The Holocaust bus tour that was truly a trip to hell (snack bar included)

When Jerry Stahl’s life felt like it was collapsing, a visit to the Nazis’ most infamous concentration camps helped him find clarity

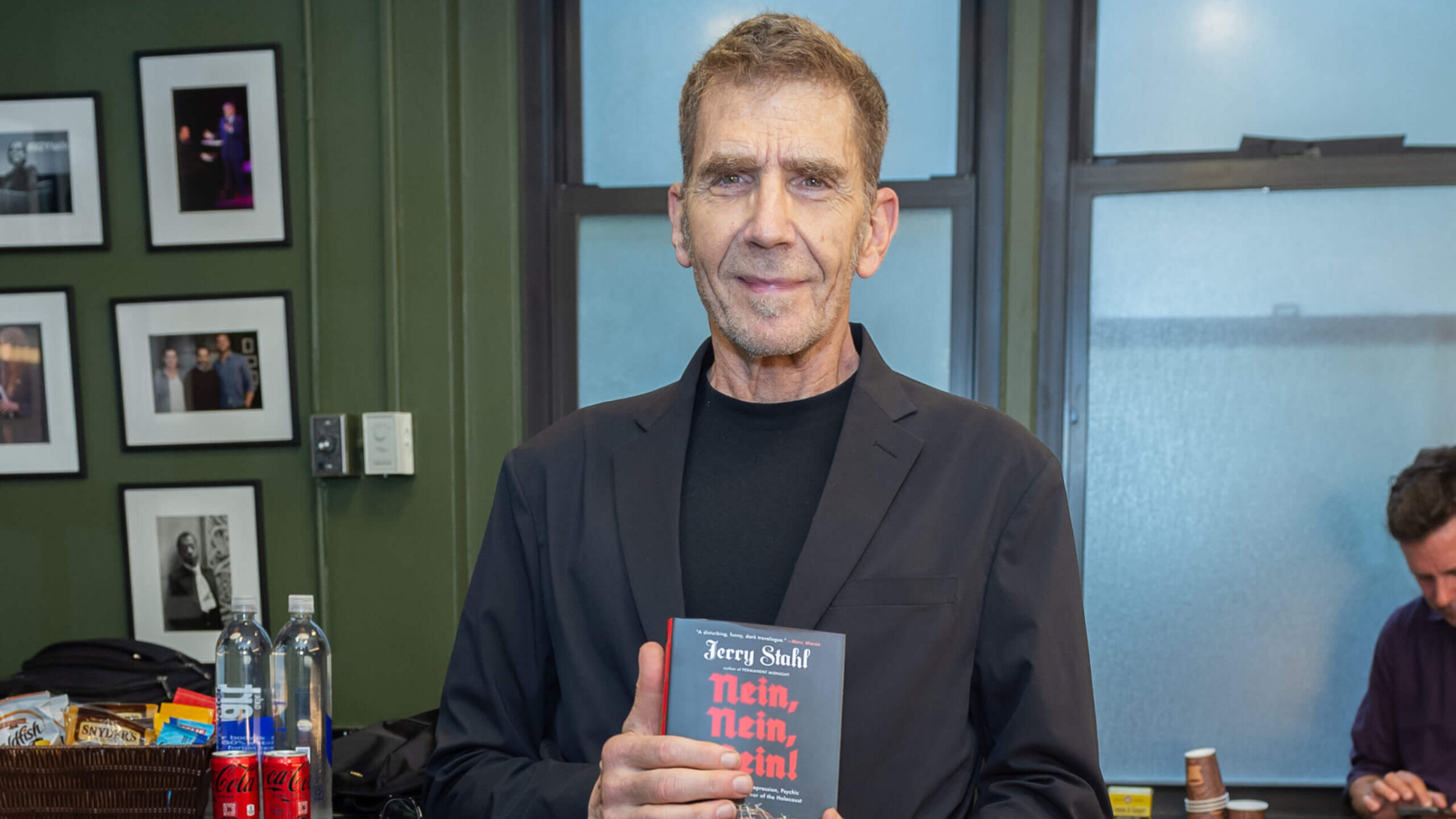

Jerry Stahl promoting “Nein, Nein, Nein!” at The 92nd Street Y. Photo by Mark Sagliocco/Getty Images

Editor’s note: This article contains discussion of suicide.

Jerry Stahl was on a bus tour of what he calls “Naziland” — three concentration camps and related museums in Eastern Europe — six years ago when his understanding of how the world perceives the Shoah did a somersault.

Stahl, the 68-year-old author best known for his 1995 memoir “Permanent Midnight,” knew he’d be trodding upon, as he said in an interview, ground “where the bones of the dead are buried and ashes had drifted.” He had some inherent trepidation, and expectations of somber reflection.

“My heart is open. I’m one big emotion waiting to happen,” Stahl said on the phone from his home in Los Angeles. “Who do I think I am to think I can grasp the enormity of this suffering and honor it?”

Yet grasping that enormity is precisely what Stahl tries to do in his new book, “Nein, Nein, Nein!: One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust.” The account contains a crazy quilt of emotions captured with dark humor and keen insight.

The book, Stahl said, is a chronicle of what he felt on the trip — “as a human, as a Jew, as a man, as a citizen of the planet.”

What it isn’t — at least, not always — is an account of the somber reflection Stahl expected. The first thing he saw in Auschwitz, he said, was “a guy in an ‘I’m With Stupid’ T-shirt slamming a Fanta and stuffing his face with pizza.”

“I just wasn’t ready for it. I don’t know why.”

So, it wasn’t the historic horror that struck him first. It was the mundane nature of people doing what people do in their day-to-day lives, no matter where they are. They eat, drink, crack bad jokes, respond in almost comically inept ways to their circumstances. Three Filipina girls who spotted Stahl became convinced that he was Michael Richards — the actor who played Kramer in “Seinfeld” — and kept yelling “Kramer!” because they wanted a selfie with him.

He let them snap the picture.

“I agreed to do the most grotesque thing you can do, especially in a death camp,” Stahl said of the selfie, “but I think there is a certain human truth” to people acting that way.

While Stahl took his trip in 2016, he only wrote about it during the 2021 pandemic-driven lockdown. Stahl faced serious roadblocks in finally beginning the book. He had lost many of his notes from the tour, and there were continual distractions from other projects — mostly failed projects — for TV, film and print.

And the subjects he planned to write about were challenging to revisit. As he writes in “Nein, Nein, Nein!,” he was not in a good place before taking the trip. He felt his career had run aground. His third marriage was in tatters.

He peered into the abyss — or more precisely, looked down from a bridge in Southern California. He “was discouraged from doing it,” he writes, when he realized he’d have to climb a fence and likely be caught by the suicide-prevention mechanism he described in our interview as “these weird chain-link macrame large-enough-for-a-human-being bags.”

“There’s a lot of athletics involved,” Stahl said. “They make it hard. I would have been News at 11 — ‘World’s Biggest Baby Caught in a Net, Swaddling.’”

So, Stahl said he thought, “Why not go somewhere where complete and utter despair and depression is wholly appropriate?” Like Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Dachau.

Another factor in his decision: Donald Trump was ascendent, and more than a few people were equating Trump’s tactics and autocratic bellicosity with Hitler’s. “With Nazism on the rise here,” Stahl said, “it was almost like, ‘Why sit here and watch the previews? Why don’t we go to where it happened and where it was shot?’”

The book examines how Stahl’s own personal demons collided with the ghostly demons of the Holocaust, with a dose of absurdity added by his being on a tour with mostly Midwestern tourists — early on the journey, he likened it to a 4-H Club trip — complete with a forced, though not entirely unwelcome, camaraderie.

He told his tour guide, Suzannah, and his fellow tourists that he planned to write about the trip. “I made the decision to be straight up about that,” Stahl says. “Being a writer, you’re a little bit outside the main community. Everybody can take you aside and tell you their deepest and darkest. As cornball as it sounds, I grew to love these people at the end.”

Part of what makes “Nein, Nein, Nein!” an engaging read are Stahl’s (sometimes) purposeful digressions. Some of these are whimsical, but all are pointed, like one about little salt-shaker-sized “Lucky Jews” — statuettes of rabbis clutching coins sold at Warsaw gift shops. The idea: Place one at the door so money won’t leave the house.

“In Poland, we have a saying: ‘A Jew in the hallway — a coin in the pocket,’” the shop owner told Stahl.

“I take six,” Stahl writes. “Because — why not?” Yes, they’re a racial stereotype, but in Stahl’s eyes, compared to the range of offensive depictions of Jews, “these rabbi dolls feel almost benign. All Talmudic beard and soulful eyes. But maybe benign is more insidious.”

There are gruesome details about the Nazis’ ingenious forms of torture and Josef Mengele’s “medical experiments.” There are stomach-churning accounts about Ilse Koch, “The Bitch of Buchenwald,”who used her victims’ tattooed skin and body parts for “crafting.”

As to experiencing the camps themselves, Stahl notes the contrast in presentation of the museums at each. Though the high-tech, immersive exhibition at Dachau is more informative and far-reaching, he writes, for him it had a less powerful effect than the silent horror of Auschwitz.

Stahl also realized that being overwhelmed by an experience can also leave you underwhelmed. “I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t aware of ‘bodies piled up in mounds,’” he said, citing Lou Reed’s song “Heroin.” “Through no fault of its own, these images are so numbing and so overwhelming.”

At one point late in the trek, Stahl found himself getting “burned out on the concentration camps,” he writes.

“I’ve become the weird guy who doesn’t talk much on the bus. I try to front that I’m gripped by the torment, soul-savaged by the in-your-faceness of strolling down the landscape where Hitler ripped the world apart, like a child tearing the head off a doll.”

In the end, Stahl attempts to step back from the statistics and the stock images of the Holocaust to cast an eye on the lives of its victims, and what they may have been like before Hitler came on the scene. He considers how terrifying it must have been to have their ordinary lives stripped away — “the futility of all those wasted hours thinking about sex and money, did their hair look right, success and failure and all the things that drain the life out of life — when life is so fucking vulnerable and fragile and easy to pluck away?”

With a book so stark and revelatory — as is pretty much anything Stahl touches — one wonders, what didn’t make the cut? Are there worse, more self-denigrating points not in print?

“The eternal question,” said Stahl, with a laugh. “I think that answer’s going to go to my grave, but I don’t know if there’s much worse than what is actually in there. If I think about it too much, I will start pulling back, which for my purposes wouldn’t ring true.

“To bring up another great Jewish writer, Bruce Jay Friedman — he said, ‘If you write a sentence that makes you squirm, keep going.’ Somehow, I squirmed my way through this book.”

Stahl has got two more books and another movie project in the works — in addition to a possible film adaptation of “Nein, Nein, Nein!” which has been optioned by Robert Downey, Jr. — but fears talking about them may be a detriment to doing them.

“At my age, I’m a lot closer to a man being dead than being 40,” he said, “so I’m writing like a man being chased.”