‘March Madness for Jews’: Why the Sarachek tournament is such a big Orthodox deal

For all the ways the sport unifies the Orthodox world, there is nothing like basketball to draw out its differences.

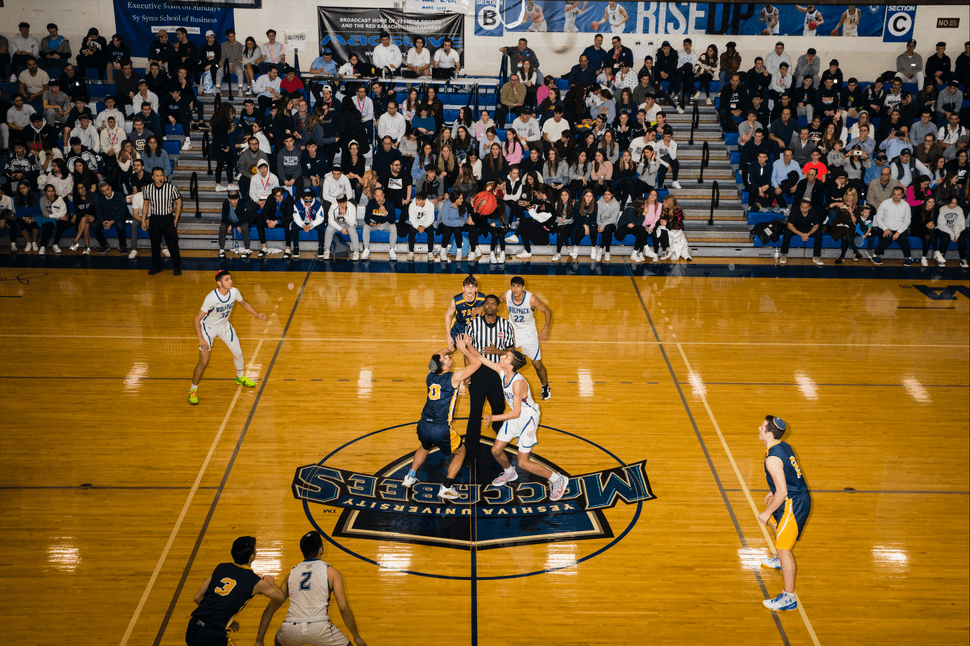

Let the games begin. Photo by Jackson Krule for the Forward

Basketball brought the New Jersey teen to the Yeshiva University gym, but he was neither playing nor watching the game. It was the first day of Sarachek, the annual basketball tournament for Orthodox high schools hosted by YU, and the risers were gradually filling in.

Like hundreds of other students from across the country, Yaakov Gelfond had made the trip to Washington Heights to support his school’s team; Torah Academy of Bergen County (TABC), was playing later that afternoon. In the meantime, and trying to ignore some intense cheerleading led by a rabbi a few rows in front of him, Gelfond was learning Torah.

Mainstream Orthodox Jews in the United States disagree on a lot of things — whether women can teach Talmud, what blessing to make on blueberry pie, the appropriate length for a sermon. But there is nothing that unifies them like basketball. That was true before YU’s team became a national sensation; before high schools started hiring not just one full-time coach, but multiple assistants; before the Jewish jocks got jerseys with their names on the back and school-branded warmup gear, too. But today’s Orthodox high schools don’t just have courts — many of them have million dollar gyms, and the sport has become a pillar of an Orthodox education. Every March it’s on full display at Sarachek.

The tournament is a recruiting tool, a networking event and a reunion all rolled into one, but above all it is a testament to the depth of Orthodoxy’s love affair with basketball. What the 24 teams invited this year lacked in height and athleticism they compensated for not with hustle — though there was certainly plenty of that — but with skill. These were highly trained, fiercely competitive student-athletes whose teams practiced four times a week leading up to the tournament. There’s no hiding it: winning Sarachek is a huge deal.

“It feels like March Madness for Jews,” said Ryan Turell, the graduating YU basketball star and NBA draft prospect, whose loss in the Sarachek finals as a high school senior still stings. “As a high school kid it’s awesome. You’re on top of the world — playing in front of the whole Jewish people.”

As the single-elimination tournament progressed over the next few days — Sarachek runs from Thursday to Monday, breaking for Shabbat — the intensity of the games picks up. The crowds swells until the gym could no longer hold them. The risers sag under their weight.

Gelfond, the TABC student, thinks it’s all a bit much.

“People are so focused on the basketball part,” he said. “The Torah part doesn’t cross their mind.”

A tournament of their own

It originated as a soft sell to prospective YU undergraduates: bring Jewish high schoolers for a basketball tournament so they can see what the country’s flagship modern Orthodox university is all about.

The man who came up with the idea in the late 1970s, former YU coach Johnny Halpert, still comes to Sarachek — his son coaches this year’s top seed, SAR Academy. Halpert admitted that the notion of recruiting high schoolers was just how he got the YU admissions department to pay for rented gym space. The real impetus for the tournament, which is named after Red Sarachek, the legendary YU coach who died in 2005, was simpler. “I thought yeshiva kids should have their own tournament, like the other high schools do,” Halpert, 77, said.

Building parallel to secular society is something like an organizing principle of modern Orthodoxy, whose adherents engage contemporary culture but are limited by tradition from fully assimilating into it. So: kosher Mexican restaurants, schools that teach Mishnah in the morning and A.P. biology in the afternoon, and, of course, a college whose Division III basketball team doesn’t play on Saturdays. These institutions enable Orthodox Jews to enjoy the riches of American pluralism without compromising on identity.

In this sense, basketball may represent a final frontier of acculturation without assimilation: it’s a driver and signifier of coolness in American culture, and broadly speaking, Jewish teams don’t compete at an elite level. To be sure, no one would confuse this tournament for an Adidas basketball camp. But if Sarachek is where the Orthodox world lives out the fantasies of American sports, the participants have left little unrealized. Kids lace up $180 Air Jordans, wear neon compression sleeves on their legs, activate their muscles with Theraguns. They invent elaborate pre-game handshakes and mimic the self-aggrandizing celebrations of NBA stars. Their girlfriends watch from the stands.

The self-seriousness of the tournament — the games are live-streamed in 4K by YU’s peerless broadcasting crew — has helped make wins and losses the stuff of community lore. Aryeh Ivry, one of this year’s standouts, grew up watching Sarachek and wanting to play for Long Island’s DRS Yeshiva High School. He can name past Wildcat stars; having become one, Ivry said, “I’m doing my dream.” When a tournament legend, now a YU student, dropped in to watch his alma mater, kids in the stands whispered his name.

Even at a first round qualifying game at Sarachek, the tournament’s founder, who coached YU for 42 years, can get worked up. Halpert tried not to second-guess his son’s strategy. But in the third quarter he started chastising the SAR players from the risers: “Pass and cut! Don’t hold the ball!” After one bad miss, he buried his head in his hands.

Eventually SAR captured the lead and won comfortably. Afterward, Halpert grinned, a little embarrassed. “What happens is you get caught up in it as you keep watching,” he said.

More than a game

The action is on the court — but also in the crowd.

Abe Behar flew in from Houston with Robert M. Beren Academy — he’s the team’s sixth man. When he wasn’t playing, he was the most colorful person in the stands: blue-tinted ski goggles, black-and-gold Louis Vuitton sweater, and a fro that would make Jimi Hendrix proud. Popping up at every big play, he looked like a diehard fan of every team.

An extrovert who goes to school with only 44 other students at Beren, Behar thrived off the energy at Sarachek. He doesn’t consider himself Orthodox, and he never went to Jewish summer camp. But his connection to the Orthodox community was galvanized through basketball. On the court, he expresses his Jewishness in a way he typically doesn’t in public by wearing a kippah — “especially coming from Texas, wearing a kippah is a huge deal,” he said. And in the risers, he made friends with people from schools he didn’t even know existed before the tournament.

“To see all these Jewish schools from all over the country come to one place, it’s something that you just can’t take for granted,” Behar said. “Like, this is something that you’ll only be able to experience going to this school. That’s it.”

In Sarachek’s male-dominated environment — it’s a boys-only tournament and the gym is on YU’s men’s campus — women make up about a quarter of the crowd. Some of the girls — and plenty of the boys — roll their eyes at the way their schools glorify basketball. But the high school girls who go to Sarachek say they’re having fun, too. They meet other frum girls from around the country — more than one told me she’d met her seminary roommate for the first time — and enjoy an unsupervised senior trip.

Plus, they know the boys — and the sport. One senior girl, Kayla Berkowitz, only needed six words to explain basketball’s supremacy in the Orthodox world: “It’s the most interesting to watch.”

As Behar took in a first round game, a player from Fuchs Mizrachi School, a Cleveland-area yeshiva, picked up a loose ball at halfcourt and raced the other direction. The entire crowd rose as Ephraim Blau — remember that name! — took two dribbles, took off on one foot and dunked the ball with his right hand. The building descended into chaos.

Blau did a raise-the-roof gesture, then blew a kiss to the fans behind his team’s bench. “I told you he could dunk!” Behar exclaimed.

If you build it …

Basketball wasn’t always popular with leaders of the Orthodox world. The European-born rabbis of mid-century America viewed sports as a Hellenistic endeavor that would pull Jews away from the spiritual realm. But their students grew up playing the game, and eventually some of them became rosh yeshivas themselves.

Rabbi Ari Segal, the former head of Shalhevet High School, in Los Angeles, played at Sarachek in the 1990s, and makes an annual pilgrimage to watch the games and catch up with colleagues. Segal showed up to this year’s tournament wearing a half-zip with his name and SHALHEVET BASKETBALL stitched on the chest. (He’s still the school’s chief strategy officer.)

Segal is an admitted basketball fanatic who oversaw construction of Shalhevet’s new building, in which a gym occupies most of the ground floor. But he maintains that the sport is venerated there the same way any other extracurricular is — in that students who are passionate about it are offered every tool to excel.

“There’s real pride in taking something really seriously,” he said. “And the lesson that the kids see is that if you put your mind to something, you can do things you didn’t imagine. I think that’s true not just in basketball. It just happens that basketball has turned into this perfect storm.”

For Shalhevet — from which this writer graduated nearly 15 years ago, before Segal arrived — building a winning basketball program also has been a bid for acceptance by other Orthodox Jews. Hoping to change the narrative around his school, which has historically attracted more liberal families, Segal launched a high school basketball tournament at Shalhevet — like Sarachek, but with fewer schools and with a girls’ bracket.

The core of his tournament is still basketball, Segal said, “but the surrounding piece is, come see that we’re a mainstream, normal school.” It was not unlike YU’s plan: “They’re gonna walk our halls, walk around our building and get a vibe, and you’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, it’s an Orthodox school.’”

The schools have plenty in common, and plenty to make each one distinct. But when the ball goes up, sportsmanship abounds. Photo by Jackson Krule for the Forward

‘Geshmak to be a yid!’

The risers were packed to the ceiling for the semifinal game between SAR and DRS, and the air felt like the space between the crockpot lid and the cholent. Behind each team’s bench were hundreds of rowdy teenagers in their school’s colors.

Simply by virtue of being Orthodox but not Haredi, the schools playing at Sarachek represent a segment of the American Jewish population that amounts to about 3% according to a 2020 Pew Research Center survey. By any standard of comparison, they are incredibly similar to each other in makeup and in practice. And yet for all the ways the game unifies them, there is nothing like basketball to draw out their differences.

SAR and DRS hail from Riverdale and Woodmere, respectively — both New York strongholds of Orthodox life. But at Sarachek they might as well be different religions. Unlike DRS, SAR is coed, with a more progressive religious outlook and a more liberal student population. On one end of the court two or three hundred Christmas-tree-green-clad DRS fans sang Yibaneh HaMikdash — build the third Temple. On the other end, SAR kids howled the super secular “Seven Nation Army” guitar riff. (Later, the DRS faithful started chanting “We keep Shab-bos!” at SAR for about five seconds before an apoplectic DRS rabbi cut them off.)

The SAR basketball team prepares to take the court. Photo by Jackson Krule for the Forward

School spirit connects with sports more than other extracurriculars, but why should anyone care about having attended one Orthodox school over another?

Shalhevet’s Segal said pride in your school contributes to pride in what you’re learning there — that is, Jewish belief and practice — which is mostly the same across these high schools. “You see that you’re part of something bigger when you’re here,” he said. “You’re like, ‘I’m part of this thing, modern Orthodoxy.’” What he’s saying wasn’t so different from what Yaakov Gelfond said: When you’re focused on the basketball part, the Torah part doesn’t cross your mind.

Led by a lefty guard who attacked the paint like a running back, SAR built a double-digit lead in the fourth quarter, putting the Wildcats on the ropes. A DRS basket cut the deficit to nine with five minutes to play and set off their fans, who started chanting their anthem. It’s a song whose last line is about how “delicious” it is to be Jewish.

Someone once came over to me

And asked me what it’s like to be a yid

This is what I told him

This is what I told him

This is what I will tell him

It’s geshmak to be a yid

Geshmak to be a yid!

DRS scored 14 of the next 19 points to steal the game, their fans rushing the floor as the final buzzer sounded. Then the pandemonium subsided, and the teams lined up to shake hands.