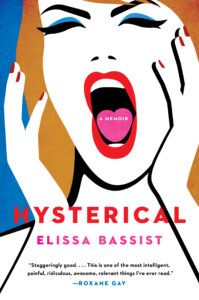

How simply living as a woman can feel like a preexisting condition

Elissa Bassist’s illness memoir is enraging, hysterically funny and very, very Jewish

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

“I had what millions of American women had,” Elissa Bassist writes in the first pages of her illness memoir “Hysterical.” “Pain that didn’t make sense to doctors, a body that didn’t make sense to science, a psyche that didn’t make sense to mankind in general.”

Like many great memoirs, “Hysterical” is less autobiography than argument — in this case the argument that modern society is making women sick. Sick from being assaulted by violent sexual imagery every day, sick from being expected to be nice and eager at work, sick from being told to quash our anger, and finally sick from all the ways in which ‘no’ still doesn’t mean ‘no.’ Instead it means, well, maybe not, unless you prefer otherwise. Or I’m so sorry for denying you pleasure, will you ever forgive me and how can I make it up to you. Or I must be a raging bitch, because only a raging bitch would ever deny you what you want.

This last meaning occupies a good part of the narrative, which toggles between very funny (Bassist is a humorist and editor of the Rumpus column “Funny Women”) and enraging, as she begins to examine all the ways in which she’s buried the certainty of her own boundaries behind a compulsive desire to please. There’s the “bad sex” with her college boyfriend which will take her years to recognize as something much darker, the exploitative (male) bosses with impeccable national reputations, and then finally the toll of working for years in a media landscape in which young female writers are encouraged to bare their souls, and their trauma, for the sake of what editors call “engagement” and what the rest of us call “having random strangers on Twitter threaten to rape you to death.”

The book is also a medical mystery of sorts, as Bassist goes from doctor to doctor in search of help for debilitating pain that at different points includes but is not limited to raw sore throats, crippling headaches and blurred vision. On the way she’s gaslit, ignored, overcharged, dismissed, and — finally — given both a surprising set of diagnoses and a treatment plan that launches her into recovery.

I spoke with Bassist over Zoom about the smokescreen of the mind-versus-body question, the need to rethink self-defense, and of course, what being Jewish might or might not have to do with it all. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start with the title. How did you choose it?

I asked myself, “If I were to describe my book in one word, what would it be?” And immediately I thought “hysterical” because every meaning of the word fit: I was writing about uncontrolled extreme emotion. I was writing about a medical mystery and about how people use the word to dismiss whatever women say, think and feel. And also “hysterical” because I’m. So. Funny.

The idea that emotional stress manifests in physical pain is often weaponized. “Oh, it’s psychosomatic.” “Oh, it’s all in your mind.” So how do we take that connection seriously without dismissing women’s health complaints?

One of my chapters is titled “Hysteria Reboot” because I think something can be true and also be used against us — and anything will be used against us whether it’s true or not. For example, there’s hard evidence that stress can hijack health. But at the same time, many people will say that our emotions are making us sick, so we should stop being so emotional. And rather than validate “hysteria,” I hoped to confirm the mind-body connection.

To give us permission to acknowledge that each influences the other?

This question of mind vs. body, it distracts from the overall problem, which is that we don’t listen to women, and we don’t believe women. I wish doctors would say things like, “Let’s share in the decision-making. Let’s talk about what we can do to help you. I want to help you. Please let me know what makes you feel uncomfortable or afraid.”

If only.

I wish it were more of a conversation, as opposed to one man talking and me shutting up and staying neutral to be “a good patient.” I forget, so often, that it’s the doctor’s job to answer my questions.

You argue that what is making us sick is everything: what we see in the media, how we’re expected to respond to male desire, and how we approach work.

The workforce I entered as an elder millennial was one in which it was understood that you say yes. Yes to overtime, yes to working for free, yes to everything if you want to succeed. The first man I worked for said in an interview that “no” was for “wimps and pussies.” If women said no, then they were rude and difficult. If women had boundaries, then they were bitchy. If women stood up for themselves, then they were unlikable and terrible to be around. I don’t know why I’m using the past tense.

So now we hit the question of whether life and work and relationships are different for Jewish women. Think of Susie and Cheryl on “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” Cheryl is blonde, perfect and polite. While Susie — well, the actor who plays her is a beautiful woman in real life, and they had to put her in vulgar, unflattering clothes and makeup, because she is playing a character who can’t be attractive by definition. She’s loud, she’s bitchy, she’s emasculating. But she’s also a fabulous boundary setter. To me, kind of a hero. Do you think that, for better or for worse, even the worst stereotypes of Jewish women help exempt us from these kinds of nice girl expectations?

Not for me. I grew up in Colorado and was so afraid of Jewish stereotypes that Susie embodies. I straightened my naturally curly hair. I tried not to be bossy or act like a princess. Even though that didn’t matter — I would get called a princess no matter what I did or didn’t do. I remember feeling afraid to even say, “I’m Jewish,” afraid to say that I celebrated Hanukkah because it wasn’t “cool.” Christmas was cool. So I silenced those few words and details. I had this inherited fear of disclosing.

Did your family talk about the Holocaust?

Yes, as Jewish families love to do.

What is your family medical history?

As I write in the book, my grandmother’s experience with doctors was both abhorrent and a secret. My grandmother and I had a lot in common — we were embarrassed by our pain and our suffering, by our mental and physical anguish, and in our family there was so much unsaid about it.

I think my own voicelessness, which was part of my sickness, was due, in part, to the trauma I inherited: If in your own bloodline there’s the idea that you’re disposable, and that people want to see you dead, it becomes easy to believe, consciously or not, that you shouldn’t be alive and you shouldn’t do whatever it takes to stay alive. Carrying that in your body is a part of what it means to be Jewish, to me. And then as American woman, this warped notion is reinforced in entertainment that bombards us with images of raped women and dead girls.

This urge to be a good patient, a good date, a good worker — it becomes a survival skill. But one that might actually be hurting us. There’s a striking scene in which you talk about taking a self-defense class, but when the question is, “What if a guy wants to fool around but you don’t, yet you don’t know how to say so?” the instructor is completely flummoxed.

Can’t men just learn to listen and to take no for an answer? And not feel entitled to sex? No, instead, we must learn how to wield mace and do a roundhouse kick to the nuts. But what I had to learn was self-defense in terms of communication, like learning how to say no and set boundaries, because it isn’t as simple as “taking no for an answer” since women like me haven’t been taught to say no. Sure, you can say no, and still fall victim to sexual violence, but in this scene I’m writing about women who don’t know how to say no, and are therefore complicit in sexual violence against themselves. That’s what happened to me.

You were complicit?

Oh, I think I was very complicit. I write in the book, “If my boyfriend said he loved me while hurting me, then I would consent to be hurt.” I said “yes” when I was thinking “no.”

Learning to say “no” was important in so many different parts of my life. “No” to working for free. “No” to that second drink I don’t want. “No” to pain. I had to learn the most basic of “no”s, to say no to being available for what other people wanted me to do when it makes me discount what I want.

What advice would you give to women still struggling with this — which is to say, almost all of us?

Elizabeth Olsen said that her sisters’ best advice was that “no” is a complete sentence. First we need to learn that “no” is not a bad word; it’s not rude or combative or bossy. It needs zero explanation or defense or apology. We must redefine “no” in our own minds — and then practice it with abandon.