Still pining for John McCain, a ‘Big Guy’ seeks to take back his country

In A.M. Homes’ novel ‘The Unfolding,’ the Jewish author imagines a life antithetical to her own

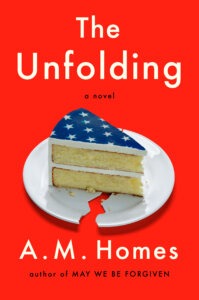

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

I have been reading A.M. Homes’ work since I was in college. “The Safety of Objects,” her mind-bending and boundary-crossing debut story collection, had one of the most profound effects on me as a reader who would be a writer. You can write about whatever you want, the book showed me, you just find your own voice and do it well.

Since that collection, Homes has published nine works of fiction and a memoir, “The Mistress’s Daughter,” which chronicles her experience meeting her immature and lonely birth mother and her birth father, who denies her existence. It examines her family history and her place within it. She leans into discomfort, both for the reader and the writer. So many of Homes’ indelible scenes are imprinted on my imagination: a suburban couple doing drugs while their kids are at Grandma’s, a couple coupling on the kitchen floor while live lobsters escape the stew pot, a man with his fist in a turkey. These moments are like John Currin paintings where precision and skill and humor punctures social mores.

A decade ago, Homes and I talked about her previous novel, the Women’s Prize for Fiction winner “May We Be Forgiven.” That novel, both satirical and intimate, examined such topics as warring brothers, Jewish faith and Richard Nixon.

Much has changed for all of us in the past decade, so I spoke with Homes via Zoom about her new novel, “The Unfolding.” Books in several languages appeared on the built-in shelves of her home in New York City. There was a rolling suitcase on the floor — she just returned from a book tour and has turned her attention to the new semester at Princeton where she teaches creative writing.

“The Unfolding” looks at the 2008 presidential election through the perspective of a rich white Republican man who, smarting from McCain’s loss to Obama, will do anything to end progressivism in the White House. The story opens on that historic election night in Phoenix, Arizona, where our protagonist, “The Big Guy,” who has helped finance the campaign, decides to form a group called the Forever Men, who will stop at nothing to “take back” the country.

Even though little takes place in D.C. proper, this is a deeply Washingtonian novel — Homes grew up in Chevy Chase, where roads were blocked off for President Ford’s motorcade and where Watergate was a real place you had to drive by to get to the airport.

I grew up there, too — in fact, Homes and I, at different times, went to the same high school (go Barons!). And, in an odd coincidence, since we both grew up in Jewish families, we went to the same Christian sleepaway camp in North Carolina. Homes and I laughed about how we had to pray and how on Sundays we had to wear polyester middies that didn’t fit, and how much we loved archery and the rifle range. But picturing her there, singing hymns in the dining hall over grits and gravy, made me think of something more serious, which is the outsider’s vantage point. For a writer, that position can be solemn or humorous, but it is essential.

While “The Unfolding” examines what is to come in the post-Obama era, including the Jan. 6 attack, it seems to anticipate rather than chronicle the real life events we know well, as they grow organically out of these characters’ decisions. Formally the book does something important as well, which is to merge two distinct styles of fiction. It stitches together a broad social novel (generally seen to be the purview of American men, dealing with in the political and social implication of men’s lives) and a more intimate domestic novel that details, quite movingly, the lives of a man’s daughter and his wife.

Big Guy’s wife, Charlotte, was born in a time when a woman’s most important life choices were relegated to which husband she would pick. In “The Unfolding,” she, and her daughter, Meghan, a student at an elite prep school outside of Washington D.C., both journey to different self-discoveries.

“I wanted to look at the evolution of women’s lives, and I wanted there to be this multigenerational view,” Homes told me. “We think women have come so far, and they’re each having their own kind of awakening and coming to their own consciousness about their lives. The different generations reveal the different awakenings.”

This more intimate look at the lives of women in a domestic sphere has been often relegated to the category of “woman’s novel.” Homes recounted one of her recent bookstore readings, where a man picked up her book and said he would get it for his wife. When she protested, saying, “look, it’s about men, you can read it,” he still demurred, placing the book back down on the table.

Meg Wolitzer called out the idea that women can’t or don’t write big books of ideas in The New York Times over a decade ago, but it persists.

“Men get a lot of extra credit when they write a family novel. Like when Jonathan Franzen writes a family novel, they’re like, ‘oh, a brilliant family novel.’ Meanwhile, women write family novels all the time, and nobody seems to notice. I often work with what is the least likely character. So, in a way, who is the least likely character to talk about our system? And you could say it’s a bloated big guy, a guy who is completely oblivious to his own privilege, his own power. And importantly, he’s oblivious to the space he occupies.”

One of the many secrets to writing the long sustained project of a novel is that once you get to know your characters, whomever they may be, you put them to bed when you get up from your desk and wake them up when you sit back down. You are with them for years this way, and it got me thinking about having to face a character like Big Guy every day in the world of one’s own fiction.

“This guy is certainly antithetical to how I grew up. Certainly antithetical to the values in my family, the people I saw around me,” Homes said. “And yet I think about each character in a deeply human way. Some people say to me, ‘Am I supposed to like this person?’ But I think liking them is sort of irrelevant. I think I was able to write him because he was able to reveal his own vulnerability and insecurity to me. As much as his values and beliefs are quite different from mine, I feel quite tender towards him. I really like spending time with people who live in very, very different ways and who think very differently because it’s kind of fascinating for me to go to his house.”

What would be in the Big Guy’s house? Homes theorized that Gentiles and Jews use different kinds of toothpaste. “Crest with the blue and white,” she said, “is Jewish toothpaste and Colgate is for the gentiles.”

Homes’s previous novel, “May We Be Forgiven,” was very centered on a certain Jewish experience, and Homes herself is Jewish.

But in her latest, “my identity is largely absent — which is both interesting and a problem,” she told me. “I don’t feel like I see myself represented in the world around me — I don’t feel like I can easily describe my identity. As an adopted person I would say the experience is akin to being born as Barbara Bush and growing up being told you are Emma Goldman. My absence of a firm identity also allows me quite easily to inhabit the experience of others, and so that part is fun and liberating.”

Homes knows that the ability to shapeshift gives her a choice not everyone has. “Of course,” she tells her students, “if the glass door was locked, and I was knocking on it, banging to get in, a person on the other side would see me and they would let me in. I would not be locked out.”

I can think of few people who have observed American life through fiction in such a wide and varied and exacting way. I think of A.M. Homes prying back the bow for archery at our sleepaway camp in North Carolina. She told me the counselors cried when Nixon was indicted. I still remember singing about Jesus. Our middies were so scratchy. They didn’t fit. Perhaps, Homes told me, her next project will be a new memoir, one that takes another look at her upbringing as an adopted child.

Or, she said, almost as an aside, she has written a piece that shows Big Guy’s daughter all grown up. I think of what will become of the generation whose parents contributed to the rise of the new Republican party. Who are the daughters of the people who voted for Trump, twice? Who will they be and how will they navigate the swiftly shifting political and social world? I want only A.M. Homes to show me.