Back from the dead — the resuscitation of an artwork that wasn’t supposed to last

Like its brilliant creator, Eva Hesse’s ‘Expanded Expansion’ conveys the ephemerality of existence

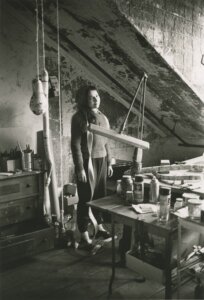

Eva Hesse in front of ‘Expanded Expansion,’ 1969. Courtesy of Courtesy Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Eva Hesse’s monumental work of art “Expanded Expansion” was kept in storage at the Guggenheim Museum for nearly 35 years. In the 1990s, the work was deemed unexhibitable. In 2000, the work was evaluated to see if it could be included in a retrospective, but there were tears in the fabric and concerns about the work’s structural integrity.

After considerable work by conservators conducted over the course of over two years, “Expanded Expansion” is now being exhibited again. The Guggenheim’s curators have used the word “resuscitated” to characterize the return of the artwork, which, due to the deterioration of some of its elements, is somewhat darker and more brittle than when it was last seen.

Hesse redefined modern sculpture through the use of new materials like resin, latex rubber and fiberglass. Ironically, these materials proved to be ephemeral, raising questions about the nature and definition of art and whether art needs to last forever. As with some of the smaller studio works on display in the exhibition, the decay of the materials in “Expanded Expansion” mirrors the passage of time on a human body; the fabrics have yellowed with time, just as skin does with age.

Hesse’s choice of materials reflects the tragic temporality of her short life. Hesse died at the age of 34 from a brain tumor and her early death lends a heightened poignancy to everything in the exhibit. She looks so young and vibrant in the silent, 1968 color video “Eva Hesse in her Studio on the Bowery,” filmed by Dorothy Levitt Beskind. “Expanded Expansion” itself was a standout work in the Whitney Museum’s 1969 major exhibition “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials,” which featured the work of 20 “post-minimalist” young artists including Richard Serra and Bruce Nauman. In that same year, when Hesse was showing a new assuredness and daring in her work, her brain tumor was discovered. She died one year later.

As she said herself in a January 1970 interview with Cindy Nemser, a few months before her death, her entire life was one of “extremes.”

“I was told by the doctor that I have the most incredible life he ever heard,” Hesse said. “Have you got tissues? It’s not a little thing to have a brain tumor at 33. Well, my whole life has been like that.”

Hesse goes on to explain that she was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1936. Following a children’s pogrom in 1938, she and her older sister were put on a train to Amsterdam. They weren’t picked up as expected by her aunt and uncle so she and her sister were sent to a Catholic children’s home. Her aunt and uncle ended up in concentration camps but her parents were able to pick up her and her sister, and get from England to America in the summer of 1939. In New York, her mother was institutionalized and her father was studying to be an insurance broker, so Eva was often left at home alone at night and in and out of different homes, causing her a great deal of anxiety. When Eva was 10, her mother killed herself.

“My life has been so traumatic, so absurd — there hasn’t been one normal, happy thing,” she said. “Art and work and art and life are very connected and my whole life has been absurd. There isn’t a thing in my life that has happened that hasn’t been extreme — personal health, family, economic situations. .And now back to extreme sickness — all extreme, all absurd.

“Absurdity is the key word,” she added. “It has to do with contradictions and oppositions.”

“Expanded Expansion” becomes the embodiment of absurdity through the juxtaposition of extreme opposites. Hesse designed it so its width is flexible: It could be set up to be narrow or to be spread wide apart. The scale of the work is huge and imposing, larger than life, and yet the materials are fragile and vulnerable, resembling skin and flesh. The materials are opposites as well — soft rubberized cheesecloth and hard reinforced fiberglass. When one stands close to “Expanded Expansion,” it looks like curtains of skin, wrinkled and sagging.

In her interview with Nemser, Hesse explains another inherent contradiction about “Expanded Expansion” — the juxtaposition of ridiculousness and meticulous concern that gives it an absurd quality: “[I]t has that feeling — I can’t use that word any more — absurdity. Because it potentially has quite a few associations and yet it is not anything. So maybe that increases its silliness. And then it is made fairly well so it contradicts its ridiculous quality because it has a definite concern about its presentation. You think, ‘Well really — it can’t just be a whim, you know, it’s too considered.’ There’s a great deal of concern and it’s visible.” Standing before “Expanded Expansion,” one gazes in awe at its careful construction and grand scale and at the same time one can sense the humor, the absurdity of it.

A centerpiece of the exhibition is “The Afterlife of Eva Hesse’s ‘Expanded Expansion’” — a 15-minute Guggenheim-produced documentary about conservationists’ efforts to preserve “Expanded Expansion.” I found the film terribly touching. The care this team has lavished on this work made me think of a chevra kadisha tending to a body.

Hesse was aware of the fragility of her work.

“Part of me feels that it’s superfluous and if I need to use rubber that is more important. Life doesn’t last; art doesn’t last,” she said.

But, she added, her experience of being ill put the idea of making art that could last “into another perspective.”

She added: “I’m not sure how I feel about it, if it matters — it probably shouldn’t — but I’d like to try the rubber that will last.”

She realized that like life itself, her feelings were absurd, that it shouldn’t really matter to her if her art lasted, but, in the end, she admitted, it did. She didn’t get to try the type of rubber that would last, but the holy work of these conservationists, and the entire Guggenheim’s exhibition, has made sure that her art will endure for future generations.

“Eva Hesse: Expanded Expansion” is on display at the Guggenheim until Oct. 16.