Honoring Elie Wiesel, They Read ‘Night’ Aloud. Here’s What They Learned.

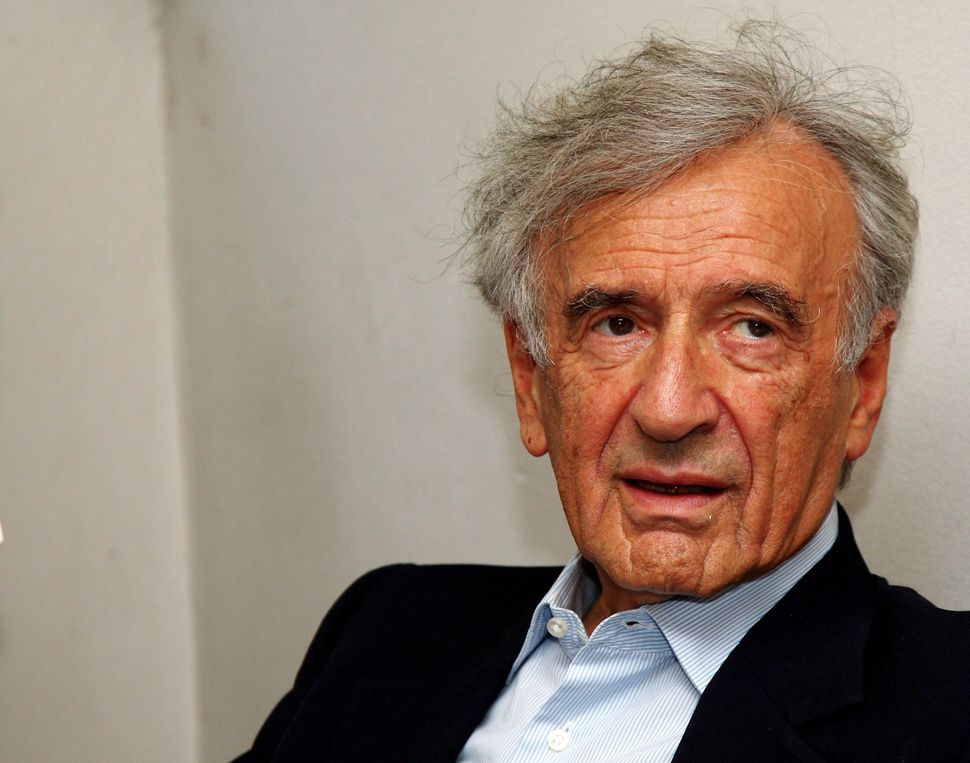

Image by Vittorio Zunino Celotto/Getty Images

“Enter this place, passerby,” Michael Glickman said on January 29, “and meet those who survived the nightmare. Meet them, and learn from them.”

He stood temporarily in near-darkness, on a nearly empty stage. Projected behind him, the face of the late Elie Wiesel, author of those words, loomed in triplicate: Light, shadowed, and almost fully obscured.

Glickman, President and CEO of Manhattan’s Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, was introducing a program at the Museum designed to honor both the memory of Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning champion of Holocaust remembrance who passed away this past July, and International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which had occurred two days prior, on January 27. (The program was co-produced by the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene.) Over the next several hours, a parade of cultural luminaries, politicians, artists, survivors of atrocities across the globe, and more would read the entire text of Wiesel’s “Night” aloud.

Outside the Museum’s walls, in Battery Park, thousands of people stood and shouted in the cold, protesting President Donald Trump’s executive order, issued on Holocaust Remembrance Day, denying entry to the United States for immigrants, refugees and Syrian citizens. The order – since suspended on the order of federal judge James Robart – prohibited access to the country for immigrants and refugees for periods of 90 and 120 days, respectively. For Syrians, it dictated, the gates would be closed indefinitely.

The ban, seen by many as directly targeting Muslims, was stark framing for the reading; “Night,” a seminal book about the horrors of the Holocaust, illustrates the immense human harm incurred by extremes of prejudice. For many readers that illustration felt, given the context of the executive order, especially necessary.

“[Abe Foxman] said Wiesel would have condemned and criticized the refugee ban that had just been announced two days earlier, and I ended up saying the same thing,” said Forward CEO Sam Norich, one of the event’s first readers, after the reading. (Foxman is a member of the Museum’s board of trustees, as well as the director of its center for the study of anti-Semitism.)

Still, said the Forward’s editor-in-chief, Jane Eisner, who had also been one of the readers, “this was not a time for politicking or opinionating.”

“I think that the message was that genocide can happen,” she said. “Wiesel himself, throughout his life, really acknowledged the horror that befell the Jews should awaken us to the horror befalling other people.”

Reading the opening passage of the book, which Wiesel was known to call his “deposition,” rabbi and author Irving “Yitz” Greenberg struck a somber tone. The work, weighty in itself, gained an unexpected immediacy in being spoken aloud, Norich and Eisner agreed.

Glickman said the same. “It was perhaps the most meaningful program I have ever been a part of in my professional life,” he told the Forward, “and I think there was just, there was an air of hope, and there was an air of commitment to cause.”

“Every one of those readers came to that stage prepared to deliver their section in the best possible way. Having all of those very distinct voices made that work all that much more powerful.”

Some of those readers were famous – actresses Tovah Feldshuh and Jessica Hecht, violinist Itzhak Perlman, and choreographer Bill T. Jones, to name a few – but many were, more poignantly, lesser-known, giving voice to the breadth and depth of Wiesel’s impact. Consolee Nishimwe, an author and a survivor of the Rwandan genocide, read; so did Jacqueline Murekatete, the founder of the Genocide Survivors Foundation. James O’Neill, commissioner of the New York Police Department, read; so did Muhammed Drammeh, listed onstage, simply, as a student.

Scattered amongst them were Holocaust survivors, in whose voices Wiesel’s words will always hold particular power – and particular horror.

For one of those survivors, Leah Klapholz, the event marked a turning point in her presentation of her past.

“For 36 years of my life I was a principal of different Jewish schools,” she told the Forward over the phone. “I never, ever, identified myself as a Holocaust survivor to the people that I worked with or the children that I worked with, the parents and their grandparents. That was a very private piece of me.”

“When I accepted this honor I had great trepidation, so I stepped forward there, trying to control my inner emotions,” she said. “I’m constantly at the verge of tears, so you don’t want to be embarrassed, obviously, put up this absolute front.”

Asked if Wiesel’s work had struck her in a new light, read aloud, Klapholz said no.

“I have relived all that many, many times,” she said. “I’m 81 years old now. So I understood that book inside out.”

What moments from the event stayed with her?

Folksbiene Artistic Director Zalman Mlotek reading in Yiddish, for one, she said. “[For] those for whom the Yiddish was their mamaloshen, I could almost feel their response to it.”

The other came at the very end, as Elisha Wiesel, Elie Wiesel’s son, came to the microphone to read his father’s 1986 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech.

“I had never heard that speech before, I never read the speech before, and especially I suppose it resonated so much because of the kind of world we are living in today,” Klapholz said.

Elisha Wiesel shared Klapholz’s perception of that resonance. Speaking to the Forward, he noted the power, for him, of a particular consonance of events on the day of the event: the reading, the protests, and his grandfather’s yahrtzeit.

That power crystallized around protesters he saw on his way to the event.

“It made me feel that my father’s words had translated into action somehow,” he said, “that here while we were reading this book which in so many ways is a call to action – as was his Nobel speech – here were Americans, New Yorkers, wanting to define for themselves this new generation, what our stance should be to people in need of the safety that this country has to offer.”