A Neil Diamond show heads to Broadway. Just don’t call it a jukebox musical

‘A Beautiful Noise’ chronicles the superstar’s triumphs but doesn’t shy away from his struggles

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Four years ago, Neil Diamond and Bob Gaudio, two longtime friends and colleagues, were having a chat. Gaudio was one of the original Four Seasons and had produced six of Diamond’s albums. Diamond, who’d released his last album of original material, “Melody Road” in 2014, had seen “Jersey Boys,” the jukebox musical based upon the life and career of Frankie Valli and his Four Seasons mates. Diamond really liked it, and he was in the mood to look back.

“One day Neil said, ‘Hey, what about doing one about my stuff?'” recalled Ken Davenport, Gaudio’s friend and a two-time Tony winner himself. “And Bob said, ‘We can make that happen.’” And they did, with Davenport and Gaudio as co-lead producing partners of “The Neil Diamond Musical: A Beautiful Noise.”

Boston, then Broadway

The show is playing a pre-Broadway run at Boston’s Emerson Colonial Theatre through Aug. 7. It was supposed to open long before now, but COVID-19 knocked it off course. (And, actually, another wave of the COVID subvariant forced the company to scrap 11 of the Boston preview performances in June.)

But now it’s finally Broadway-bound. Previews start Nov. 2 and the opening is slated for Dec. 4 at the Broadhurst Theatre, directed by two-time Tony-winner Michael Mayer.

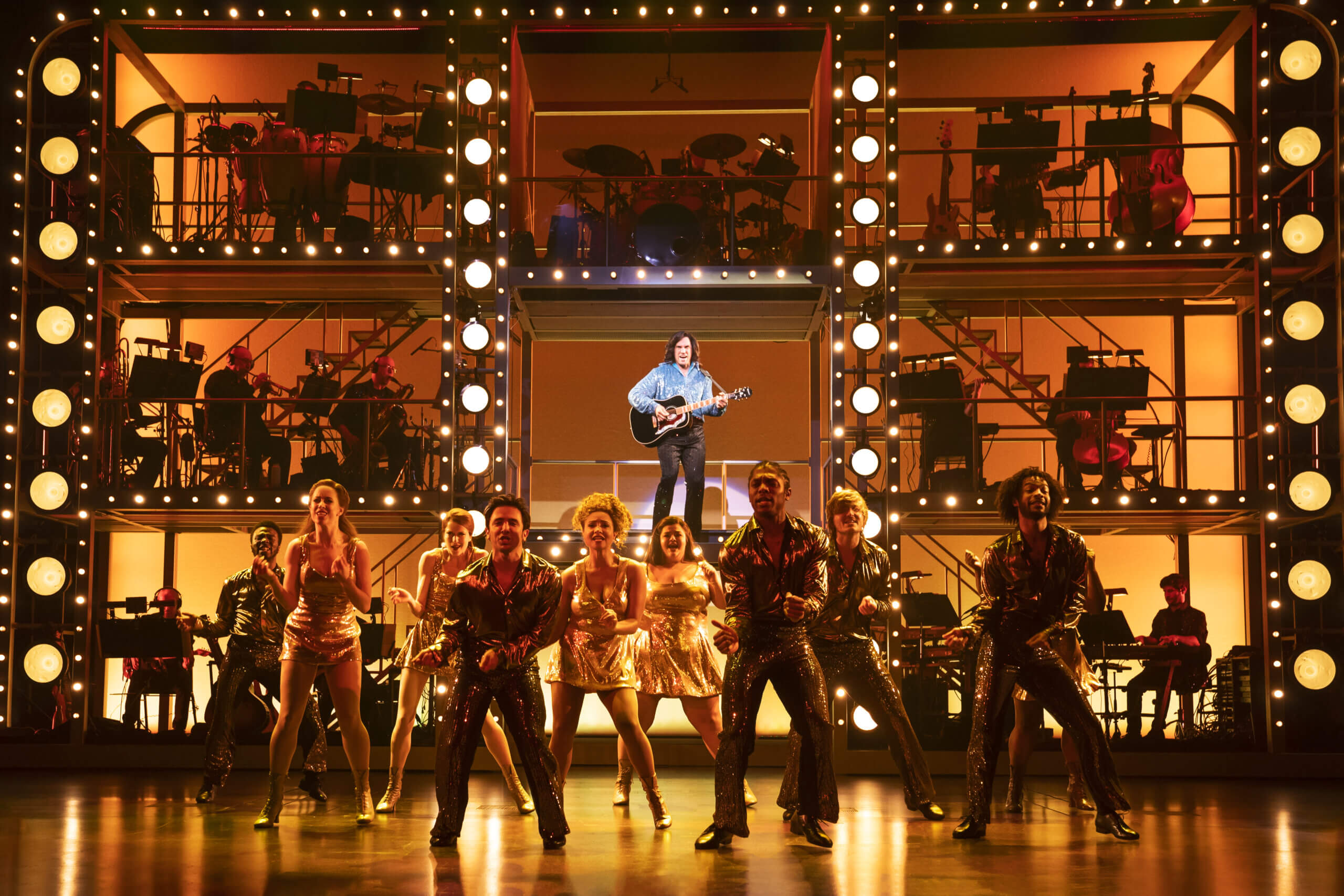

There are two Neil Diamonds in the show. Older, or current, Neil is played by Mark Jacoby, 75, and younger, performing-era Neil is played by an electrifying Will Swenson, 49. Yes, there are songs — plenty of them and they’re energetic and imaginatively choreographed. But the framework of the musical has a reluctant old Neil entering psychotherapy to unearth the roots of his long-simmering depression and low self-esteem.

‘This is a bio-musical’

Diamond, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2018, didn’t care for the designation of “jukebox musical,” which sounded vaguely dismissive and formulaic to him. Neither did Davenport.

“I don’t like that term,” said Davenport. “Here’s the thing: This is a bio-musical. We are using the songs to tell the story of his life. When we met Neil Diamond, he said he wanted to do a musical about his life with the music being the backdrop and the foundation. And also, when was the last time you went into a bar and saw a jukebox and it was all one artist?” The “jukebox musical” label “doesn’t make sense,” he added. “I don’t think the term qualifies for musicals based on preexisting catalogs.”

Before the curtain rises, there’s a fanfare, a big triumphant blast of Diamond’s music and a voice-over, introducing “The No. 1 recording artist in the world!” You expect to see the curtain lift and young Neil jumping right in, strutting his “Hot August Night” stuff, maybe opening with “Brother Love’s Traveling Salvation Show.” Nope. What happens is Jacoby and the therapist played by Linda Powell stare at each other in a terse, uneasy silence.

A psychotherapy journey

“This isn’t working,” old Neil grumbles. “I don’t like to talk about myself.” But Diamond’s reluctant psychotherapy journey is about to commence.

Soon, “A Beautiful Noise” becomes a weave of old Neil looking back at young Neil, sometimes ruefully, sometimes with pride, and young Neil pursuing his life and career. He’s rejected, then accepted; he starts to play in a New York folk club; he signs a record deal with a mob-run record company. He becomes hugely popular, tours for decades and still feels lonely. Then, he faces the declining years. There are marriages and divorces in that mix, too, and a fair amount of internal and external conflict.

“It’s all based on the conversations the book writer had with Neil himself,” said Davenport. “That was the process, with Neil and Anthony McCarten, who’s very well-versed in this type of material. He wrote ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ and ‘The Theory of Everything’ and he specializes in biographical drama, musical or otherwise. All the conversations came out of that. Neil read the early drafts and he helped to make it so that what we’re seeing is a real accurate portrayal of himself. What’s amazing about Neil is he showed it, warts and all.”

For McCarten, it was an easy decision to join the team: He grew up surrounded by Diamond’s music, the singer being one of his mother’s favorites.

The Jewish Elvis

Diamond, who is now 81, was a songwriter before he was a public singer. His “I’m a Believer,” covered by The Monkees, was the springboard to his career, but he thought he was too shy and reserved to perform. Eventually, though, dressed in sparkly, sequined costumes, he flipped that self-image around and became known as “the Jewish Elvis.” (“I love that expression!” said Davenport.) But the offstage depression, the “clouds” as Diamond put it, came back and hovered when the stage went dark and real life resumed.

One major attitudinal clash was with Neil’s first wife Jayne Posner (Jessie Fisher) who wanted to celebrate what he called “the little things” – i.e., the hits. He was always looking ahead to the “big picture,” unable to savor the success at the moment as it happened, fearing more moments wouldn’t come. And, as his fame increased — as his paid entourage swelled — Diamond found more comfort with his “road family” than his real family, a tension not unfamiliar to stars of his stature. When you’re loved by thousands night after night, how do you come home to only one?

The inspiration for his songs

If you didn’t know it before, you’ll learn during this musical that many of Diamond’s songs had deeply personal roots. “Coming to America” was sparked by his family’s emigration from Europe to America; “Song Sung Blue” was about depression; “Solitary Man,” about isolation; and “You Don’t Bring Me Flowers,” inspired by the deterioration of his second marriage to Marcia Murphy (Robyn Hurder).

Then, near the end, there’s the show-stopper, “I Am … I Said,” performed by both Swenson and Jacoby. That song came directly out of Diamond’s earlier therapy experience. In 2008, Diamond told MOJO magazine that it “was consciously an attempt on my part to express what my dreams were about, what my aspirations were about and what I was about.”

“When I first read the script,” Jacoby said, “my gut reaction was ‘This is a life, you’re just describing a life.’ You reach adulthood, your prime, and then there is a decline into the later years. Most people, whether they’re people of eminence like Neil Diamond or more ordinary people, for lack of a better word, that’s what happens. We’re not at our peak when we’re 80 years old and that’s a big thing for everybody, to accept declining strength, declining abilities. Everybody who reaches old age can say, ‘I can’t do that anymore.’ And even if it’s predictable — it’s normal, it’s understandable — it’s still ‘Oh my god, I can’t do that anymore!’”

A simple man, lacking in artifice

Diamond came to the first reading of the musical in January 2020, Davenport said, and gave them some notes. He watched video of workshops and saw rehearsals at points along the way.

For Jacoby, one of the more surreal or meta moments came in rehearsal, with the real Neil watching him play old Neil, who in turn was watching Swenson play young Neil. “It was unlike anything else I’d ever done or thought about doing,” he said. “It was very strange to sit down at the rehearsal hall in New York and sitting 8 feet away is the person you are playing.”

As for input, Jacoby said, the team got feedback from Diamond’s “camp,” though “not directly from Neil. There was indirect input as far as the specific actor is concerned. His current wife [and manager Katie McNeil] is more or less his caretaker and she conveyed to the creative team the ideas that she would like to see emphasized or de-empathized.”

Jacoby, who has a palpable gravitas onstage, says his learning curve was far different from Swenson’s. “Neil Diamond was his father’s favorite male singer and composer and Will had a pretty good Neil Diamond impersonation in his bag of tricks well before this project was even thought of,” Jacoby said. “His performance is driven.”

Jacoby was more of a fan of Broadway musicals than pop music growing up, and was only vaguely familiar with Diamond’s music. Yes, he knew “Sweet Caroline,” but says “I didn’t have encyclopedic knowledge of his canon. I watched a bunch of interviews and performances.”

When they met, Jacoby says he found Diamond to be “very personable, very nice to be around, a very simple man. I don’t mean simple as in limited intelligence. For all the gaudiness of the performance style he developed, he’s pretty simple, fundamental, lacking in artifice.”

A secular life

The Jewish aspects of Diamond’s life are in the mix, but “Neil has had more or less a secular life, ethnically speaking,” Jacoby said. “In reading about him and studying him, he doesn’t make a big thing about his ethnic Judaism. I don’t believe him to be religiously Jewish.” Emphasizing Diamond’s Jewishness, Jacoby added, “has not been discussed except for the context of what is actually in the script. I think that I’m Jewish enough that I don’t have to focus on it.”

What Diamond learns over the course of the show — his psychotherapy sessions interwoven with the belted-out songs and dramatic sketches — has to do with what Jacoby calls “a classic therapy thing – where you come to realize the influence of your origins, your parentage. … I may form relationships, I may have good times, but what I am is the influence of that, my parents.”

What’s likely to change between the out-of-town tryouts in Boston and the show on Broadway?

Probably not much. “There’s a line in the theater,” says Davenport, “that we’re never done because we’re live every night. So, we learn a lot. This is in the tradition of creating a musical. We listen to audiences and have our own instincts and we’re able to go back in the laboratory. But we’re very happy with the response we’re getting, how it’s working for us, and, frankly, Neil was very happy. The joke I’ve been saying is that when you’ve got a catalog like Neil’s, it’s not like we’re going to rewrite the second act.”