10 Jewish things you probably didn’t know about Superman

Yes, the man from Krypton’s creators were Jewish, but do you know which biblical figures he was modeled after?

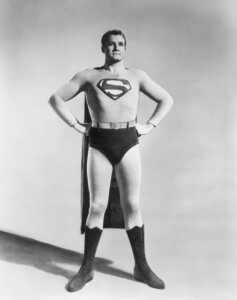

In June 1938, a caped crusader (whose outfit seen above was worn by Christopher Reeve) was born. Photo by Getty Images

It’s Superman’s birthday! The world’s first superhero debuted 84 years ago, in June 1938’s “Action Comics #1,” changing pop culture forever.

You probably know that Superman was the brainchild of two Jewish teenagers, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who borrowed elements from Jewish tradition and culture to create their character. Most famously, his Kryptonian surname “El” means “god” in Hebrew and his origin story is basically that of Moses.

But that’s just a schtickle. To celebrate the mensch of steel, here are 10 Jewish things you didn’t know about him.

- He was partly modeled after Samson

While the parallels to Moses may seem obvious, Superman’s co-creator Jerry Siegel doesn’t mention the biblical prophet in his unpublished memoir. The individual he does credit as a “strong influence” is Samson.

“Samson the Hero,” as he’s known in Jewish tradition, is famous for his superior strength. But he also had superior speed and could leap long distances in a single bound. And he was a judge: He fought for truth and justice.

In his early comics, Superman is repeatedly touted as “possessing the strength of a dozen Samsons.” In “Superman #2” (September 1939) he knocks down the support pillars of a great hall, proclaiming that “a guy named Samson once had the same idea!” And on the cover of issue #4 (March 1940), he topples columns to bring down the roof atop scurrying crooks. All of these, Siegel wrote, were deliberate homages.

- The Golem of Prague was a strong influence

In his memoir, Siegel recalls how he’d been increasingly frustrated with rising antisemitism in Europe and the U.S., and was “very favorably impressed by a movie called the ‘The Golem,’ about an avenging being who used his awesome strength to crush a tyrant and save those who were being oppressed.”

He was referring to the 1920 German silent film. It was co-written and directed by Henrik Galeen, who was Jewish and also wrote the first vampire film, “Nosferatu.” This was an international hit that also inspired 1931’s “Frankenstein” and “I, Robot,” “Blade Runner” and “The Matrix”.

Long before he was the Man of Steel, Superman was known as Champion of the Oppressed. He was an advocate for the New Deal, open immigration, British rearmament and intervention in WWII, and once the U.S. joined the war his comics essentially became regulation equipment for the 8 million service members who read them. Jeeps, tanks, boats and bombers were named after him and decorated with his image.

Superman was Siegel and Shuster’s avatar, fighting Nazis on the front lines: an indestructible, indefatigable protector fashioned into existence through language and art, made of paper and ink instead of clay.

- The Golem also inspired one of his best-known enemies

The legend of the Golem, especially the 1920 movie, was used for the origin of Bizarro in “Superboy #68” (October 1958).

One of Superman’s most famous and enduring adversaries, Bizarro is his doppelganger, created from “non-living matter” with orthogonal, claylike features and chalk-white skin. Despite good intentions he’s unruly and destructive, pacified only by a little girl who’s unafraid of him — an idea taken from “The Golem” and later used in “Frankenstein.”

- His publishers funded Jewish charities

The owners of DC Comics were Jewish immigrants from the Lower East Side, Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz (Yakov Lebovitz). Much has been said about how they acquired the rights to Superman along with the first story for just $130, bilked Siegel and Shuster of their due and ultimately fired them.

While they may have been scoundrels, they also cared for social causes, especially Jewish ones. Donenfeld spent much of his fortune helping found the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, along with other charities. Liebowitz was a trustee of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York and a founding trustee of Long Island Jewish Hospital, a member of its board and even its president from 1956–1968.

Whatever their motivation, the money Superman earned saving lives in fiction helped save lives in reality.

- His creators got into a personal tiff with the Nazis

On Feb. 27, 1940, Siegel and Shuster published a two-page comic in the magazine Look, titled “How Superman Would End the War.”

Almost two years before Pearl Harbor, the Man of Steel stormed through the Siegfried Line, twisted Nazi cannons into pretzels, punched the Luftwaffe out of the sky, grabbed Hitler and Stalin by the scruff of their necks and brought them to stand trial before the League of Nations.

The Nazis responded in the April 25 issue of Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps), the official newspaper of the SS, with a full-page tirade accusing Superman of being a Jewish conspiracy to poison the minds of American youth.

Several accounts attribute this response directly to Joseph Goebbels, who may also have had a conniption about it in the middle of a Reichstag meeting. Either way, it made the news in the U.S. The Bund sent Siegel and Shuster hate mail and picketed DC’s offices.

Siegel and Shuster never responded publicly, but they eventually did in “Superman #25” (December 1943). It’s a spoof featuring a superhero based on the Korps’ description of Superman, who’s infuriated the Nazis by constantly lampooning Hitler.

- His radio show actually was a “conspiracy”

“The Adventures of Superman” was the most popular children’s show on radio, airing a staggering 2,088 episodes from 1940 to 1951.

Jewish showrunner Bob Maxwell (Robert Maxwell Joffe) worked with the ADL to incorporate democratic and antiracist themes, enlisting other organizations like the National Conference of Christians and Jews, education consultants, journalists and even Margaret Mead. He called it “Operation Intolerance.”

The most famous of these “goodwill propaganda” storylines is “The Clan of the Fiery Cross.” It demystified and trivialized the Ku Klux Klan, using real secret code words and rituals supplied by undercover activist Stetson Kennedy. It reportedly caused a sharp decline in KKK membership.

- His ancestors were slaves who broke free

Elliot S. Maggin was Superman’s principal writer from the 1970s to the mid-1980s. His Judaism and studies of kabbalah and Martin Buber heavily influenced his work, and he acknowledged ascribing “effectively Jewish doctrine and ritual to the Kryptonian tradition.” That Superman is Jewish, he said, “is so self-evident that it may as well be canon.”

In “Superman #264” (June 1973), Maggin revealed that in Krypton’s ancient past they were enslaved by Taka-Ne, who, like Pharaoh before him, forced them to build his ziggurat fortress. They eventually gained freedom by orchestrating a plague of hives.

- He introduced the first openly Jewish superhero

Superman visited Israel in “Super Friends #7” (October 1977), where he met Seraph, the world’s first explicitly Jewish superhero. Seraph derives his powers from the cloak of Elijah, the ring of Solomon, the staff of Moses and long hair like Samson’s.

- His father Jor-El wanted Albert Einstein to raise him

When you’re the premier scientist on Krypton, it makes sense you’d want your child to be raised by the premier scientist on Earth.

In Maggin’s 1978 prose novel “Superman: Last Son of Krypton,” he revealed that Jor-El had sent a probe ahead of his son to find the world’s most developed mind to raise him. He chose Einstein, who humbly declined, instead helping make sure the Kents could find him.

- He’s still a nice Jewish boy

In the 1980 movie “Superman II,” when he saves a boy who tumbles into Niagara Falls, an old lady exclaims, barely audible in the melee, “What a nice man! Of course he’s Jewish!”

Neither Mario Puzo’s original script nor Tom Mankiewicz’s shooting script includes the line, most likely inserted impromptu by Jewish director Richard Lester.