How the Manischewitz gets made — a behind-the-scenes taste of America’s most iconic kosher wine

For the syrupy Concord grape wine to be kosher, it all has to be made over the course of one, single week, known as ‘Kosher Crush’

Manischewitz wine is a classic for Jewish holidays of all varieties. Photo by Benyamin Cohen

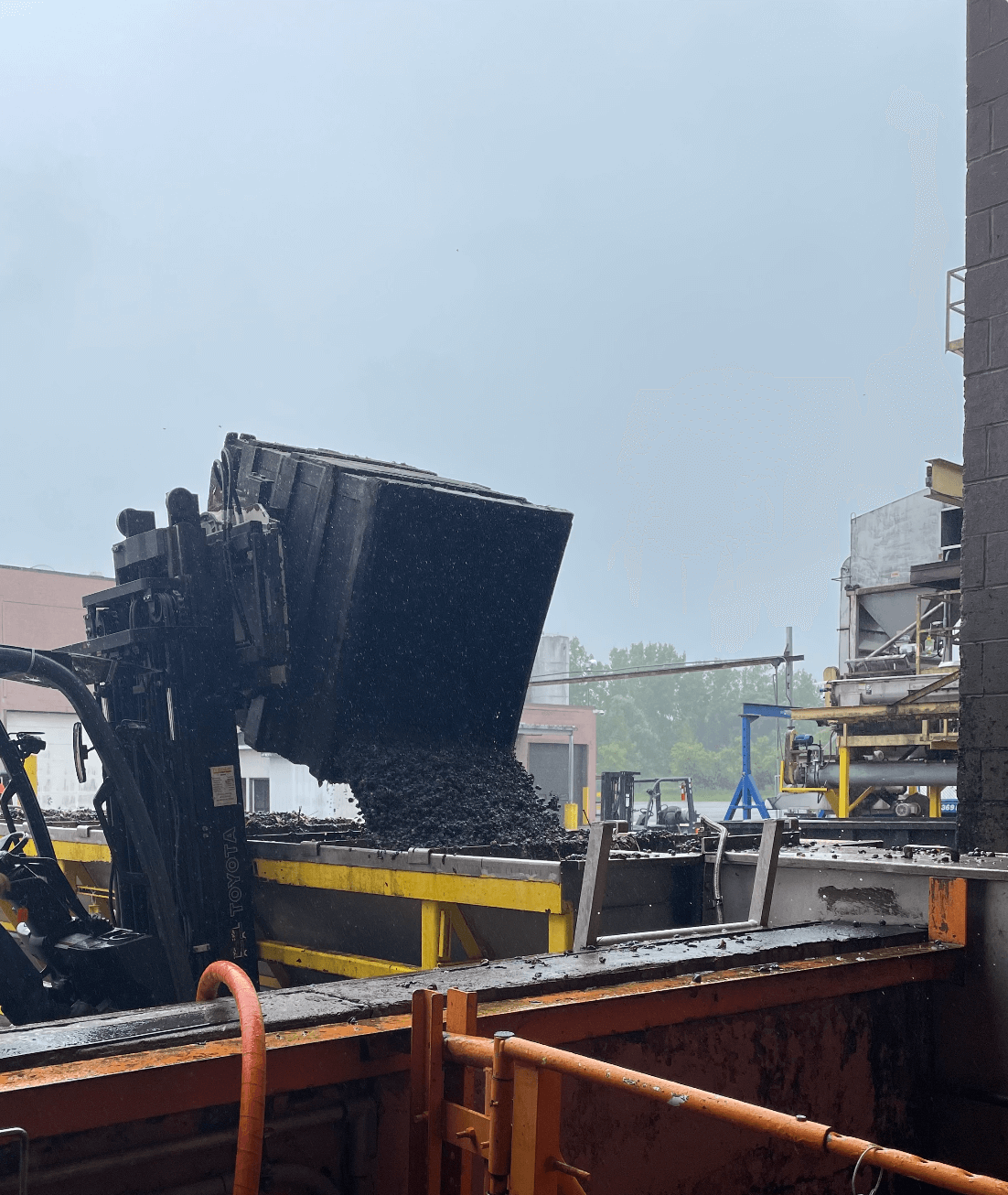

Every drop of Manischewitz wine for the year is made during one, single week, known to workers at the winery as “Kosher Crush.” The moniker has multiple meanings: It refers to the act of literally crushing the entire year’s harvest of Concord grapes, and to the logistical crush of managing to pull off such a feat in a week.

This isn’t entirely unheard of in the wine world. Grapes are harvested at peak ripeness, often over just a few days, and then they need to be crushed and begin fermenting to retain that specific flavor. So there’s always an element of time pressure.

But for Manischewitz, there’s an added logistical hurdle: The wine has to be kosher. And because the winery where Manischewitz is made, in the upstate New York town of Canandaigua, also makes many other brands of non-kosher wine, all of the winery’s equipment has to be made kosher before the crushing begins — and none of the other brands can use it until Manischewitz has crushed every last Concord grape.

You might be imagining oak barrels and barefoot winemakers stomping grapes, but, as Manischewitz’s senior winemaker Joyce Magin told me over the phone, this is “not a small boutique winery.” E&J Gallo, which also makes some favorites you may remember from college, such as Barefoot wine and those gallon jugs of Carlo Rossi sangria, recently acquired Manischewitz from Constellation Brands, another large beverage company.

(Manischewitz food products — matzo, Tam Tams, gefilte fish and so on — are owned by a different company and are entirely separate from the wine. While they share the brand licensing, they have nothing to do with one another.)

The high volume and corporate ownership means Manischewitz’s equipment is large and automated, and the goal is consistency. It’s a different world from small wineries that experiment with different aging processes or grapes, or keep a bottle on the shelf just to see how it tastes in 20 years. There’s no savoring the specific flavor of the 1998 vintage and there’s no terroir. All Manischewitz tastes like Manischewitz — sweet and redolent of its signature Concord grape.

But grapes are finicky, harvests are all different and fermentation is hard to control. So how do they do it? Kosher Crush is just the beginning.

Complicated kashrut

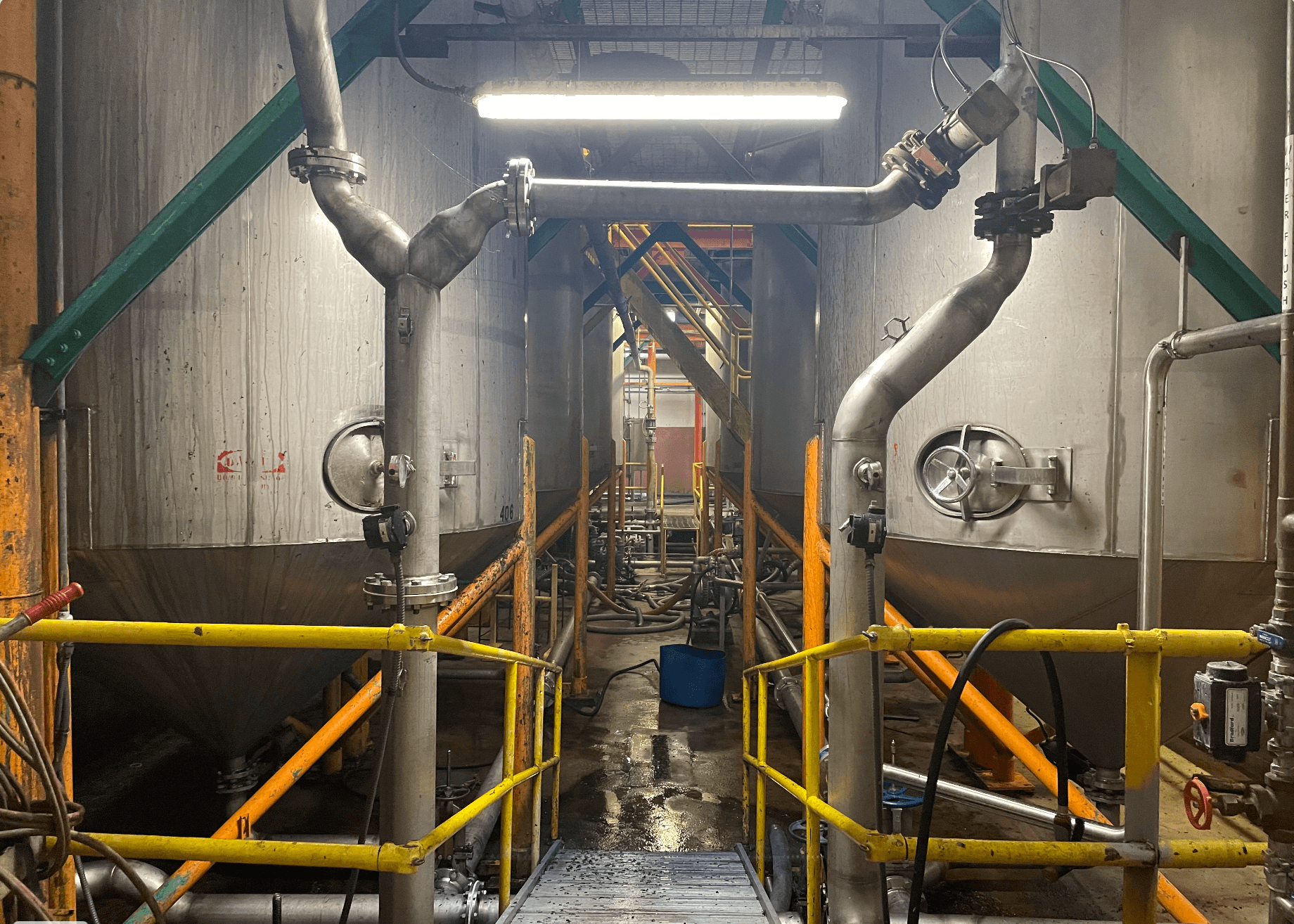

Kashering requires shooting hot water and steam through the equipment until it reaches a high temperature. This is no small feat, given that Manischewitz’s tanks hold up to 300,000 gallons of wine.

But it’s not just that: In order for wine to be considered kosher, the Orthodox Union, which supplies Manischewitz’s certification, has determined that rabbis have to control the entire process.

According to Jewish law, a non-Jew handling wine could use it for idolatrous purposes, thus rendering it non-kosher. That means if Uncle Patrick, who never converted when he married in, pours wine for someone, it might not be kosher enough for your Orthodox family members to drink.

There is, thankfully, a loophole that can save a lot of family drama: boiling the wine. Once the wine is heated, or made “mevushal,” it stays kosher even if mishandled. (It can still lose its kosher status if someone adds a non-kosher ingredient though.) Until the wine has gone through the mevushal process, however, the winery has to remain in the hands of the OU.

“They kosher the equipment and then they operate all of the equipment that we use to crush the grapes,” explained Magin. “The decanters, the destemmers, the presses, all of that. They are in complete control of the equipment.”

“From turning on the forklifts even,” added Claudia Gerecke, the associate winemaker for the brand, who was also on the call.

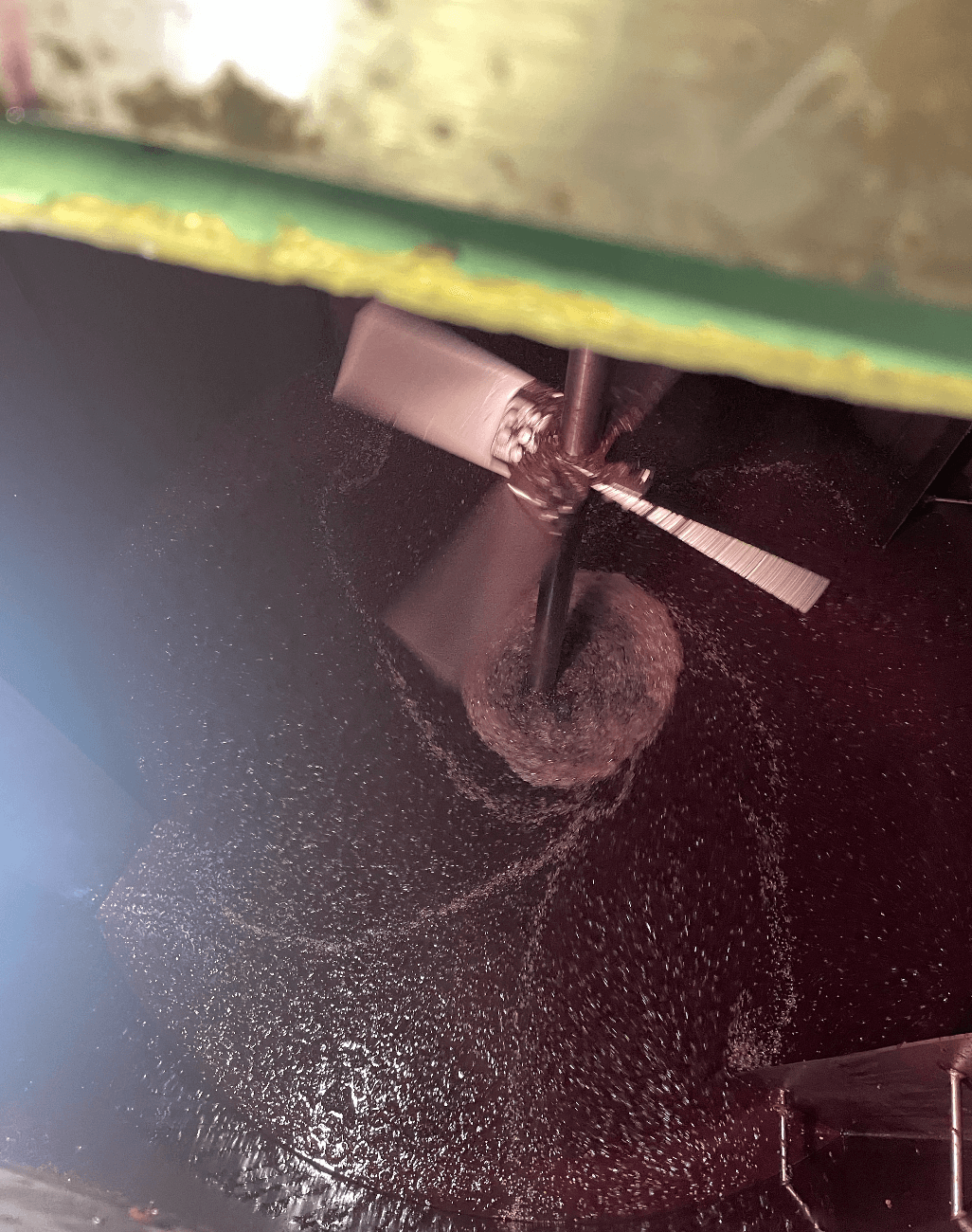

Once everything is kosher, the crushing begins. The main goal is to separate the juice from the pulp, so the grapes have their stems and seeds removed, and then the remaining solids are pressed to extract the remaining juice. It’s then run through a centrifuge to extract even smaller solids, and then run through the mevushal process to heat the wine for kosher standards.

After the equipment is kosher, the heating is the only thing that differentiates Manischewitz’s process from other winemaking. Even though it is basically a pasteurization process, which is commonly used in processing many other foods and drinks, oenophiles believe the heat destroys the subtle flavors of the grapes. (They probably feel the same way about Manischewitz’s added sugar, though, so perhaps it’s a moot point.)

Finally, it’s cooled so the yeast can be added and put into giant tanks to ferment. Those have to be kosher too, as do all the tubes and pipes involved, and everyone working with the tanks needs to know the rules of kashrut.

That sweet, sweet Manischewitz taste

The real work of making Manischewitz’s juicebox-adjacent flavor comes after the juice enters the fermentation tanks.

I spoke to winemakers Magin and Gerecke on the Friday before Rosh Hashanah, which was also the final day of Kosher Crush; things sounded hectic. The two women — who both fondly refer to the wine as “Mani” — are in charge of keeping Manischewitz’s famously sweet taste on-brand.

I was surprised to learn that the grapes are “fermented dry,” meaning the yeast eats all of the sugar in the juice and the wine is not initially sweet. It’s after the fermentation that Magin and Gerecke begin to titrate the flavor, adding sugar until it gets to the trademark syrupy taste.

But this is not done by the classic sip-and-spit you may have seen on a Napa Valley wine tasting tour. Both women have backgrounds in biology and chemistry that are essential to analyzing and adjusting the wine.

Magin studied biology and chemistry, and began working in the winery’s lab 30 years ago before she eventually became a winemaker. Gerecke studied ecology and environmental biology at Cornell. Before graduating in 2016, she took a viticulture class for fun that led to an internship at Gallo’s California winery.

Both came to winemaking through science; neither mentioned a deep love for wine they might have had before they entered the commercial industry, though of course both have developed a palate for it. Instead, they talked about the creative problem-solving involved in the chemistry of keeping a wine’s taste consistent.

“We’re going to be blending it up to meet the specs, we’re going to be using sugar to sweeten it just to the right level,” said Magin. “We want the wine to be consistent with the same bottle of Manischewitz Concord that Sam had when he was 13 years old.”

It’s not just Jews who love ‘Mani’

Oenophiles might try to taste each bottle for funky flavors such as ammonia or manure, or savor the distinct taste of each year’s harvest. But Manischewitz isn’t shooting for the wine snob market. Instead, it’s aiming for those nostalgic for childhood Seders — and for new drinkers. So it’s careful not to put people off.

For example, naturally occurring sediments are common in wine, and widely accepted in Europe. “But the American consumer doesn’t like that,” explained Magin, so Manischewitz performs a difficult process to make sure no precipitates end up at the bottom of the bottle.

Manischewitz is iconic as a kosher wine; it’s been making red wine, sweetened for palatability, since the 1940s. But while both winemakers were careful to acknowledge its rich Jewish tradition, there’s also a more basic element of its appeal: its price point.

Manischewitz, like many of Gallo’s other wines, is part of what Gerecke called the “popular category” of wine, which is to say that it’s under $15 per bottle; I saw it retailing for $8 at a NYC wine store. (Many of Gallo’s wines seem to fall into this category.) And it has found wide appeal in non-Jewish markets for over 50 years.

While Gerecke didn’t quite come out and say she knows the wine is famously made fun of for its taste, the winemaker was frank about the fact that the brand knows its sweetness doesn’t appeal to wine snobs — but that’s not who it’s courting.

“A lot of the time when we’re looking at bringing new friends to the wine market, whether kosher or not kosher, we’re looking at making the product as accessible as possible,” said Gerecke. “When people are getting introduced to wine, they’re not starting with the $100 tannic, astringent, Napa Cab. They’re just not.”

But that’s not to say that the winemakers themselves share the tastes of their consumers. Magin said she prefers “deep, dark red wines.”

“I could sit at a party and just sniff a glass of good red wine all night long,” she said. “I could do nothing but sniff it because of the nuances that come in a glass of wine.”

Gerecke, for her part, likes a dry wine. But, she pointed out, the best part of drinking wine is contextual — doing it with people you love. “It’s something that’s designed to bring people together, whether it’s over the Rosh Hashanah dinner table or an afternoon in summer,” she said. “But during harvest, when all you’re doing is tasting wine, beer and gin are my go-tos.”