He preserved Ukrainian Jewish culture — before, during and after the Shoah

Elena Yakovich’s ‘Song Searcher’ examines how Moyshe Beregovsky recorded Yiddish folksongs and oral traditions

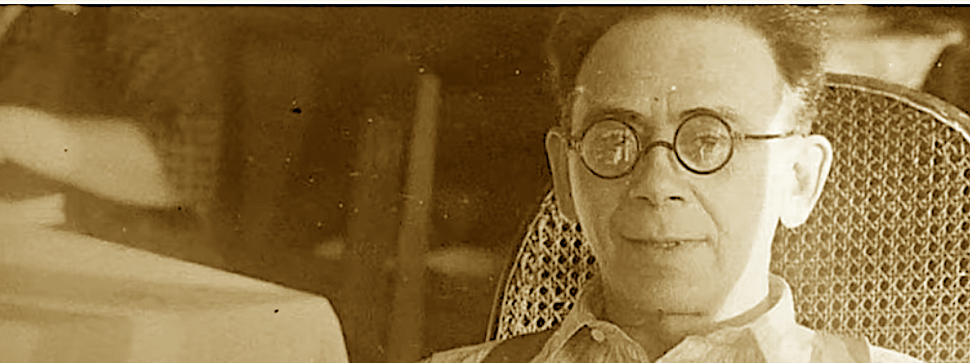

Moyshe Beregovsky. Courtesy of Songsearchermovie.com

In the late 1920s, ethnomusicologist Moyshe Beregovsky began traveling to Ukrainian Jewish villages equipped with a phonograph and wax cylinders. He was out to record wedding songs, klezmer anthems and lullabies. He couldn’t have known it at the time, but what he ended up documenting was a culture on the cusp of oblivion — and one that, against all odds, would continue a tradition of song.

Beregovsky’s archive, a collection of over 1,000 phonograph cylinders containing oral traditions, the voice of Sholem Aleichem and a vast catalog of songs from before, during and after the Shoah, was believed lost for decades, broken or perhaps plundered by the Nazis. But in 1990, the collection turned up intact in the basement of an academic building in Kyiv. In 2019 the songs formed the basis for the Grammy-nominated album “Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of World War II.” Beregovsky’s life is also the subject of the new film “Song Searcher,” now making the rounds at Jewish film festivals.

Directed by Russian documentarian Elena Yakovich, “Song Searcher” is a gripping history told through music, archival film and interviews with musicians, historians and Holocaust survivors. Yakovich followed the path of Beregovsky’s expeditions throughout Ukraine, stopping by memorials in towns now largely free of Jews, where the folklorist and composer recorded songs recounting massacres and invasions that occurred there throughout the 1940s.

Since filming in Ukraine, Yakovich has been seeing many of the same places in the news, now under siege by a different army. “This film became much more actual in two years, unfortunately,” she said in a Zoom call.

Moses Beregovsky’s missions began as part of his work with the Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture in Kyiv. Though the Institute was closed by Soviet authorities in 1936 and, years later, the tumult of war decimated the communities Beregovsky recorded, his work was far from over. There were new songs to seek out, with names like “Babi Yar,” “Shkita” (“slaughter”) and “Tulchin,” for a town where Jews were “torn to shreds.”

While these songs — some digitized for the first time for Yakovich’s film — offer testimony, survivors tell of their own experience. One, Grigory Shmulevich, remembered Beregovsky’s team recording his mother. Yakovich said Shmulevich, who in the 1940s survived a killing squad in Zhabokrich, had a health scare near the memorial there.

“I was standing on my knees and praying to the Jewish God,” Yakovich said. “I was praying and asking Him not to let this person die near the place from where he survived.”

During production Yakovich was often surprised by the music Beregovsky recorded nearly a century ago.

In one scene, unprompted, Igor Polesitsky, the Kyiv-born founder of the Klezmerata Florentina ensemble in Florence, Italy, plays his violin at the memorial in what was once the Jewish settlement of Kalinindorf, where most of his family was murdered. He knew the tune, and that it came from the Kalinindorf, because Beregovsky recorded it there.

“I don’t feel as if my violin is being played by me,” Polesitsky says in the film.

In August 1950, Soviet authorities arrested Beregovsky under charges that he was a “Jewish nationalist,” and he was sent to a gulag. His granddaughter Elena Baevskaya kept his correspondence, and reads from it in the film. Many of the letters request his family make copies of sheet music and send it to him. Though frail, he survived the labor camp, leading its choir.

After traveling the steppes and countryside to preserve Jewish tradition, Beregovsky realized the power music had in the face of the unspeakable.

“The more we learned about the horrors and inhumane living conditions of Jews in the camps and ghettos, the more difficult it was to imagine even the slightest possibility that song could exist here,” Beregovsky wrote. But, he added, the expeditions confirmed that music was in fact essential. “It was a means of survival, a means of salvation. As in any dire situation, a person feels when he creates, even in the most inhumane conditions.”

With Kyiv now in the crosshairs of Russia, the fate of Beregovsky’s cylinders, housed in the National Library of Ukraine, is once again precarious.

“These cylinders survived through Stalin and Hitler,” Yakovich said. “I suppose everything is OK with them. They’re still in the library. I hope so.”