99 years ago, she was born on the Lower East Side (and she still remembers everything)

Paula Goldstein recalls living across the street from the Forward Building, FDR, WWII, Kennedy, Khrushchev, 9/11 and a whole lot more

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

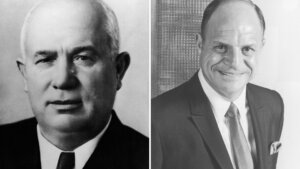

I’m not positive why I asked my Aunt Paula what she thought about Don Rickles and Nikita Khrushchev. I guess because Rickles and Khrushchev looked alike. To backtrack (easy to do when an article is three sentences in), I’d asked my auntie, who just turned 99, permission to publish a story of her (mostly) 20th-century recollections. Everyone who turns 99 should have their recollections published, although don’t ask me to help you with it because I would never get any shopping done.

I had a few notes but no checklist of questions, and yet, Aunt Paula was unfazed by anything I asked, no matter how much of a non sequitur it seemed to be. Paula Goldstein (“Aunt Peshie” in the family) is unfazed by anything, which has a lot to do with why she is 99. This snowbird lives in a condo in Florida but migrates north when the weather warms. After so many Zoom visits, I could actually spend real time with her in her sparkling clean New Jersey apartment she keeps to be close to her daughter. She gave me a seltzer, and I launched in.

Nixon?

“A crook. I never liked him! How could I? He was a Republican!”

JFK?

“A bit of a flirter. We all know he liked women, but I think he couldn’t help the attention. He was so impossibly handsome. Every woman in America was in love with him.”

Don Rickles?

She made a face. “Such an obnoxious man! Maybe some people like that type of humor. I guess I was not one of them. Jack Benny, yes. Fred Allen, good. Those guys were hilarious. George Burns and Gracie Allen were also hilarious. Of course, if you’re talking about all-time comedians, it doesn’t get better than Sid Caesar. Maybe Bill Maher.” (Bill Maher?) As for the famous Oscars slap, she sides with Chris Rock. “That was wrong. How do you defend assault?”

And Khrushchev?

“I have him right here!” she said. She headed to a shelf, grabbed a wooden matryoshka doll with a chubby bald man, and handed him to me. “I visited Russia once, in the 1970s, and I brought back lots of tchotchkes. This is Khrushchev. If you open him, there’s Stalin, and inside Stalin is Lenin.”

I had never held three dictators at once, I said.

Aunt Paula laughed and sat back down.

“Are those New Balance?” I asked, pointing to her sneakers.

“Yes, I wore my Pumas out.” In her new sneaks and her black leggings, she opts for daily walks, which keep her 5’3″ nonagenarian frame fit. (My aunt amends this with, “I was 5’3” – Now, sadly, I am more like 5 foot!”)

It was fun to interview someone who I’ve been close to since I was a child, and I felt honored to learn even more about my aunt. Even if I first approached her in a way that was sometimes irreverent, I think she was gratified to know that her memories were valued. Eventually, we settled on a chronological approach to getting her memories down. We began with her reminiscences of the ten-story Forward Building on East Broadway.

“It was the tallest building in the neighborhood, like the North Star of the Lower East Side. If you got lost, you just looked for the building. When I was a very young girl, my parents’ tenement apartment was 103 Monroe St. When we lived in the back part and then the front, which was a slightly improved living situation, my parents installed a small bathroom right in the living room.”

The Forward Building was also near her schools, PS 2 and PS 177, and Seward Park High School. “Not to mention Hebrew school,” she said.

I was surprised girls were sent to Hebrew school. “Yes, unfortunately, twice a week,” she said. “Of course, the girls in our family were expected to read Hebrew. We came from rabbinical stock, with great yicchus, pedigree. All the women in our family could read Hebrew fluently.” (My great-great-grandfather Chaim Yaakov Shapira was the chief Dayan (chief judge) of Jerusalem. According to elaborate charts, Paula and I are direct descendants of Rashi via two of his daughters – as well as the Maharal of Prague. But pedigree didn’t pay the rent.)

In Jerusalem, my mother said, we were something. But in Manhattan, we were as poor as they came.

“My parents had emigrated to New York, partly for the Abba to escape conscription in the Turkish war, partly because he had become less religious,” Paula said. “My father was part of a long unbroken lineage, and studying to be a rabbi, but he didn’t believe as much as he was supposed to believe, and decided he wanted to be a pharmacist. In Jerusalem, my mother said, we were something. But in Manhattan, we were as poor as they came.”

The Forward, though, was a simple pleasure even immigrants could afford.

“I used to buy the Forverts for my parents because they read that religiously, as it aligned with their socialist politics. They would give me a few pennies, and I would wander down to the candy store on Market Street to get the newspaper and then bring it back. But they didn’t read Der Morgen Zhurnal, another Jewish paper that was too conservative for their taste. The Morgen Freiheit, a communist paper, was also not for them. So they just read their Forverts back to front. They sometimes shared the ‘Bintel Brief’ at dinner for family discussion. On weekends, the newspaper printed special pictures in sepia. We all loved looking at them.

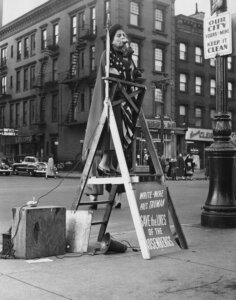

“On Election Day, The Forverts would have a big screen set up on the front of their building. Then, when it got dark, the whole neighborhood would come and look and see the results of the election projected against the building’s wall. But before the results were ready, they had cartoons of Mickey Mouse for the kinder, the children. After the mothers and children went home, the men would wait for the projections.”

Even my aunt marvels at the changes she has lived to see.

“Back in those days, there were no streetlights,” she said. “Just crossing the street was dangerous. There weren’t that many cars on the Lower East Side, but horses and buggies were everywhere. And you had the businesses attached to buggies, like the knife sharpener and the iceman, that kind of thing. Eventually, we got streetlights, which were a major help.”

As immigrants, it was quite an adventure without a car. It was luxurious to sit in the sun, bake a bit, and stroll on the boardwalk.

Paula doesn’t romanticize tenement life too much, nor did my father, who died in 2020 just before his 100th birthday. Still, she holds a special place for Coney Island, reachable from the Lower East Side by subway. “As a family, we traveled there once a year, departing from East Broadway. As immigrants, it was quite an adventure without a car. My mother carried a huge shopping bag full of food and towels. We rode the BMT subway in our bathing suits under our clothes. It was luxurious to sit in the sun, bake a bit, and stroll on the boardwalk. We didn’t have the money for the rides, but that was fine. After returning home, we were exhausted but satisfied.”

Paula smiled broadly, remembering my immigrant grandmother when she came back from the beach. “She always sighed loudly and said ‘home sweet home.’ We were tired, and even a tenement bed was enough.”

There were charity escapes too. Over 600 impoverished children from the Lower East Side and other immigrant neighborhoods could attend summer camp in Mountainville, New York, in the Catskills of Orange County. Camp Felicia was run by the Ethical Culture Society for the very young. Camp Madison was run by the Lower East Side’s Madison House Settlement up in Tomkins Corners, New York, for older kids who outgrew Camp Felicia. Paula has many fond memories of these trips to the Catskills.

One of my aunt’s earliest memories is of Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic. Don’t get too excited! There are no great details because Aunt Paula was 4 at the time.

“The only thing I can recall is people being excited at the dinner table, especially your father, who was 7,” she said. “I may be able to do better with other events. I clearly recall the crash of 1929 and my parents talking about people jumping out of windows and committing suicide after losing their life savings. Big shots selling apples. As it was, we were already in a poor financial state, but after the crash, we were in a disastrous financial situation.”

After he moved back in with me to the Lower East Side, my father once told me about my grandmother, Ida, chopping wood with an ax at a construction site being demolished in our neighborhood. Paula nodded, after taking a long sip of water. “It’s true,” she said. “For stoves that burn coal or wood. It was free if you chopped it. Around that time, we had to rely on home relief, and well, that felt awful for parents and children. I hated the clothes provided for us. Fortunately, Ima had run a sewing school back in Jerusalem when Abba was a yeshiva scholar and could make me dresses on her machine. Eventually, she returned to work managing a bridal shop on Clinton Street.”

Paula also remembers the time in the 1930s when Lindbergh’s baby was kidnapped. “A man named Bruno Hauptmann was accused of it, and it was a horrible situation,” she said. “We talked about it at the dinner table in Yiddish because it was so sad. Although he claimed not to have been involved, no one believed him.” She pauses for a second. “I saw Eleanor Roosevelt once! In the Lower East Side! Is that good?”

(You bet!)

In 1934, when Aunt Paula was 11, the long and skinny Sara Delano Roosevelt Park opened on the Lower East Side, stretching over four blocks. It was the largest park for children the city had ever built, and it was named after the president’s mother, the “First Mother,” who was about to celebrate her 80th birthday. Eleanor Roosevelt headed down there from her Upper East Side digs, dutifully representing her overbearing mother-in-law. Accounts from the time mention rows of schoolgirls dressed in white middy shirts standing at attention by basketball hoops and volleyball nets. (Two years later, a week before the 1936 election, there was a bigger gathering of 20,000 with the president there, but Paula was sure she was there at the first ceremony in 1934. I asked if it was Sara there then. “No! Eleanor.”)

Paula also remembers the radio crackling with static when she heard the news that Amelia Earhart had disappeared somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. “I was a big fan. She was so inspiring to all my classmates, and we followed the story until we gave up hope.”

As Amelia Earhart’s biographer, I am startled that she remembers this so well. I check my phone for the day of the week in 1937. Amelia Earhart disappeared on a Friday, and my now-very-secular family celebrated Shabbos then. That must have been another lively tenement dinner conversation over challah and brisket.

Litvaks don’t mess with nonsense, especially my family, who were once part of a stern scholarly group labeled the Misnagdim who doubted much of Hasidic interpretation. No conspiracy theories for them! “The government didn’t know what had happened, and we decided as a family that Amelia probably ended up underwater,” she said.

Paula and I moved on to talk about the end of the Great Depression.

“This is a painful time for me, Laurie,” Paula said. “I’m not exactly sure what year it was, but we had a home inspection at our house. Your father was bedridden after a terrible infection that spread, and your uncle Sol, who was so much older than us, had his own family to support. My parents had small-time jobs and I was old enough to work and add income to the family, and this stern woman told my family I had to get a job. I couldn’t attend City College (the midtown branch) during the day if we wanted to keep receiving money from the government. It was a big deal to get into the daytime college. Your grades had to be stellar, and I did well in school. My parents were very ashamed that I had to go through that disappointment. I now had to go to college at night and get a job during the day, which was not a positive experience. I worked as a teenage clerk in a button factory in the Garment District, on West 39th St., at a firm called Harlem-Adler.”

She admitted that she was furious at her lot but movies offered an escape from anger.

Paula’s favorite film star before and during the war was that blonde Adonis, Gene Raymond. In the war, he was even a decorated B-17 pilot. “The most gorgeous thing the world had ever seen,” one contemporary called him. Since 1937, he had been married to brunette movie star Jeanette MacDonald. She named her first son, Gene, after him. I was sucked into a deep Wikipedia read while fact-checking this part of our discussion, as I didn’t know anything about this forgotten heartthrob. Yes, Raymond was married to Jeanette MacDonald. Yes, he was a pilot. But did Aunt Paula know Jeanette MacDonald allegedly caught him in bed with drummer Buddy Rogers? While she was pregnant with Nelson Eddy’s baby? Who knew nearly-90-year-old gossip could be so juicy?

Several friends who heard I was writing about Paula asked if she remembered the Third Avenue El coming down in 1955. She couldn’t (she was living in Queens at the time, a stay-at-home mom), but Paula certainly remembered riding the elevated railroad in Manhattan as soon as she was able to do so.

“It was such a fun experience,” she said. “Sometimes, the train would circle around the curb, and I could peek into the windows of people living nearby. It could be a bit shocking!” She remembers babysitting for a young relative in the Bronx one time, and a station was closed, so she had to travel to Chambers Street, not her stop. It was after midnight, and no one knew where she was. “There was no texting! A police officer met me and escorted me to my home when I got out of the station. My mother had called the police.” (I laughed. My grandmother, born in the 19th century, Aunt Paula’s mother, was my ancient-looking babysitter in the 1970s. She did not play around!)

“I was 18 in 1941 when Pearl Harbor was attacked,” Paula told me. “Of course, everyone knows it was a surprise attack. We were diplomatically negotiating with the Japanese, and then suddenly, we were under attack. At least that’s how I remember it. Did you know that we were talking to them?” (I actually didn’t. That night I read more. In November, the Japanese prime minister proposed to Roosevelt that they meet in person soon, either in Honolulu or Juneau, Alaska, to discuss Japan’s war in China.)

“It was a Sunday, I think. My parents were upset to the point of tears. Because we had two boys in the family, they were patriotic but naturally concerned. We survived the war without losing our family members because one of them, your father, was too ill to be drafted. In fact, after an operation, your father spent six months in the hospital, and we thought he would never walk again. My family arranged for him to be listed 4-F (a draft classification for men deemed unfit for military service for physical, mental, or moral reasons). Your uncle Sol was too old to be drafted.

“But I served as a USO hostess at the ritzy Temple Emanuel on Fifth Avenue during the war. What an honor! A job application had to be submitted, and I had to dress nicely for an interview. I took the subway uptown several times a week and danced with the soldiers, many of whom were married or had girlfriends. Before they were deployed, this was a pleasant experience for them. The hostesses would flirt with them and have enjoyable conversations, but we weren’t allowed to date them. You had to be careful not to fall in love with a handsome soldier. We’d welcome them, serve dinner, and dance. Some asked, ‘Will you write to me?’

“While I abided by the rules, not everyone did, and believe me, I met some handsome soldiers. We all felt like we were helping the war effort.”

“It must have been tough to realize that some of the men you danced with didn’t make it,” I said, and Paula nodded.

“My grandchildren, so used to getting things instantly, are amazed that there were so many restrictions during the war. In those days, you couldn’t buy a washing machine, you couldn’t buy a phone, or you couldn’t buy lots of different things. We used ration cards to purchase certain foods, but only in specific quantities. Gasoline, butter, sugar, and many other things were limited, even milk and coffee. Nylon, silk, rubber, and tires were nearly impossible to find.”

I was extra curious about the stockings, as I had read silk stockings were unavailable during the war, so some people painted them on.

“Well,” said Paula, “I repaired any runs I had with a special gadget. A hole couldn’t be repaired, but a run could be, so I didn’t have to have them mended.”

And her hair? How did she wear it in the war years?

“After having a pageboy haircut as a child, I kept my hair short because it was easier to manage, and I didn’t look as cute with long hair.” But when the Andrews Sisters were ruling the charts, Paula used to go to the beauty parlor, and they would tease her hair to the skies.

Paula had teased hair when she turned 21 in May 1944 and headed to the polls for the first time to cast a vote in a presidential election.

She was a proud girl of the staunchly Democratic Lower East Side, and she pulled a lever for Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Recalling wartime brought back some painful memories during our meeting. “The most devastating global event in my lifetime was the Holocaust. How could this have happened? So many people were killed. Why, because one evil person wanted to get rid of them? Those who remember must bear witness. I find it inconceivable to believe anyone who witnessed what fascism could do to humanity could vote for Trump. Did you learn the lessons of the Holocaust? Trump’s idea of a good guy is Putin. That alone is appalling. I am a 99-year-old woman, and I know a few things, like right from wrong. I want my great-grandchildren to know where I stood on Trump.”

I am a 99-year-old woman, and I know a few things, like right from wrong. I want my great-grandchildren to know where I stood on Trump.

Next came a happier stretch of interview. Aunt Paula’s face broke into a smile at the memory of the favorite New York mayor of her lifetime, Fiorello LaGuardia. Paula described him as lovable. LaGuardia’s mother was Jewish, and his father was a lapsed Catholic turned Episcopalian. The short and paunchy LaGuardia (nicknamed the Little Flower) tried his best to serve as a father figure for anguished New Yorkers. During the summer newspaper strike in 1945, he was especially comforting. The traumatic war was almost over when he decided to read “Little Orphan Annie” and “Dick Tracy” as part of his regular Sunday radio newscast on WNYC. This was also a fun way to score a political point about the union letting New Yorkers down during need. And Mayor LaGuardia certainly read “Dick Tracy” enthusiastically. “Say children, what does it all mean? It means that dirty money never brings any luck! No, dirty money always brings sorrow and sadness and misery and disgrace.” LaGuardia’s signature phrase “What does it all mean?” was sampled by hip hop trio De La Soul in 1989.

Paula remembered that in 1940 LaGuardia cleared up all the pushcarts, and moved longtime sellers into the city-run Essex Street Market, with four buildings and 475 vendors. A swankier and hipper light-filled Essex Market complex across the street from the old WPA-era complex attracts a younger generation and is part of this legacy.

And an even better memory for Paula was the end of the war.

“Oh! People were so excited when we found out. It was possibly the greatest joy I ever experienced. I was at home with my family and heard the news on the radio about the crowds at Times Square. But it was almost as festive on East Broadway. We had this man downstairs on the street, sort of a loon, but he was walking up and down the street and yelling repeatedly. ‘The war is over! The war is over!’ Before you knew it, he had followers marching down the block with him, laughing and crying.”

“Things got better after the war, giving us a sense of peace,” Paula said. She laughed for a second before she explained. “As you could not get a phone during the war, we finally got one after it ended, but it was a troublesome party line. One phone line was shared by multiple people in different apartments! You couldn’t make a call if the other party was on the phone. You had to wait until your neighbor was finished talking before making your call. Not easy to believe now, I’m sure.”

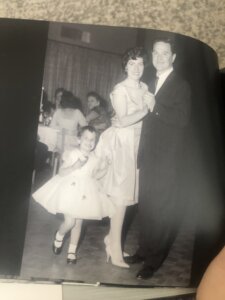

My svelte and fashionable aunt was married in 1948 to Sid Goldstein, a handsome would-be architect from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, who had been an air mechanic in WWII. They met at a political event held in her parents’ apartment when they were away for the day. “Sid and I got married at Broadway Mansion, a wedding hall across the street. I walked down tenement steps and across East Broadway in my bridal gown. At first, we lived in my parents’ place on East Broadway, and my son Gene lived there for his first year. It was challenging to get an apartment after the war. Still, eventually, we managed to find a cheap place in Queens, a starter apartment. I was often back on the Lower East Side to visit my parents, who eventually got a lovely co-op apartment through the Ladies Garment Workers’ union.”

(I live in that apartment now with my family.)

Paula remembers visiting her old neighborhood in the summer of 1953 when Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed. “The Rosenbergs lived in Knickerbocker Village, a middle-class Lower East Side complex where one of my childhood friends moved into when it first opened up in the 1930s. I felt sick thinking about the children they would leave behind. What were their children’s ages? Perhaps 6 and 10.” (A quick fact check on my phone confirmed my aunt’s guess.)

When Roosevelt died, we learned it on the radio. But with Kennedy’s death, we saw everything Jackie saw.

When Paula and I started talking about the 1960s, she had another flood of memories, especially on the day Kennedy was shot.

“All day long, we watched. Laurie, it was such a somber day,” she said. “When Roosevelt died, we learned it on the radio. But with Kennedy’s death, we saw everything Jackie saw. She was sitting next to him, and then when they had the funeral, with his small children saluting his dead body, that was very difficult to watch. But trust me, everybody was watching.”

Times were changing, and Paula’s look changed too; she was pretty stylish, but she kept up with more than just clothing. Silently, she supported her eldest son’s political protests, especially against the 1970 Kent State massacre. “Gene had to be careful, as he wanted to be a dentist and had applied to medical school. But he was so angry. And for good reason.”

Her most painful memory was when her husband Sid, an up-and-coming architect at I.M. Pei, died from lupus in 1970. Even today, it is not something she wants to dwell upon.

It was a crushing mental blow, and with four kids, a monetary setback too. As a housewife, she had taken the odd bookkeeping job. However, now a widowed mother of four, she used the college degree she had earned in night classes. She found full-time work at a Manhattan clothing company, Charles Greenberg and Sons. She started as a bookkeeper and worked her way up to a human resources manager.

Like many who have lost a life partner, darkness hit at odd times, and friends and family encouraged her to travel for a mental escape.

“The first airplane ride I took was a few years after my husband Sid died,” she said. “My first flight was on El Al to Israel. I visited where my parents grew up, in the extremely religious enclave at Mea Shearim. When I visited, it was a much more Orthodox neighborhood than when the Aba and the Ima arrived from Lithuania at the end of the 1800s. It was fascinating, and I met so many relatives. We had very little direct loss during the Holocaust because our family moved to Jerusalem at the end of the 19th century. Ever since then, I’ve been traveling. Meeting interesting people and venturing to far-flung places have helped keep loneliness at bay. I traveled to Russia, China, Spain, France, England, Wales and Scotland.”

She had been deeply in love with Sid and could not bring herself to date new people. Until she was in a better place, her children’s accomplishments would provide whatever joy she might have.

The second eldest of her three sons, Stuart Goldstein, then a student at Stony Brook, decided to take up squash in the early 1970s. My cousin “Stuie” had honed his quickness via table tennis and became one of the top squash players in the world and a minor celebrity. “I attended all of his games, of course. It was thrilling to be there. The speed, the power. It was wild. A new chapter in my life.” As an athlete’s mom, a favorite moment was when Stu beat the legendary ten-time North American champion, Sharif Khan.

The Forward recently profiled his daughter Dani G. Waldman, who also became a world champion athlete. In this year’s Tokyo Olympics, she was a showjumper.

Paula says she takes great pride in all of her four children. Gene, the dentist; Stu, who entered real estate after his athletic career; Eric, the architect; and her baby girl Cora, who became a children’s clothing designer and is now a grandmother herself.

“I consider my family the most precious thing in my life. I have four children, eleven grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren, so I have brought into this world 21 people. That’s a lot of people. A village.”

I was in the living room, and I had the TV on, and I saw the plane fly into that second tower

I have strong memories of my aunt in the 1980s when she was the walking nut I am now. Paula’s son Gene, the dentist, gave her a book about walking and she walked all over New York City back then, often strolling from her daughter’s apartment at 93rd Street to Penn Station.

We had talked a lot already, but my indefatigable aunt said she did not need a break. She was going strong by the time we got on to a new century and then 9/11. “I was in the living room, and I had the TV on, and I saw the plane fly into that second tower, and it collapsed. I saw it on TV. Wow, that was terrible. I think plenty of Americans remember that day without me rehashing it.”

She says she enjoys being connected to her grandchildren on social media, especially Facebook. “I keep up as best I can, and I certainly don’t mind all our progress in my lifetime. Of course, I love having my own telephone line and a refrigerator, air-conditioning, and TV. I even tried out that Wordle game. I think about the future, not the past, and I am excited about my 100th birthday ‘to-do’ my kids claim they are having for me.”

My aunt still manages to get her steps in every day. “Walking keeps me fit, and I have stayed vigilant about masks and vaccines as the pandemic lingers. I was just vaccinated again.”

Aunt Paula lost one of her two sisters from complications of COVID last year after she was stuck in an assisted living facility. “This might sound strange, but I miss fighting with Chavie. (My Aunt Eva’s Yiddish name.) We were very close. Even when we argued, it was just sisterly stuff. I wish I could speak to her every day. Fortunately, I have my baby sister, Esther, to call.” (Her “baby” sister, my equally vivacious Aunt Esther, is 91.) She shared her room with two younger sisters when living in a tenement.

I checked my watch, and we had been talking for four hours. I had to wind things up if I was hoping to catch my train back to Manhattan.

But I had one last question. And it meant a lot to me to ask.

“Go ahead!”

What was the most crucial lesson my aunt could impart to the Forward’s readers?

She didn’t hesitate.

“That protecting democracy is everyone’s job, including those who are better off and feel removed from humble beginnings. Democracy must be protected for our children, our grandchildren, and the future of our country. We all need to vote! Vote Democrat. Remember how poorly your family was treated as immigrants! Look at your privileged lives now. Empathize. Help, don’t hinder immigrants’ lives. Support a women’s right to govern her own body. Be kind.”