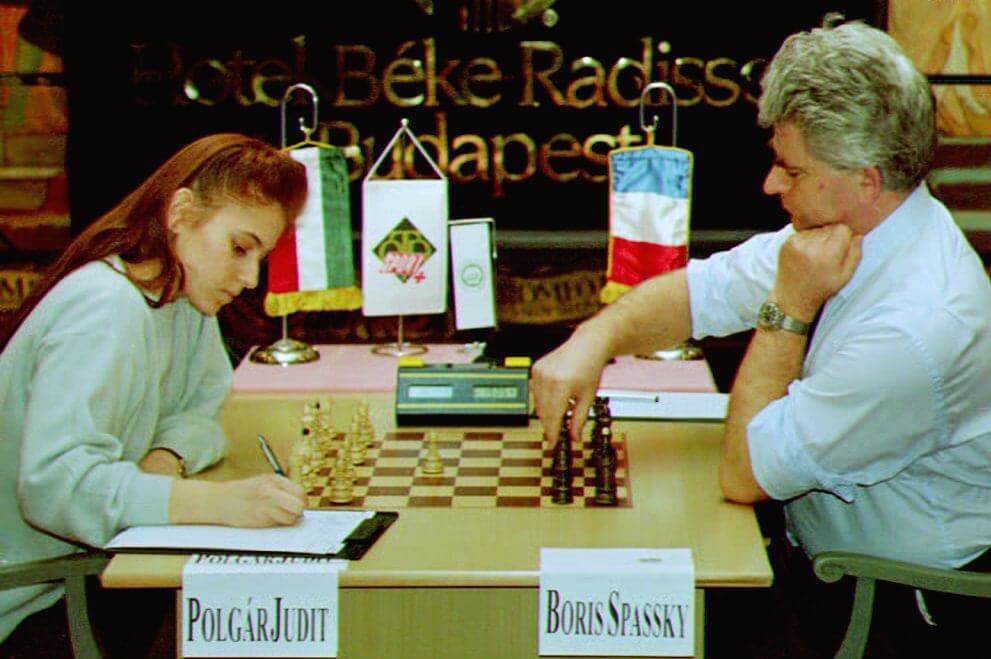

Cheers to You: President Obama and British Prime Minister David Cameron consider their toasting options. Should all of us worry about saying ?l?chaim?? Image by getty images

We can’t seem to get away from l’chaim. At least it’s a happy word.

In two previous columns, as you may remember, I spoke of l’chaim as a Jewish toast deriving from the Kiddush, the blessing said before drinking wine on Sabbath eves and holidays; dismissed several explanations offered by readers as to why Jews in ancient or medieval times might have said to the blessing’s reciter: “[May this wine be] for life,” among them, the fear that the wine could have been poisoned and a custom of giving condemned prisoners wine to drink before their execution; and ended by endorsing the theory, first raised by the 14th-century rabbi David ben Yosef Abudarham, that the original expression was not the Hebrew l’ḥayim, “For life,” but the Aramaic l’ḥayei, “All right,” which was corrupted into l’ḥayim when Aramaic ceased to be spoken by Jews. L’ḥayei would have been said in response to the Kiddush maker’s question of savrei maranan v’rabotai, “What say you, my masters?” when asking permission to begin.

The latest communications about l’chaim come from David Wexler, Zishe Waxman, Gilad Gevaryahu, Michael Halberstam and Rabbi Josh Yuter. Mr. Wexler agrees with Abudarham. So, for slightly different reasons, does Mr. Waxman. Mr. Gevaryahu, who doesn’t, prefers an original meaning of “For life” to “All right” and suggests, based on a passage in the Jerusalem Talmud, that the danger to be warded off was that of wine mixed with unclean or polluted water. (Ancient wine was very strong and generally watered before drinking.) Mr. Halberstam and Rabbi Yuter prefer the “For life” etymology too, but revert to the poisoned wine/executed prisoner hypothesis and offer a seemingly irrefutable argument for it — an explicit passage from the rabbinic compilation of biblical exegeses known as Midrash Tanhuma. Here is the passage, found in the commentary on the Torah reading of Pekudei in the book of Exodus (the bracketed phrases have been added by me, except for the one in italics, which is a variant found in some texts of Tanhuma):

“[After the witnesses in a trial ending with a conviction for a capital crime have been questioned] The Sanhedrin and the people escort them to the city square, and the man condemned to be stoned…. is brought there too, and two or three leading members [of the Sanhedrin] ask the witnesses, Savrei maranan, ‘What say you, our masters?’ And if [they wish the condemned man] to live, they say, l’ḥayim, ‘For life,’ and if [they wish him] to die, l’mita, ‘For death.’ And the man to be stoned is brought good, strong wine and given it to drink, so that he does not suffer…. Similarly, when a prayer leader recites the Kiddush with cup in hand [and fears that poison has been put in his cup], he says savrei maranan, and those present say l’ḥayim, that is, may the cup be for life.”

That settles that, no?

Well, no. Actually, it doesn’t.

There are many rabbinic compilations of midrashim, of which Tanhuma is one of the best known but also one of the murkiest in terms of provenance. Although the first printed text of it dates to 1522, there are earlier handwritten manuscripts; yet these are fragmentary, vary from one another and bear different names. While the consensus among scholars is that a good deal of Tanhuma relies on older sources, numerous attacks made in it on the Karaites, a biblically literalist Jewish sect that originated in the 800s, as well as the medieval quality of its Hebrew, establish that it was almost certainly written no earlier than the 9th century.

The Sanhedrin, to which alone rabbinic law delegated the power to mete out death sentences, ceased to exist with the destruction of the Second Temple in the first century C.E. Furthermore, as I pointed out in my first l’chaim column, even when the Sanhedrin existed, death sentences were extremely uncommon. Nor, in the period between the Temple’s destruction and Tanhuma’s composition — 800 years at least — does any known Jewish text refer to asking the witnesses at a trial whether to carry out or commute the death sentence of a condemned man anaesthetized by wine. What are the chances that the memory of such a rare practice was preserved orally from generation to generation for eight centuries or more until it finally surfaced in written form in Tanhuma? Not very great, in my estimation.

I would say, therefore, that the passage in Tanhuma, far from providing us with a true explanation of the custom of saying l’ḥayim during Kiddush, was itself fishing in the dark with a guess. This would also account for the variant version of “and fears that poison has been put in his cup,” which seems to have been inserted by an editor who put no more credence in the condemned prisoner explanation than I do and was casting about for a different one.

I’ll stick with Abudarham’s explanation of l’ḥayei. It’s simple, it’s plausible and it’s elegant. The Tanhuma asks us to believe more than we reasonably can.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]