How a deadly disease saved Jewish lives and fooled the Nazis during WWII

‘Syndrome K,’ the subject of a new documentary, was highly contagious and highly fictional

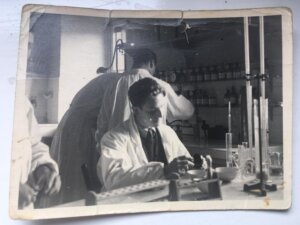

The ‘Syndrome K’ hospital unit as seen in 1944. Courtesy of Freestyle Digital Media

Director-composer Stephen Edwards says he is drawn to “ordinary people doing extraordinary things.” So, when he came across the virtually unknown story of “Syndrome K” and the Italian doctors who concocted this wholly invented disease in order to save Italian Jews during World War II, he knew he had to explore the topic further.

Co-directed by Greg Hunger, “Syndrome K” begins in the fall of 1943 as the German soldiers invade Italy, rounding up and shipping thousands of Jews off to concentration camps. Jews were already ghettoized and faced an array of antisemitic humiliations and daily restrictions, but nobody was prepared for the horrors that followed.

Hospital as safe haven

Some fled to the 450-year-old Catholic-run Fatebenefratelli Hospital set on a teeny island in the middle of Rome’s Tiber River, just across from the Jewish ghetto on one side and the Vatican on the other. The Catholic hospital, under the leadership of anti-fascist Dr. Giovanni Borromeo, had a reputation as a safe haven for Jews and other anti-Fascists. This made it possible for Jewish physicians like Vittorio Sacerdoti to work as a doctor in that hospital, providing him false documentation. Outside its walls Dr. Sacerdoti was forbidden to practice medicine.

In the institute’s basement, Dr. Borromeo installed and hid an illegal radio transmitter and receiver that were employed to communicate with local partisans.

Working jointly with anti-fascist activist Dr. Adriano Ossicini, Dr. Borromeo and others came up with an ingenious plan to conceal Jews in the hospital by claiming they had “Syndrome K,” a degenerative, disfiguring and highly contagious disease, which in fact did not exist.

Nazis steered clear

Fearful of contracting the fatal illness, the Nazis largely steered clear of the hospital in general and the “K” ward in particular, though the patients were encouraged to cough their heads off if and when the Nazis were on the premises.

Dr. Adriano Ossicini, who was 96 and living in Italy when he was tracked down for this documentary, takes credit for coining the moniker “Syndrome K” in honor of Albert Kesserling, the German commander overseeing Rome’s occupation, and SS chief Herbert Kappler, who had been appointed city police chief.

Had the SS gotten wind of the doctors’ activities they would have been tortured and/or killed. They were indeed violating the mandates of the government and the Vatican. Still, some of the doctors’ closest confederates in and out of the hospital were friars and priests. In the end many Jews were saved, though precise numbers are not known.

Two surviving doctors, interviewed

The film’s central subjects are the two surviving doctors Sacerdoti and Ossicini; Giovanni Borromeo’s son Pietro recounts his late father’s recollections. Other Italian Jews who lived to bear witness provide their own memories, in addition to Suzanne Brown Fleming of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, who offers commentary. Narration was provided by Ray Liotta in his final film (he died this past May).

The doctors are remarkable figures who displayed extraordinary bravery. Yet regrettably they never fully come alive as three-dimensional human beings. How did they evolve to become the great moral saviors that they were? Giovani Borromeo is justifiably honored at Yad Vashem. It’s unclear if others are recognized there as well; they certainly deserve to be.

Production values

Part of the film’s problem is that in an effort to create historical backdrop and place the narrative in a broader context — the role of the pope and the church, the bonds and conflicts between Italy and Germany, the activities of the allies — the filmmakers lose their focus. Though individual sections hold interest, a lack of cohesiveness is pervasive.

In addition, some of the production values can seem tacky. Interspersed with the interviews are familiar archival footage and re-enactments, which cheapen the piece. Intermittent animation, a trendy cinematic device that is frequently incoherent and intrusive, feels more so here.

And the dubbing — or what appears to be dubbing — doesn’t help. At times, we hear Italian-accented English that is out of sync with the moving mouths of the interviewees. In one puzzling snippet, English subtitles appear beneath an English-speaking pope.

The church and the pope

Still, the film is worth seeing. I was especially intrigued by its discussion of the church and Pope Pius XII, who helmed the Vatican during this period. To this day, he’s a source of controversy over his silence on the treatment of the Jews. Some accuse him of being complicit with the Nazis. Others interviewed in the film, including surviving Jews, say that the pope was in a moral and political quagmire and had no choice other than neutrality and diplomacy.

The most pertinent question the film raises, however, remains unaddressed: To what degree was the pope truly ignorant of the hospital’s subversive activities — or did he just turn a blind eye?

“Syndrome K” casts a new light on an old conversation, while opening up another. It’s a story that needed to be told — if only it had been told better.