How Jews have confronted the seemingly eternal scourge of hatred

Two new exhibits in New York grapple with the ravages wrought by antisemitism

“The Holocaust: What Hate Can Do,” at New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage shows the destruction of once-vibrant Jewish communities. Photo by John Halpern

I learned what hate can do on March 9, 1977, when I went to work as usual that morning at the Jewish service organization B’nai B’rith in Washington, D.C. By lunchtime, I had become one of the more than 100 hostages seized and held there for the next 39 hours by an armed group of Hanafi Muslims. During that time, we were harangued with nonstop anti-Jewish rants by group leader and head hostage-taker Hamaas Abdul Khaalis.

Wielding a machete, Khaalis threatened to cut off our heads and throw them out the window. His accomplices had rounded us up at gunpoint, then forced us to climb the steps to the cavernous top-floor space still under construction. With bloody injuries inflicted by the gunmen visible for all to see, we sat on the concrete floor and listened in terror as Khaalis not only warned us that nobody promised us tomorrow, but urged us to pray to whatever God we prayed to.

That I am here to tell the tale is thanks to the lengthy negotiations that led to our release. That I feel compelled to continue to repeat this tale, all these years later, is testament both to the tenacity of hate, and to the short-term memory span of too many American Jews who prefer to regard each new violent attack against Jewish communities — in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill, the Colleyville synagogue in Texas, and elsewhere — as individual wake-up calls rather than an ever-more insistent alarm bell.

This experience has served as my personal motivation for writing so many articles over the years focused on fighting prejudice, fostering cooperation, teaching tolerance — and reviewing exhibitions like two that recently opened in New York.

“The Holocaust: What Hate Can Do,” at New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage and “Confronting Hate 1937–1952” at the New York Historical Society invite, if not compel, us to wrestle with how to grapple with the omnipresent violence fueled by prejudice we hear about daily and sometimes experience ourselves.

The visitor enters the new core exhibit at the Museum of Jewish Heritage through a spooky, tunnel-like corridor backlit by antique photographs and film reels from the first half of the 20th century depicting family and communal scenes of the once-thriving Jewish communities of Europe and northern Africa. Then, just as you approach what looks like a light at the end of this tunnel, you see the wall text: “Many of these Jews were murdered by April 1943.”

At which point it’s not only the contrasting brightness of the exhibit hall you’re then thrust into that makes you blink; it’s being cast into the Nazi maw, circa 1943, through immersive photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto, artifacts from the Auschwitz death camp and surviving possessions of the millions already murdered.

As in a film — or nightmare — flashback, we dive into the next gallery which makes us understand the depth and breadth of what the Nazis wanted to destroy, through a comprehensive retelling of the history, culture and religious traditions of the Jewish people from ancient times onward. Yet that is only prelude to the galleries that follow, filled with the equally long historical trajectory of antisemitic violence.

It’s a draining journey even before we reach the ascent of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler as head of the German government in 1933. Through newsreels, photos, letters, video memories of survivors, and the memory-laden personal belongings (a bracelet, a shirt, a drawing) that remain, the exhibit chronicles the year-by-year escalation of hatred, persecution, violence and mass murder perpetrated by the Nazi regime. You arrive grief-stricken at the end of the 12,000-square feet and two full floors of exhibition space.

The historical qualities are excellent and the visual materials both vivid and effective. This is what hate can do, the exhibit tells us — annihilate millions of people who did not conform to Hitler’s Aryan standard; obliterate the infrastructure of Europe; destroy whole towns and cities; and wipe out the sense of history and cultural continuity for so many Jewish and other communities that had once lived in the lands Hitler overran.

Most of all, the exhibition impresses upon us why and what we must remember. But because it abruptly stops, with the formation of the State of Israel in 1948, it also feels incomplete, leaving us with unanswered questions about what we can do in the present to halt the continuing spread of hatred.

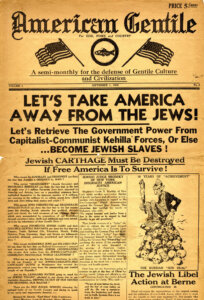

More successful in that regard is the New-York Historical Society’s exhibit “Confronting Hate: 1937-1952,” which explores the wide-ranging media campaign launched on the cusp of World War II by the American Jewish Committee (AJC) to beat back rising levels of American antisemitism along with all forms of bigotry.

The exhibit, organized in collaboration with the AJC, packs a powerful punch — literally. It starts with a vibrant poster from 1937 by German-Jewish illustrator Eric Godal depicting a powerful, angry worker swatting away the swarm of nasty stinger-bees, each one named for a particular prejudice: “anti-Jewish,” “anti Negro,” “anti Catholic,” “anti foreign born,” “anti Protestant,” “anti labor union.” “Swat Them all!” the caption reads.

With each angry insect bearing a swastika, it was also a call to resist Nazi ideology, even before America entered World War II.

Richard Rothschild, the advertising executive tapped by AJC to lead the campaign “believed these hatreds were anathema to America,” said Charlotte Bonelli, director of AJC’s Archives & Records Center.

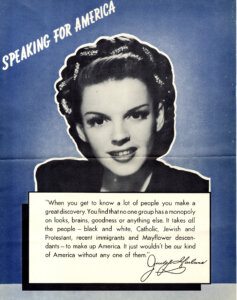

The AJC commissioned posters, comic books, pamphlets, newspaper cartoons and magazine ads, many of which are displayed here. AJC also formed alliances with numerous groups, including labor groups, the Citizens Committee on Displaced Persons, American government departments, women’s groups, educational associations, religious groups, and even celebrities such as Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra who participated in anti-prejudice ad spots.

Judy Garland’s smiling photograph graces a signed message that reads, in part: “When you get to know a lot of people you make a great discovery. You find that no one group has a monopoly on looks, brains, goodness or anything else. It takes all the people — black and white, Catholic, Jewish and Protestant, recent immigrants and Mayflower descendants — to make up America.”

“The exhibit illustrates the ways that new technologies were utilized then” and suggests that the newer technologies of today are waiting to be used, said exhibit curator Debra Schmidt Bach.

Bonelli and Bach both say that they hope the exhibit will spark ideas for educators, community leaders and others to foster dialogues and programs to fight prejudice. “One of the biggest things we can learn is these are not just dialogues from the past,” said Bach. The exhibit presents “an opportunity to think about how we can continue the conversation today.”

Well, then: Based on AJC’s work in the past, I suggest several possibilities for the future. First, let’s return to AJC’s message that prejudice against and intolerance of others is downright un-American, and rally anew around the words of our first president, George Washington, who in 1790 declared that our country would give “to bigotry no sanction.” Just how patriotic is that quotation? Washington’s letter is on display across the street from the Liberty Bell and around the block from Independence Hall, at the Weitzman National Museum of Jewish History in Philadelphia.

Second, let’s focus on social media, which in recent years has become a major breeding ground for hate speech, hate groups and possible hate crimes. Perhaps Sheryl Sandberg, former chief operating office of Facebook/Meta, could lead the charge. That she has fallen from grace of late does not negate her vast expertise in new media. Indeed, embarking on such a venture would provide her with a way to redeem her reputation by starting the clean-up of the vast swamplands of the hate engulfing cyberspace.

Finally, I put forward this motto for us all to contemplate: To confront hatred is to repair the world. It’s a tough job, but if we don’t, who will?

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 2

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 3

News School Israel trip turns ‘terrifying’ for LA students attacked by Israeli teens

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion This week proved it: Trump’s approach to antisemitism at Columbia is horribly ineffective

-

Yiddish קאָנצערט לכּבֿוד דעם ייִדישן שרײַבער און רעדאַקטאָר באָריס סאַנדלערConcert honoring Yiddish writer and editor Boris Sandler

דער בעל־שׂימחה האָט יאָרן לאַנג געדינט ווי דער רעדאַקטאָר פֿונעם ייִדישן פֿאָרווערטס.

-

Fast Forward Trump’s new pick for surgeon general blames the Nazis for pesticides on our food

-

Fast Forward Jewish feud over Trump escalates with open letter in The New York Times

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.