An ancient community of 850 on biblical soil — with Jewish roots

In a new documentary, Samaritans look to their heritage from the 12 tribes of Israel while also facing the threat of extinction

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

No. Not that one lonely Samaritan, on a road two millennia ago. This is not about him, famous from the New Testament parable of The Good Samaritan who stops and helps a beaten traveler after two previous passersby have ignored him. The feature documentary “The Samaritans: A Biblical People” is not about that one ancient Samaritan, but rather, about the community of contemporary ones and their heritage.

Actual living, breathing Samaritans, it seems, are defined by what they are not. Neither Muslim nor Christian, nor quite even Jewish by modern terms, the Samaritans are a tiny minority trying to preserve millennia of traditions that are almost unknown to the outside world. It is easy for a 21st-century Jew to sympathize with the plight of the Samaritans that director Moshe Alafi portrays. And it is also easy to become an instant expert on this simultaneously iconic and unknown people.

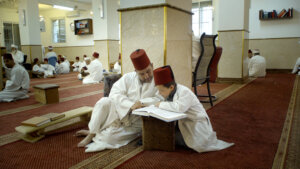

Alafi stresses the similarities between Jews and Samaritans in the opening sequence, where a narration tells a Jewish story of the Exodus familiar in scope, while the images paint a story that skews slightly from the Jewish one. The narration also includes important distinctions from the one told over Seders. Samaritans recognize Mount Gerizim as the holy mountain where Joshua built his altar when they ended their 40-year trek and also where Isaac was bound. They live in their holy land, split between two communities: one in Holon, the other in Nablus next to Mount Gerizim in Samaria. They trace their descent 127 generations in Israel from the original 12 Tribes.

Pigeonholed by Gospel stories and Christian tradition, it’s difficult to find any realistic representation of this people in Western civilization — and the recent Sylvester Stallone superhero film, “Samaritan,” about a disenchanted superpowered vigilante in hiding in Granite City, did not help matters. Even in conversations about Israel, they are routinely erased. No one ever consults them on the fate of the occupied territories of Judea (literally “the land of the Jews”) or Samaria (literally “the land of the Samaritans”).

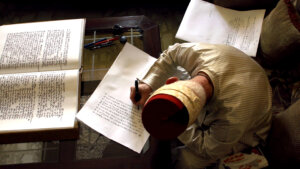

Yes, their head coverings are more like turbans and fezzes than kippot and yes, their Torah is written in a different ancient Semitic script from the Jewish Torah (the Samaritans think Ezra the Scribe changed the script in the 5th century B.C.E. while they preserved it), but Samaritans don’t seem, on a cultural level, to differ from America’s self-proclaimed normative Ashkenazi Jews more than Caucasian or Syrian Jewish communities. The distinctions are modern; the rabbis of the Mishnah were not willing to make a distinction between Samaritans and Jews.

To his credit, Alafi, an experienced Israeli filmmaker, interviews women and men of different generations, including those born in Nablus, Holon and Ukraine. And while he captures the distinctiveness of the community with his camera, there is no wholesale exoticization. The Samaritans don’t have a rabbinic tradition, so some customs, like daubing sheep’s blood on foreheads for Passover, still make biblical sense.

There are other unusual customs, like badal, which makes sure that brothers are wed before sisters are given away in marriage, and the ritual of m’samadeh, where the family and community celebrate, but also isolate, a menstruating woman. It’s not for the film to defend them, but they make sense in context that Alafi and his interviewees provide.

The film, mainly in Hebrew and aimed at an Israeli audience, encourages a natural kinship with these survivors from a biblical Middle East who cover their heads to pray, observe Shabbat, follow the Torah and actually slaughter the sheep that we are told to slaughter for Passover. But unlike the Jewish people who have, if not so many, at least several million people to play with, the Samaritan community consists of barely 850 people. “We’re a community that is becoming extinct,” says one of the many Samaritans interviewed.

The film addresses several challenges familiar to Jews thinking about preserving tiny communities. Knowledgeable elders like the chief priest, the last remaining scribe, the sole chazan, and the historian Benyamim “Benny” Tsedaka are dying off without obvious replacements. Tsedaka publishes the newsletter “A.B. The Samaritan News” in Ancient Hebrew, Modern Hebrew, Arabic and English, but there is scant news to cover.

New generations are less interested in tradition given the choices of modernity and, even if they were committed to in-marriage, there is an imbalance in the genders. Men — including even the son of the chazan who says that on a scale of 1-10, his love of Samaritanism is 11 – are having to look beyond the community for wives. Alafi presents and explains a millennia-old tradition at the same time as its current existential crisis.

In a filmed conversation, two of the elders discuss a rumor of “ten thousand Brazilians” who are interested in becoming Samaritan, but despite their speculations about how a mass influx of interested friends might work beside a tiny but committed community, nothing more is mentioned. One working solution to the crisis, though, is to bring brides in from Ukraine.

Though the subjects were all filmed before Russia invaded, these new Samaritans seem content. One, Ella Altif, is interviewed at length. Her long, straight platinum blonde hair is unlike all the other interviewees whose hair only approaches her hue with age. She discusses her friends “Shura, Tanya, Katya Gala, Yulia, Natasha, Vika and Nastya” and her own experience. She says she had no intention of leaving Ukraine to marry and certainly not into the Samaritans about whom she knew nothing. Now, however, she says she loves the traditions such as observing Shabbat. Though heavily accented, she is fluent in both Hebrew and Arabic, so she can talk to the Samaritan women from both Nablus and Holon who are the clients of her beauty business.

Though the film follows multiple stories, the heart of the film is the new couple, Shadi Ziv Altif and Natalie “Natasha” Podolyak. They are an everyperson couple. We see them in Kherson, Ukraine, where he has gone to woo her. He is endearingly forthright about his reasons for being there — “We go to the High Priest, the big Kohen, and he will make engagement for me and you.” He is earnest and sweet, perhaps “between 28 and 30,” the age at which one of the Samaritan women interviewed suggested that men ought to marry.

Natalie seems enigmatic, with hints of excitement, interest, worry. She is maybe 5 years younger than him. We see him pacing in Ben-Gurion airport, worried that she is not going to arrive. At the wedding, her reservations are clear, but she also responds to Altif’s enthusiasm and to the warmth of the welcome from the family and the wider community. Will she grow to love the community as Ella has? It seems possible.

Samaritans have a name from the Christian Gospels, and they are the people from Samaria, but they style themselves the Shamarim — the “guardians.” For millennia they have lived in the Holy Land and preserved their Torah — who is to say that they are not the true guardians of the Torah?

“The Samaritans: A Biblical People” has its world premiere at the 2022 Other Israel Film Festival on Nov. 8.