Can a bottle opener or perfume bottle pry open an entire Jewish history?

In Richard Rabinowitz’s memoir, unremarkable objects conjure up a story of identity and assimilation

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

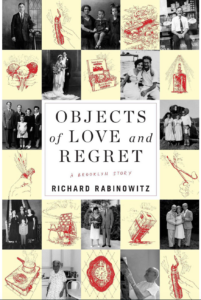

Objects of Love and Regret: A Brooklyn Story

By Richard Rabinowitz

Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 352 pages, $29.

“History catches up to us,” Richard Rabinowitz writes, “when we are least expecting it.”

In “Objects of Love and Regret,” Rabinowitz’s gently revealing memoir, one of this country’s leading museum makers reconsiders 20th-century American social history through the lens of one Jewish immigrant family and a handful of its possessions.

These homely objects — including a bottle opener, a perfume bottle, folding chairs and a television and stereo console — are Rabinowitz’s starting point, but they don’t straitjacket him. The president of the Brooklyn-based American History Workshop uses them like Proust’s famous madeleines, as a prod to memories and long-buried anecdotes. “Tell me the story of an acquisition you cherish,” he immodestly asserts, “and I will plumb the deepest struggles of your heart.”

That may be an unverifiable claim. But “Objects of Love and Regret” has other virtues. Employing his research skills as a Harvard-educated public historian, he describes the intersections of his family’s narrative with larger issues and trends: the balancing act between Jewish identity and assimilation, changing gender roles, racial and generational tensions, and the migration of urban dwellers to the suburbs and the Sun Belt.

The memoir genre involves its own tensions, between the specifics of individual lives and the quest for broader, more universal appeal. Some memoirs draw readers in through shock value alone. Rabinowitz relies instead on historical resonances and the elegance of his prose. “Remembered, recorded or not, forgotten, retrieved or not, we rent rooms in History’s house for a while, and then we are gone,” he writes.

This memoir is not pure elegy, though its inspiration was, in part, the death of Rabinowitz’s beloved mother, Sarah, at 99, and, even more so, his curiosity about her life.

Many of the book’s characters, among them a brutal paternal grandfather and a tempestuous father, are recognizably flawed. For the most part, though, in Rabinowitz’s sympathetic account, they manage the best they can, soldiering through social upheavals, employment crises and personal frustrations, sustained by familial and communal bonds.

Rabinowitz himself exemplifies the tensions and ambivalence he describes. He learns that “affection may be coupled with dependency and pain with liberation.” As a teenager, he longs to break free from the limitations of his lower-middle-class family and explore headier intellectual climes. As an adult, he appreciates his parents’ encouragement and love, qualities that helped enable his successful career.

The bottle opener about which Rabinowitz writes was a gift from his mother to her mother, Shenka Schwartz. The two had emigrated together in the 1920s from a Polish shtetl to New York, following Shenka’s husband, Dovid, after a six-year separation. Rabinowitz sees this modest utensil as a symbol of the powerful connection between the two women, arising from their temporary abandonment and shared domesticity.

Rabinowitz investigates the gadget’s commercial origins, but also its role in his family’s life. “That green-handled bottle opener magically pried open more than a beer bottle,” he writes. “It brought me into the tenement kitchen of my grandparents in the East New York section of Brooklyn in 1934,” a place where food symbolized both love and Jewish observance.

A perfume bottle — the scent was “Evening in Paris” — was the first gift that Dave Rabinowitz, the author’s father, gave his mother during their courtship. Rabinowitz surmises it might have been inspired by Hollywood images of glamour.

The perfume, never his mother’s favorite, serves as an introduction to his parents’ stormy but enduring 72-year marriage. His father’s abusive upbringing, uneven success as a provider during the Great Depression, tax problems and crushing business competition sometimes triggered rage. His moods would shift “from celebratory exuberance, then to explosive anger, and then again to warm possessiveness,” his son writes. Rabinowitz’s mother rode out these squalls. “Her cardinal principle was a deep devotion to the sanctification of the everyday,” Rabinowitz writes.

The family’s aluminum and plastic folding chairs conjure stoop sitting and, later, beach and park excursions, even as their East New York neighborhood is transformed by Black migration and blockbusting. A Magnavox television and stereo console attests to the changing nature of leisure in mid-20th-century America. It’s supposed to represent togetherness, but family tastes diverge. A rebellious Rabinowitz disdains the era’s variety shows and sitcoms and gravitates instead to classical music.

While absorbing his family’s anxieties, Rabinowitz also appreciates its gifts and the good fortune of his birth. “Boys with promise were the choice crop of the Jewish communal enterprise,” he writes. He knows that his older sister, Beverly, faced a far more tortuous route both personally and professionally. As the repository of considerable family lore, Beverly becomes one of his principal sources, and Rabinowitz dedicates the book to her.

One of the memoir’s ironies is that this is not, in the end, a family much defined by its material possessions. Rabinowitz’s ancestors transported few heirlooms with them from Europe. And they preserved only a few of their U.S. acquisitions, shedding objects each time they moved — ultimately, in his parents’ case, to a Century Village retirement community in Deerfield Beach, Florida.

Perhaps that renders the surviving objects — or the mere recollection of those objects — all the more potent. Rabinowitz is artful in drawing out the memories and meanings they elicit. Perhaps even more valuable is his encouragement to the rest of us to examine our material world, and to follow his lead.

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly referred to the bottle opener as a can opener.