Behind the swankiest new hotel on the Lower East Side, a swanky Jewish history

Visitors to Nine Orchard might not realize they’re living out a Jewish immigrant’s American dream

The former home of the Jarmulowsky Bank, now a swanky hotel, Orchard Nine. Photo by Andrew Silverstein

It’s become cliche to comment on the irony of how the hardscrabble Jewish Lower East Side has become a fashionable district. But it’s hard not to say anything about that as I sip a $22 negroni served by a white jacket bow tie-wearing waiter at the Swan Room, the bar at the neighborhood’s newest high-end hotel, Nine Orchard. After all, the hotel is just blocks away from the cramped quarters where my family once hunched over sewing machines by day and laid their heads at night.

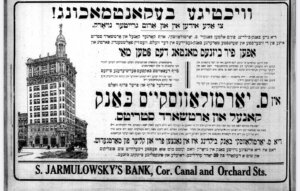

If there is one place in the old Jewish Lower East Side that seems destined to a life of luxury, it’s here. Nine Orchard, which opened in June, is a new incarnation of the old Jarmulowsky Bank building, a 12-story 1912 Beaux Art tower designed by the firm Rouse & Goldstone. When Jewish immigrant Sender Jarmulowsky announced the construction of his building in a 1911 trade magazine, he promised it would be the East Side’s “first strictly high-class tall bank and office building.”

The building at the corner of Orchard and Canal has caught up with the neighborhood’s other Beaux Art tower: the Jewish Daily Forward building, this publication’s former headquarters, built the same year. An engraved bust of Karl Marx above the door illustrated the newspaper’s politics at the time of construction.

The two towers came to dominate the local skyline, floating their opposing ideologies over the modest tenements. “You have this capitalist bank doing a dance with the socialist Forward building just a few blocks away,” said architectural historian Andrew Dolkart. “It’s one of the most spectacular juxtapositions of a building that you can see in New York.”

In 2006, the Forward Building, called “the people’s temple,” became luxury condos, while the Jarmulowsky Bank building, known as the “temple of capitalism,” was still half abandoned and covered in graffiti. The banking hall then housed Happy Shabu Shabu, a Japanese hot pot restaurant with a $5.99 lunch special.

In 2011, DLJ Real Estate Capital Partners purchased the bank building and the adjacent property for $41 million. For years, rumors swirled about a condo conversion and an Ace Hotel. A decade and an extensive renovation later, Nine Orchard finally opened.

In the interim, this part of the Lower East Side abutting Chinatown gentrified, with boutiques, bars, cafes and galleries popping up on almost every corner. The transformed area in front of Jarmulowsky Bank building has been dubbed “Dimes Square,” a reference to the trendy local restaurant Dimes. Twitter exploded earlier this year, when New York media types, somewhat ironically, claimed that this micro-neighborhood, with its mix of millennial skaters and literary cocktail sippers, defined COVID-era downtown New York cool.

The more polished and mature 116-room hotel is a late arrival to the scene. Rooms go for over $600 a night. The Swan Room occupies the original two-story bank hall; the teller booths have been replaced by plush velvety couches. After decades of neglect, the hall has been restored to its original grandeur. The high vaulted ceilings, columns, stone carvings, large windows and classic clock beg comparison to Grand Central Terminal, which opened a year after the bank building.

For the renovation, DLJ went with an obvious choice, Ron Castellano, the architect who redesigned the Forward Building. Studio Castellano’s finest work is found on the roof, where they installed a 60-foot tempietto, a domed structure based on photos of the building’s original temple-like roof structure that was removed in 1991. The work inside and out is impeccable and goes well beyond the landmark preservation requirements.

Nine Orchard may have restored the building’s glory, but one thing it doesn’t convey is its Jewishness. The New York Times has noted that Jarmulowsky was a “Polish immigrant,” but articles in the Times, The New Yorker, Conde Nast Traveler and Vogue all fail to mention the hotel’s Jewish connection.

After visiting the hotel, I’m not surprised. The Forward building still displays large Hebrew letters spelling out “Forverts” in Yiddish. The nearby apartment building on the site of the old Streits Matzo factory pays homage to the kosher bakers in its lobby art. But, aside from the engraved Jarmulowsky name, the bank building never had an outwardly Jewish identity, and though the commissioned art and exquisite decorations in the hotel might feel both modern and classy, they don’t hint at a Jewish past.

DLJ partner Andrew Rifkin, who is Jewish and whose family came through the area, could have also taken a cue from the Hoxton Hotel in Williamsburg, which recently opened a modern Jewish restaurant called Laser Wolf by Israeli chef Michael Solomonov. Rifkin instead went with the Uruguayan chef Ignacio Mattos to head the Swan Room, the bistro Corner Bar, and a soon to open fine dining restaurant. Mattos, known for his Michelin-starred modern American restaurant Estela, didn’t find inspiration in the old Lower East Side. There is no babka on his dessert menu and none of his 22 bespoke cocktails have a Jewish twist.

Dolkart suggested that a plaque be added to the building’s facade to share its story, but the European travelers and the neighborhood tipplers do not seem interested in Jarmulowsky history. Rifkin commissioned Jeffrey Rotter to edit a book on the building’s and the Jarmulowsky’s family history. The book, “At the Corner of Canal and Orchard,” sits in every room, but from what I gather from conversations and the media, it goes unopened.

The city’s tastemakers, however, are missing out on a great story. The Swan Room was where Jewish garment workers once deposited their hard-earned savings and purchased ship tickets to bring relatives to the U.S. The cheapest steerage tickets cost the price of today’s shrimp cocktail ($35).

Although Jarmulowsky was a Jewish immigrant, he wasn’t the Forverts-reading tenement-dweller type. Sender was born in Grajewo, Russia (now Poland), in 1841 and came to New York in 1873. By the turn of the century, he’d become known as the “East Side J.P. Morgan,” a millionaire banker and respected member of the growing Eastern European Jewish community. He was a founder of the synagogue on Eldridge Street and advocated for Jewish businesses to have the right to close for Shabbat.

The bank building didn’t escape the harsh realities of the Lower East Side. Three weeks after it opened, Jarmulowsky died. His sons took over, but with disastrous results.

“In 1917, immigrants eager to send money back to relatives in war-torn Europe found that their money was not available,” according to a Museum at Eldridge Street installation. Wartime depositors rioted outside East Side banks and the Orchard Street financial institution closed. Two Jarmulowsky sons were arrested for fraudulent activities and overnight the family name became associated with financial ruin.

After the bankruptcy, the building became just another eastside loft. According to the 2009 Landmark Preservation Commission report, in the 1920s, it was “teeming with manufacturers of garments and various types of finishers.” Then, from the 1940s to 1960s, it was occupied by a piano manufacturer before east Asian sewing factories came to dominate most floors.

By the 1990s, artist loft parties and illegal makeshift apartments existed side-by-side with the building’s “Chinese sweatshops” and “brothels” according to a 2013 article on the website Bedford + Bowery.

Other businesses play up this gritty and freer era. The restaurants and boutiques of Dimes Square restaurants and shops keep the Chinese-language signage of previous tenants as a mark of authenticity. Nearby, on the Bowery, the streetwear brand Supreme took over the landmark 1899 Germania Bank Building. They opted to keep the graffiti, using the urban decay aesthetic to push $168 hoodies.

Nine Orchard erased both the graffiti and working class history. They created the pristine aesthetic and experience expected of a fashionable high-end hotel.

Still, one doesn’t need a historian or an interior decorator to realize the area’s connection to struggling immigrants. It’s in plain sight. According to NYU’s Furman Center, the Chinatown and Lower East Side area has a poverty rate of 24 percent.

On a recent Saturday morning, vacationers started their day at the hotel’s restaurant with bellinis and perfect sunny-side-up eggs. Outside, the line for a food pantry run by the Buddhist organization Tzu Chi wrapped around the corner. Elderly East Asian men and women stood patiently waiting to fill their fabric bag carts with fruits and vegetables.