How the sesame seed became the most Jewish of all ingredients

Plus, a recipe for the best Chinese sesame noodles you’ve ever tasted (no peanut butter required)

A favorite Jewish ingredient meets a classic Chinese recipe. Photo by Liza Schoenfein

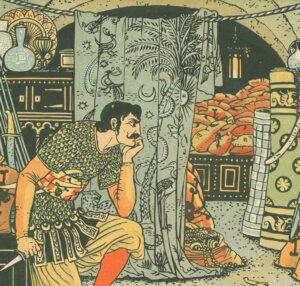

When the poor Persian woodcutter Ali Baba overheard the leader of a band of thieves stand before a cave and say “open, sesame,” it changed his life forever. Those magic words unlocked unimaginable prosperity.

But why “open sesame” of all phrases? One theory holds that the word sesame — sesamum in Latin — sounds a lot like the Hebrew word sisma (or seesma), which loosely translates to “password.”

Another theory is that the opening of the cave in this tale from The Arabian Nights represents the dramatic splitting open of the tubular sesame seed pod — the fruit of the plant — each of which contains 75 to 100 seeds. In nature, the pods burst open when ripe, scattering the teardrop-shaped seeds, a most valuable bounty, upon the ground. In this way, “open sesame” is very literally a means of gaining access to hidden treasures.

Like the story of Ali Baba, the tale of the sesame seed itself is a rags-to-riches story. What is it about this lowly seed that makes it one of the most iconic ingredients in all of Jewish culinary history?

Jewish cuisine encompasses not only tahini — arguably the juice that fuels Israelis, who reportedly consume 50,000 tons of sesame seeds a year, mostly in the form of tahini — but also sesame candies, halva, sesame bagels and of course Chinese sesame noodles.

Jews have been consuming sesame seeds and pressing them into oil for millennia. “The Mishnah includes shemen shumshum among the oils suitable for kindling the Sabbath lights,” wrote culinary historian Gil Marks in his indispensable volume, The History of Jewish Food. “The Talmud explained, ‘What would the Babylonians do [if only olive oil was permitted for the Sabbath lights] who have nothing but sesame oil?’”

“The Bene Israel of Mumbai were called Shanwar Teli (Saturday oilmen) by their non-Jewish neighbors as they primarily made their livelihoods preparing and selling sesame oil, refusing to work on the Sabbath,” Marks continued.

From oil it’s just a short hop to tahini, which was the byproduct when sesame seeds were pressed into oil. Tahini, Marks points out, comes from the Arabic word for “ground,” which is tahn.

A remembrance of sesame seeds past

In my childhood, sesame seeds were ubiquitous, though I didn’t think about them too much. Growing up in Manhattan in the 1970s, my earliest memory of sesame seeds had nothing to do with tahini, but with those little rectangular candies wrapped in cellophane — sesame seeds and honey compressed into a sweet and nutty treat about the size of a classic Lego brick.

I grew up in a household devoid of junk food, sugar cereal and candy. These little confections sometimes made it past the prohibition because, I imagine, our mother picked them up at a health food store and they were, after all, made of seeds. (We also managed to slip a sugar cereal called King Vitamin by her for a while. Clever cereal company; clever children — but neither as clever as Sandy Schoenfein, who figured out this ruse all too soon, sending my sister and me back to the health-nut-approved land of Grape Nuts and Shredded Wheat.)

There were always freshly cut carrots and celery waiting for us when we got home from school, but alas no hummus (it had calories), though there was a can of Joyva tahini on a shelf in the back of the cabinet. I’m not sure my mother ever used it, but there it sat, a harbinger of happy tahini-doused culinary experiences to come.

Another early childhood memory is visiting my grandparents in Massachusetts and my grandfather unwrapping a block of something beige and streaked with brown — certainly not the most exciting or appetizing of sights. That is until he took a little knife and sliced off an uneven chunk of the stuff, handing it to me with a look of joyful expectation. I tasted it, and the intensely rich flavor and dry, slivery, slightly oily (and surprisingly pleasing) texture just blew me away. To this day, halva makes me think of my smiling Papa Max, his eyes twinkling above the narrow reading glasses forever perched on the tip of his nose.

Even in my highly health- and weight-conscious home, there were sesame bagels on Sunday mornings and Chinese sesame noodles on Sunday nights, the latter probably made with peanut butter in lieu of (or mixed in with) sesame paste.

This peanut butter issue always bothered me a little. Did restaurants assume that American palates craved the familiar? Or was peanut butter just that much more accessible? (Certainly yes, and probably yes.) In any case, I decided to create an authentic-tasting, entirely sesame-based recipe for Chinese sesame noodles — and by that I mean a dish that resembled the familiar flavor of so many Sunday night dinners, not the flavors of China, where this would be entirely unfamiliar. The resulting noodles are a sublime riff on the original and a paean to the mighty, magical sesame seed.

How to make the best cold Chinese sesame noodles — hold the peanut butter

While most recipes for Chinese Sesame Noodles — including those served in American Chinese restaurants — call for peanut butter, this one stays true to its name, employing four different forms of sesame: sesame oil, Chinese sesame paste, tahini, and sesame seeds. The recipe yields about one cup of sauce — just right for swathing a pound of noodles. The sauce can be made in advance and stored in the refrigerator for a few days before using — just be sure to bring it to room temperature before tossing with noodles.

Sesame noodles

1 pound fresh or frozen Chinese egg noodles or dried spaghetti

3 tablespoons soy sauce

1 tablespoon toasted sesame oil

1 tablespoon unseasoned rice vinegar

3 tablespoons Chinese sesame paste

¼ cup tahini

1 tablespoon honey

1 tablespoon finely minced or grated ginger

2 small cloves of garlic, finely minced or grated

1 teaspoon chile oil or chile crisp (such as Fly By Jin or Momofuku)

Ice water

3–4 scallions, white and light green parts cut into 2-inch pieces then slivered lengthwise

2 tablespoons lightly toasted sesame seeds

- Cook noodles in a large pot of boiling water according to package directions but minus a minute or two. (Noodles should be al dente.) Drain, and rinse with cold water.

- Meanwhile, combine soy, sesame oil, rice vinegar, sesame paste, tahini, honey, ginger, garlic, and chili oil/crisp in a medium bowl and whisk until incorporated. The mixture will be very thick. Add about a tablespoon of ice water and whisk, adding a little more if needed, until the mixture lightens in color and becomes smooth but not liquid.

- Taste the mixture and adjust as desired, making it more salty with additional soy, sweeter with additional honey, or spicier with more chile oil/crisp.

- Add the noodles to the bowl and stir until they’re evenly coated with the sauce. Top with scallions and sesame seeds.