Jews need to start talking about — and shaping — the metaverse

A VR headset, a new book and its author help our columnist see the Jewish future

Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta, adjusts an avatar of himself during the virtual Facebook Connect event in New York on Oct. 28, 2021. A major theme at the annual conference was the company’s ambitions for the so-called metaverse, a new digital space that it believes will supplant smartphone apps as the primary form of online interaction. Photo by Michael Nagle/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Forward you are reading right now was born 125 years ago, when the primary language of American Jews was Yiddish, their main way of communicating was through the spoken or printed word, and their intellectual capital was Cincinnati.

There have been far-reaching, unpredictable changes in the world since then, and Judaism has evolved with them. But nothing — nothing — will reshape and challenge Jewish communal life in the next decade as much as something almost no one in the Jewish world is talking about: the metaverse.

I asked Matthew Ball, author of the much-acclaimed new book “The Metaverse,” how to get people to care about something that seems like far-off science fiction when there are so many things to worry about in the real world. In a very circa-20th century phone conversation, he answered in the straightforward, fact-rich way that makes his book such a compelling and convincing glimpse into the future.

“The world’s largest and most ambitious companies are focused on it,” he said.

Ball pointed to Microsoft’s $70 billion purchase in January of Activision Blizzard — the biggest big tech deal in history — to establish “the building blocks of the metaverse.” That kicked off a total of $120 billion in metaverse investments by private equity, venture capital and big tech firms in the first five months of 2022.

“If you want to positively affect or really even just affect the future,” he told me, “you need to be as aggressive in shaping it as those that are building it.”

In his book, Ball defines the metaverse as “a massively scaled and interoperable network of real-time rendered 3D virtual worlds.” He breaks down what that means, what technological advances need to take place to realize it, and how it will change business, education, entertainment, sex — you name it.

“Our lives will exist online,” he writes, “rather than just be put online.”

You may access this digitally built alt-reality through those opaque virtual reality dive-mask-like headsets. The metaverse will also come to exist alongside us with augmented reality — remember the Pokemon Go game that briefly consumed the world? — and as holographic-like conversations with people thousands of miles away, like Google’s Starline technology.

“Most of us believe that Zoom is more intimate than just a phone call,” Ball said. “But technology that is already here, just not widely available, further boosts that experience to the extent that for some it will truly feel like their pastor or rabbi is there.”

I know: weird. Even for a people long accustomed to talking about things they can’t see or even know exist — like, you know, God — wrapping our heads around the metaverse is a big ask.

That’s partly because the metaverse has largely developed through gaming platforms like Roblox, which 75% of children ages 9 to 12 in the United States used regularly in 2020.

But Jewish leaders tend not to be in the gaming demographic, and so all the opportunities and challenges of the metaverse — we’ll get to those in a bit — are a mystery to them.

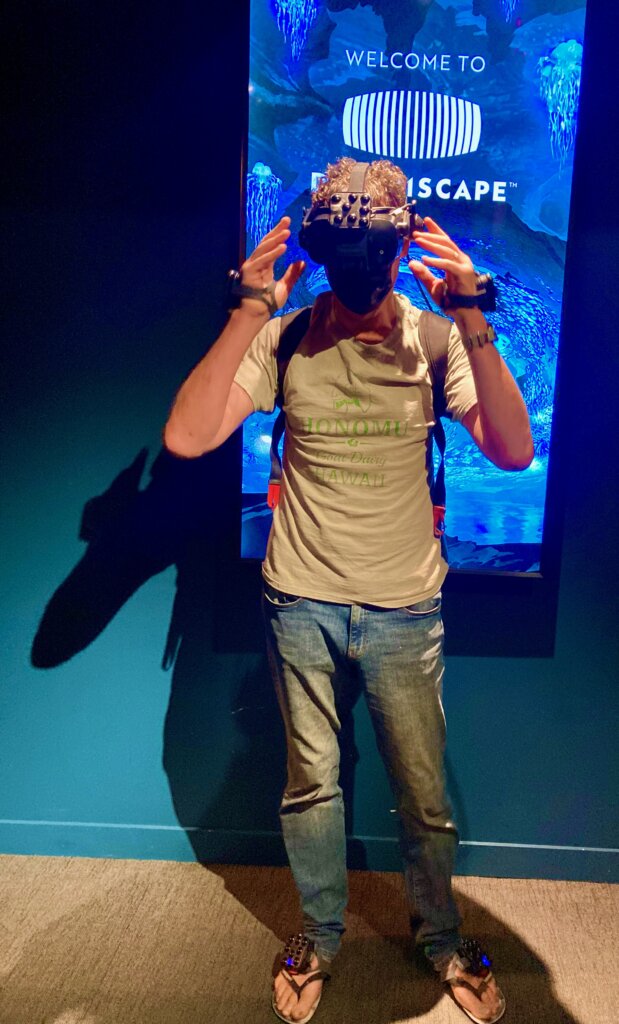

They were to me, too — I’ve never even used a video console outside of a game of Wii tennis. So before I spoke with Ball, I drove to the Century City Mall, paid $20, and walked into Dreamscape, a chain offering 15-minute VR experiences.

I donned that scuba-like mask and modules for my feet and wrists that looked a lot like phylacteries. These devices, meant to supply physical sensations, will be able to make us feel we are walking the streets of ancient Jerusalem, or holding a long-departed loved one or, yes, having sex. By 2028, sales of such devices are projected to more than double to $6 billion.

My devices transported me first to the headquarters of the Men In Black, then to a distant planet, where, dressed in a black suit and Raybans, I evaded an alien octopus using a flying scooter. By the time I “docked” — I hadn’t really moved three inches — my heart was pounding and I was, for lack of a better word, tripping.

Two days later, I returned to experience a deep-sea dive with blue whales. If movies demand the willing suspension of disbelief, the VR experience requires the constant assertion that what feels real really isn’t.

When I told Ball how powerful the experience was, he wasn’t at all surprised. Ball, who is Catholic but grew up in a very Jewish neighborhood in Toronto, offered up the possibilities of a Jewish metaverse where a 90-year-old man who always wanted “to go on a Birthright trip” could, as could someone with severe disabilities. In the metaverse, congregants could gather from around the world to look one another and their rabbi in the eye.

“The truth of the matter is that for many, just reading scripture is transcendent,” he said. “The addition of new senses of visualization, of being able to share that experience at any time, from anywhere, with other people — I absolutely believe that that can add to what is already a transcendent experience.”

These are some of the upsides of the very virtual future, but there seems to be little communal interest in exploring it. In 2017, when Moment magazine asked 16 Jewish scholars and leaders to predict what the Jewish community would be like in 2050, not one mentioned the metaverse.

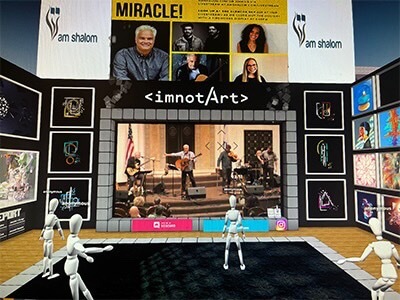

By not thinking about the metaverse, these leaders aren’t ignoring the elephant in the room; they’re ignoring the room. The Forward reported in March that just two congregations have so far made the leap into the metaverse: Am Shalom, a Reform congregation in the Chicago suburb of Glencoe, and the Brooklyn-based Chabad Lubavitch movement, which is constructing the MANA Jewish Center in an entirely virtual space called Decentraland.

Rabbi Steven Stark Lowenstein of Am Shalom purchased VR headsets for 18 staff and temple members so they could experience a virtual Seder together. “It was great fun,” Lowenstein said, “and sent a message that VR is real.”

This is, you understand, crude, early stuff. Ball steadfastly resists predicting when the metaverse will be a parallel fact of life. But he quotes many experts who suggest that by 2030 — a geologic era in tech time, but only eight actual years — those who want can live there.

Mark Zuckerberg predicted it’s five to 10 years out. He just reorganized the company formerly known as Facebook, renaming it Meta and making, as Ball told The New York Times, “an existential bet on where people over the next decade will connect, express and identify with one another.”

That, of course, will bring its set of problems. Every challenge we face in the 2D internet, including misinformation, hate speech and radicalization, will be worse in 3D.

A world where you can sit and talk to long-dead Holocaust survivors about their experiences is also a world where those same virtual survivors could declare the whole thing was a hoax.

Working with companies like Meta and government regulators to figure out new rules and explore the inevitable downsides of the metaverse seems like a smart use of Jewish communal resources for something that will be both inevitable and huge. Hate speech and disinformation were already baked into social media and Web 2.0 by the time the Anti-Defamation League and other groups developed a proactive approach to holding social media and other platforms accountable.

Those are the looming negatives, but there are plenty of positive reasons to start delving into the metaverse now: How about, for starters, the ability to mold Jewish education, culture and practice for the next 125 years?

Why wait? If the Jewish future will be shaped by the metaverse — and it will — it makes sense to help shape the future of the metaverse.