Judith Malina Joins Jewish Show Business Stars in Next Stage of Life

Good Old Days? Judith Malina still puts on a show, even at 86 and in an assisted living facility for elderly show business types. Image by nate lavey

Anarchist-pacifist Judith Malina, who co-founded the iconic Living Theatre, doesn’t want to be in an assisted living facility at all. Still, she concedes that the picturesque Lillian Booth Actors’ Home, in Englewood, N.J., with its manicured lawns and gardens, is pretty nice. At least she’s among fellow artists.

Operated by The Actors’ Fund, the 111-year-old residence is designed for theater folk — or members of their immediate family — who have worked in front of and behind the footlights and now need assistance with daily living and, in some instances, require nursing home care. At the moment, 124 residents live on the premises, with 82 in the nursing home facility.

The home evokes theater at every turn — from its walls lined with vintage theatrical posters and archival photographs, to its library filled with theater books, to the performers who come in to entertain the residents. Within the past few months these have included K.T. Sullivan, Larry Woodard and cast members of “Mamma Mia!” as well as the cast of “Old Jews Telling Jokes.”

Despite some good times, restrictions abound in institutionalized living. “They don’t let me light my Shabbos candles,” complained Malina, 86. “I’ve told them I’ll just light them for a couple of moments while someone stands in the corner with a fire extinguisher. But they said, ‘No, no, no.’ Instead, they gave me two electrical candles.”

It goes without saying that Malina is not allowed to light up her joints, with which she is keenly identified and hitherto smoked openly. The risk of fire is that much greater because oxygen is pumped into the room — Malina suffers from emphysema.

Sporting black eyeliner and long black hair, the director-actress never anticipated this chapter in her life. Indeed, until February 21 she lived in an apartment on Clinton Street, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, one story above the theater that she and her first husband, Julian Beck, founded in 1946. The building was the last in a series of spaces that housed the theater.

Good Old Days? Judith Malina still puts on a show, even at 86 and in an assisted living facility for elderly show business types. Image by nate lavey

Best known for its communally created productions, awash in anarchistic themes, revolutionary cries and audience participation, the troupe has performed in venues across the globe. But running the place cost $20,000 a month, and despite contributions from Al Pacino and Yoko Ono, and the $800,000 generated from the sale of Beck’s art collection, the theater simply could not make it.

“You cannot cover your expenses with box office,” Malina said. “Every other theater gets some kind of funding, but we didn’t get a nickel from anybody —not the corporations, not the government. They don’t want to fund an anarchist group that wants to abolish money. In the ’60s and ’70s we got funding from the NEA [National Endowment for the Arts], but now they won’t do it; however, we will continue to produce plays in different venues.”

Indeed, the day I visit Malina, she is getting ready to travel into New York City to perform in “Here We Are,” the company’s latest play, which is enjoying an extended run at the Clemente Solo Vélez Cultural and Educational Center, on the Lower East Side.

Malina is now planning to write two new plays, one for the Living Theater and another to be produced at the Lillian Booth. The latter will voice personal advocacy — as opposed to politics — and focus on the indignities of old age and on the lack of respect that many elderly experience despite their enhanced wisdom. “The problem is worse today than it ever was, because prejudices are growing,” she said. “Generally, people are more prejudiced today than they once were.” Malina hopes to stage the work at the home with a cast of residents, or what she only half-kiddingly refers to as “inmates.”

During the interview, she rummages through piles of papers and miscellany to share with me: books about the Living Theatre; old reviews, clips and photos. One picture has special meaning; it features herself, Beck and her second husband, actor Hanon Reznikov, who was also a member of the Living Theatre and was 23 years her junior.

“Hanon said he’d always take care of me,” she said wistfully. To her, his sudden death in 2008 is still shocking. Gazing at the picture, she said, “The three of us worked together and slept together.”

Malina defines herself as a “heretical Jew,” choosing her observances and reshaping others. She fasts on Yom Kippur and eats matzo on Passover, though the theatrical Seders the Living Theatre conducted each year utilized a Haggadah that Malina had revised to reflect a “nonracist, nonsexist” worldview.

Around her neck she sports a peace sign and a ring with the Jewish prayer in Hebrew, “Blessed art Thou, O Lord our God, the Lord is one.”

Lillian Booth’s residents, 35% of whom are Jewish, reflect an array of backgrounds and experiences. Rita Sussman was suffering from asthma and confined to a wheelchair when I visited her (shockingly, she passed away the day after our conversation). She is the mother of pianist Bette Sussman, who performed with Whitney Houston and Bette Midler.

Frail, 97-year-old Jennie Schulman served as a dance critic for half a century, mostly for Back Stage. Harold Cherry, 82, is a veteran regional actor, and the Juilliard-trained Joan Stein, 88, was a member of the chamber ensemble the Walden Trio and an accompanist on NBC’s “Your Show of Shows,” starring Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca.

Indeed, the day I’m at the home, Stein is performing at a memorial for a beloved resident: actress Charlotte Fairchild, who appeared in the original productions of “Mama” and “Damn Yankees.” Audio and video clips are shown, reminiscences offered, and Stein plays, totally from memory, a touching rendition of “Clair de Lune.” It is a stunning performance.

“I try to practice as often as possible,” she said to me following the service. Like most of the others, Stein says she does not look back at her life with a host of what-ifs. She says she would not do anything differently, even if that were possible.

By contrast, Cherry wishes he had had more formal education. Still, he does not disparage his unsteady career as an actor, despite the stream of supplementary jobs he needed throughout his life. After all, he had the opportunity to perform in productions of “King Lear” and “Henry V,” starring, respectively, Morris Carnovsky and Philip Bosco, at the American Shakespeare Festival Theatre, in Stratford, Conn.

To this day, his family is made up of his actor-friends, and they are his most constant visitors. “I never married,” he said. “I liked a lot of girls but didn’t connect with any of them the way I wanted. Without a family, my actor friends became my family.” Raised in an orphanage, he sees a “thread” between his beginnings and his current chapter.

While some of the residents hail from synagogue-going and kosher homes, others do not. Nonetheless, a connection to their Jewish roots is a constant.

Cherry credits the Jewish orphanage he was raised in for his sense of himself as a Jew — culturally, if not religiously — and for introducing him to theater through its annual Hanukkah pageants.

Without being religious, though she grew up in a conservative Jewish home, Schulman says that being Jewish has informed her life and career — not least her boycotting of German dance companies in the years following World War II, though in more recent decades she felt she could no longer hold contemporary Germans responsible for what their parents or grandparents may have done. Looking back, she believes she was ultimately able to review their productions fairly.

Likewise, she approached Israeli dancers with neutrality. Indeed, Schulman says the dancers she observed in Israel were not up to snuff. Asked if she was harsher on them precisely because she was a Jew, Schulman considers the possibility, but is not sure.

Stein suggests that much of her artistry and worldview emerged from her being a Jew. When she was growing up, her synagogue’s cantor said it was important that she know her history. But after Friday night services, “he’d come to the house and sing lieder while my mother played the piano. He called me ‘artiste.’”

Similarly, when she was slated to perform in a secular concert on Rosh Hashanah and worried if she should, an Orthodox woman looked at her and smiled. “She said ‘I think God would be pleased to hear you play.’ I believe when I play the piano, it’s my way of praying,” Stein said.

Stein’s aesthetics and cultural identity are also rooted in internationalism. Her Russian-born father played the baritone horn in the czar’s band in Imperial Russia and had a non-Jewish patron when that was virtually unknown. Still, when the czar’s final edict came down, dictating that all Jewish musicians in the band convert to Christianity or leave, Stein’s father left.

“In the arts, people are international citizens,” Stein said. “Think about Daniel Barenboim, with his youth orchestra of Israelis and Palestinians. They are not in agreement politically, but they are able to get together through their music.”

Stein believes that her Russian, Hungarian and Jewish ancestry all inform her music. But then, so does her life in America in general, and in particular New York City, where most of her music teachers and many of her colleagues were Jews. She also cited the feminist influence of her mother, a professional pianist who made more money than Stein’s father when that arrangement was socially frowned upon.

“I had had a sheltered life in McKeesport, Pa., where I grew up, but I was able to come to New York by myself when I was 17-years-old, thanks to the support of my family, community and culture,” Stein recalled.

Malina also came of age in a cosmopolitan family. Her father was a conservative rabbi for German Jewish congregations in New York, while her mother was an aspiring actress. Accepting the idea that she could not be a rebbetzin and a performer, she — and her husband — encouraged Judith to pursue a career in theater.

Malina sees the Living Theatre’s central vision as Jewish. She pointed to her necklace: “‘The Lord is one.’ It’s the fundamental concept of Judaism, which is the unification of everything and everyone.”

“My pacifism, my politics, my art, are all based on ‘The Lord is one.’ Holiness is our unification, and every play we do is about unification, reaching toward what I call the beautiful anarchist, nonviolent revolution. And for me that means unification.”

Religious services for Jews and Christians are available in the home, though according to all accounts they are “ritual-lite,” often taking place at times that are convenient for the home but not traditional for the holiday. Passover was celebrated in the middle of the afternoon during Passover week, not on the first night of Passover.

Sussman said the home’s Passover service made her nostalgic for the full-fledged Seders she and her husband used to host in their home. The Four Questions made Cherry reminisce about childhood Seders, But personal evolution has occurred, and, perhaps not surprisingly, the final line of the service, “Next Year in Jerusalem,” has a different impact than it once did, at least for some of the residents.

“There’s so much conflict all over the world, and I feel we just need to be more constructive rather than destructive,” Cherry remarked. “That line makes me a little uncomfortable.”

“I don’t get into the political,” Stein said. “I have friends with differing views on this subject, including friends in Israel. The Seder has new meaning for me, mostly because non-Jews are sharing in the experience. And that’s a good thing, because it brings people together.”

Malina also celebrates the home’s inclusive Seder. “I want everyone, but especially the goyim who are present, to be aware that it’s a feast of liberation and redemption from slavery, not in the past but in the future,” she asserted. “When I say ‘we’ are slaves, I mean everyone. When we say, ‘Next year we’ll be in Jerusalem,’ it means we will all be where we want to be. The concept of Zion is not a place in the Middle East, it’s a place of holiness that should be everywhere and could be anywhere, and this is becoming more pressing and more important everyday.”

It’s late afternoon and the sun casts shadows across the floor in the lounge where the memorial had taken place earlier. A few stragglers remain sitting and chatting with plates of fruit on their laps. The mood has lightened. Life goes on.

Perhaps Malina speaks for all the residents when she says, “I’m proud to have survived, but it’s also lonely to have survived.”

Simi Horwitz writes frequently about theater for the Forward.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture Should Diaspora Jews be buried in Israel? A rabbi responds

-

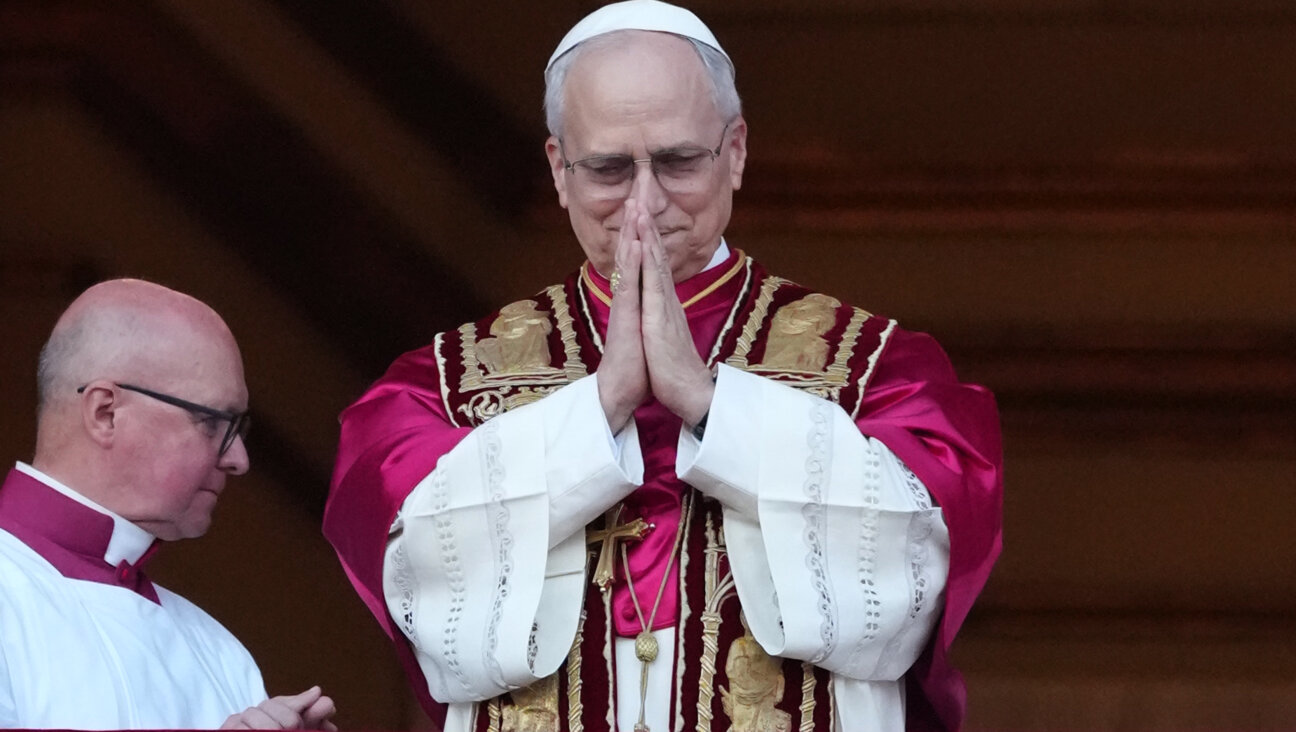

Fast Forward In first Sunday address, Pope Leo XIV calls for ceasefire in Gaza, release of hostages

-

Fast Forward Huckabee denies rift between Netanyahu and Trump as US actions in Middle East appear to leave out Israel

-

Fast Forward Federal security grants to synagogues are resuming after two-month Trump freeze

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.