How To Confuse a Gentile

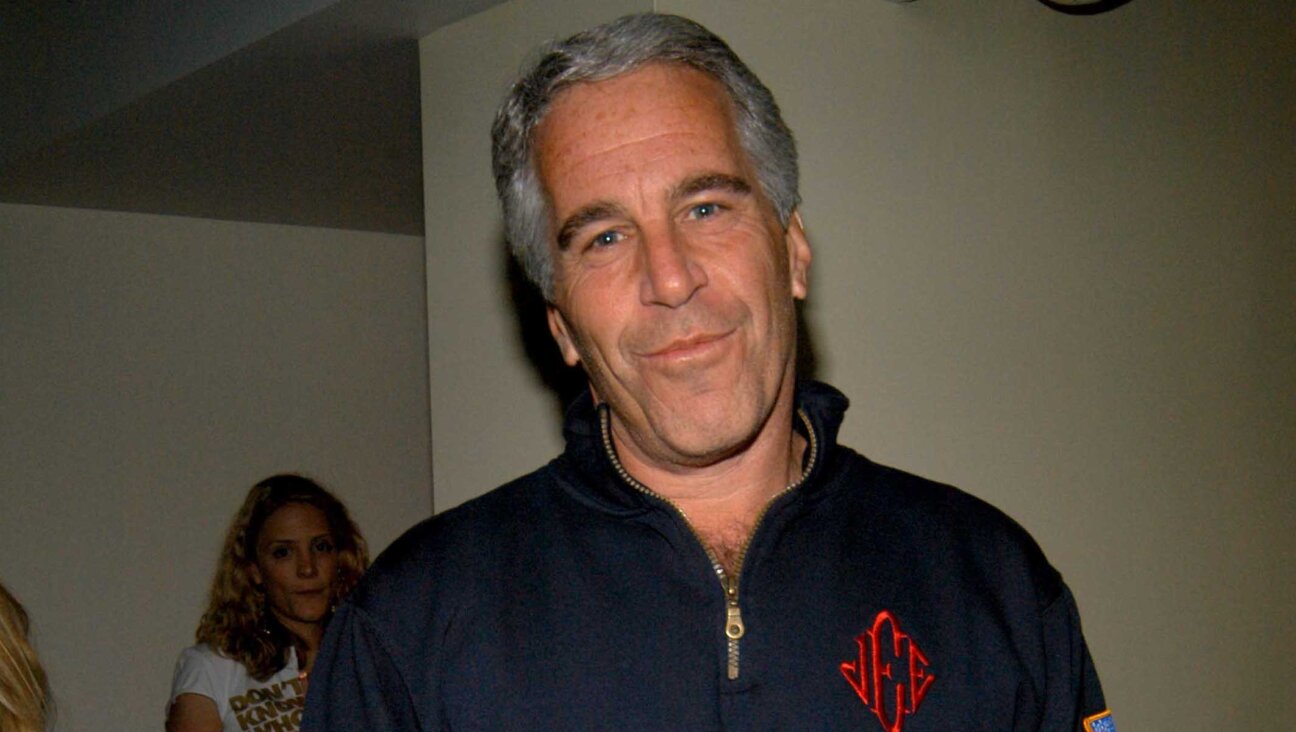

Speak Nisht Evil: Sometimes, our ancestors? language befuddled those who tried to eavesdrop on them. Image by Getty Images

Carol Russak writes from San Francisco:

“My mother, who was from a small town near Chernovitz, used to use the expression daber nisht when she didn’t want to talk about a subject. I know that this means ‘Don’t talk,’ a combination of Hebrew daber and Yiddish nisht. Have you ever come across this expression?”

I have — and it has interesting origins.

The Hebrew-derived dabern, meaning “to talk,” is not a common Yiddish verb. The ordinary Yiddish verb for “to talk” is redn, from German reden, a cognate of our English “to read,” and “Don’t talk” in ordinary Yiddish is red nisht, not daber nisht.

There were circumstances, however, in which Eastern European Jews did not want to use ordinary Yiddish, which was when they were speaking to one another in the presence of Christians by whom they did not wish to be understood. The problem did not arise, of course, with most Christians, because the average Russian, Pole, Ukrainian, Romanian or Lithuanian knew no Yiddish or, at most, only a few words of it. There were more exceptions to this rule, however, than we today might imagine. Before World War I, there were many Eastern European towns and villages in which Yiddish-speaking Jews constituted a majority of the population or close to one, and not a few Christians — neighbors, business connections, customers of Jewish shops or market stalls — had regular contact with Jews. Some of them often learned a considerable amount of Yiddish, and although very few of them were fluent in the language, a fair number could understand at least part of the Yiddish conversations they overheard.

This sometimes presented Jews with a dilemma, especially if they were talking Yiddish to another Jew who, unaware that a Christian in the vicinity understood Yiddish, might blurt out something unfit for Christian ears. What did one do in such a situation? One couldn’t very well say “Red nisht,” because the Christian would understand that, too. The solution was to say “Daber nisht,” using a relatively rare, Hebrew-derived word with which the Christian was far less likely to be familiar.

A good example of this can be found in Sholem Aleichem’s well-known novel “Motl-Peysi the Cantor’s Son.” In one chapter, a Russian policeman stops Motl, a boy of 8 or 9, because of complaints that the Kvas (a Russian soft drink made of fermented barley) that he is selling on the street is watered. The policeman takes a sip of it, spits it out in disgust and asks: “Where did you get this swill from?” Motl truthfully answers that his older brother Elye made it. “Elye who?” the policeman asks, wanting to know Motl and Elye’s family name. Just as Motl is about to answer, one member of the crowd of Jews that has gathered at the scene warns him: “Daber nisht, du narisher yold, af dayn akhi!” That is, “Don’t talk about your brother, you stupid idiot!”

Daber is not the only Hebrew-derived word substituted for a more ordinary Yiddish one in this sentence. Akhi for “brother,” in place of bruder, is another. And the interesting thing about this is that akhi doesn’t even mean “brother” in Hebrew; it means “my brother,” being formed from the Hebrew aḥ, “brother” and the first-person possessive ending “-i.” Moreover, unlike daber, which is a real if not much used Yiddish word, akh in the sense of “brother” does not exist in Yiddish at all. Just what is going on here?

What is going on is comically subtle. The Jew warning Motl doesn’t want to say bruder because he is afraid the policeman will understand that, too, and realize that Motl is being told something about Elye. Yet when he tries to think of a rare synonym for “brother” in Yiddish, he can’t come up with anything. What does he do? He quickly racks his brain for the Hebrew word for “brother” in the one Hebrew text that he has some knowledge of — namely, the Bible; then he remembers the story of the two brothers, Cain and Abel, and recalls Cain’s notoriously memorable answer to God when asked where the murdered Abel is, “Ha-shomer aḥ i anokhi?” “Am I my brother’s keeper?”; and not realizing that aḥ i is an inflected form of aḥ , he inserts it, rather than akh, into his Yiddish warning. Needless to say, Motl, an orphan who has never gone to heder and has no religious education to speak of, has no more idea of what either akh or akhi means than does the Russian policeman, which doesn’t prevent him a moment later from taking to his heels and running away.

To get back to daber nisht, eventually it expanded beyond being used to warn Jews against talking indiscreetly in the presence of non-Jews and became an expression used solely among Jews, with the meaning of “Let’s not talk about it.” This is the sense in which Ms. Russak heard it from her mother, and it was not one limited to the region of Chernovitz.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]: