At 89, Cormac McCarthy has created his first Jewish characters — not that it matters

In ‘The Passenger’ and ‘Stella Maris,’ we meet Bobby and Alicia Western, whose exploits are more compelling than their surname

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The Passenger

By Cormac McCarthy

Knopf, 400 pages, $30

Stella Maris

By Cormac McCarthy

Knopf, 208 pages, $19.99

Cynthia Ozick was in her 90s when she wrote Antiquities, one of the essential American novels of our young decade. Don DeLillo was deep into his 80s when he finished The Silence, a barmy hybrid of bang and whimper. Thomas Pynchon, 85, hasn’t published anything in close to a decade but recently sold his literary archive; the possibility of one last novel looms gigantically over Anglophone letters like a rocket about to hit its target. Joyce Carol Oates, 84, has published 14 books in the last five years, saving whatever eloquence she has left over for Twitter.

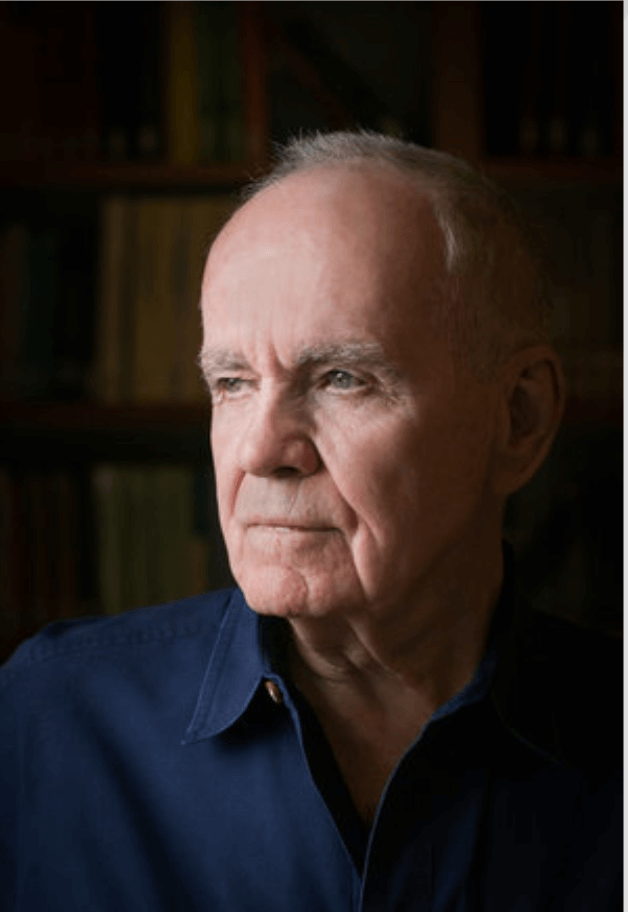

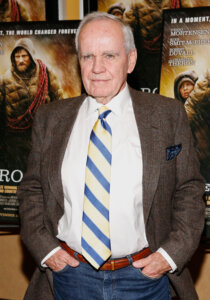

Of the living American novelists old enough to remember World War II, Cormac McCarthy is among the bestselling (with a little help from Oprah, The Road moved 1.4 million copies), the most prize-laden (Pulitzer, MacArthur, etc.), and the most polarizing. Until recently, his writing was difficult to sort-of like or dislike: These were novels you either snorted at or bowed before, and as such, his success wasn’t a slow climb but an overnight upsurge.

In 1992, he was nearly 60 and the author of five dense, dark, Faulknerian novels, none of which had sold more than a couple thousand copies. Then came All the Pretty Horses, a National Book Award, and rushed reassessments of those early works. Blood Meridian — his scalp-ripping, skull-crunching, blood-spewing Western, first published in 1985 — zipped to the top of lists of the best postwar American fiction, and by the late 2000s, if you were a bookish teenage boy looking to check some canonical titles off your list, McCarthy’s genius seemed as elemental as the tides. Now, at the age of 89, he has published two interlinked novels.

The Passenger and Stella Maris are, in striking contrast with McCarthy’s previous work, hard books to love or loathe unconditionally; they are uneven as a mountain range. They polarize the individual reader, often within the span of a single paragraph. From page 62 of my edition of The Passenger: “He lit the cigarillo for her and she leaned back and crossed her rather remarkable legs with an audible rustle and blew smoke toward the stamped tin ceiling with a sensuous and studied ease. Thank you, Darling, she said. At nearby tables diners of both sexes had stopped eating altogether. Wives and girlfriends sat smoldering. Western studied her pretty closely.”

What should you do with this? Roll your eyes at the freshman clumsiness of “pretty closely,” or relish the expertly understated comedy of restaurant patrons smoldering at the sight of a cigarillo-smoker? Puzzle over that “audible rustle” (if a lady crosses her legs and nobody hears, does it make a sound?) or gape at the way McCarthy makes his sentence’s studied, sibilant alliteration mirror the content, so that to read is to see through the woman’s performance and be seduced at the same time?

It’s all like this, almost 600 pages put together — not just the prose but the characters and plot, too. “Western,” in the passage I just quoted, refers to Bobby Western, one of these books’ two protagonists — the other is his younger sister Alicia — and possibly the most nudgingly named character in American literature since Coleman Silk from The Human Stain.

Bobby and Alicia are Jewish, gorgeous, brilliant, madly in love with each other, and equal parts indecipherable and unbelievable. Alicia, a mathematical prodigy and the owner of a $230,000 violin, suffers from schizophrenia and spends much of both novels in a mental hospital, talking to a doctor named Cohen or, when she’s alone, to a flipper-limbed hallucination called the Thalidomide Kid; as The Passenger begins, it is 1972 and she has committed suicide. Bobby, a salvage diver, is as mobile as his sister is confined — his side-hustle as a race car driver takes him all over Europe — but he passes most of his time in New Orleans.

Like Faulkner, his idol and (along with Melville) principal influence, McCarthy loves movies and learned a lot from them (Apocalypse Now casts as long a shadow over Blood Meridian as Heart of Darkness). He tried to sell No Country for Old Men as a screenplay before publishing it as a novel, went on to write a delightfully bonkers screenplay for Ridley Scott’s The Counselor, and stuffs his books with fistfuls of hard, spiky, post-Production Code violence.

The Passenger owes something to the arty existentialist thrillers of the ’60s and ’70s, with their one-two punches of languor and danger — Le Samourai, maybe, or for that matter Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger. Early in the novel, Bobby Western discovers a sunken jet from which a body has gone missing and — not unlike Jack Nicholson in the Antonioni film — spends the rest of the novel being menaced by government agents of some kind or other. (Stella Maris is a shorter, less cinematic, and, it must be said, worse book, mostly consisting of conversations between Alicia and Dr. Cohen that seem suspiciously like outtakes from its longer companion.)

Like Antonioni, McCarthy at first suggests the answers are on their way and then delays indefinitely. Instead of sharpening into a fine point, the mystery of who was in that jet simply melts into air, leaving its peculiar flavor on every page. Could the accident possibly be connected to Alicia and Bobby’s father, one of the architects of the atomic bomb? Could it have something to do with the Kennedy assassination, which Bobby discusses at great length with an old friend? What’s with the violin? Does it matter, even thematically, that the Westerns are Jewish? One might as well ask after Schrödinger’s cat.

In lieu of answers, McCarthy provides images whose beauty, vividness and occasional humor somehow transcend the mystery by distilling it; I’m thinking in particular of a long, dreamy scene in which Bobby, grieving for his dead sister, meets the Thalidomide Kid, flippers and all, a hallucination that has unaccountably survived its hallucinator.

It’s a magnificently aimless piece of writing and easily one of the best parts of the new novels, gushing with inventive description (of a dying campfire: “bits of fire hobbled away down the beach into the darkness”), epigrammatic weirdness (“You share half your genes with a cantaloupe”), and yes, humor (“The Kid sat and studied his nonexistent nails”).

The Kid invites Bobby to ask him anything and then refuses, rejects, or revises every question he’s asked (notably, Bobby doesn’t ask, “Did you know we were in love?”). “In the end,” he concludes, “you really can’t know. You can’t get a hold of the world. You can only draw a picture. Whether it’s a bull on the wall of a cave or a partial differential equation it’s all the same thing.” Reality can only be approximated with human ingenuity, never fully understood: not with science, not with mathematics, not with art, not even with language — perhaps with language least of all.

These sentiments appear in The Passenger and Stella Maris too frequently to be accidental, and they’re probably the best explanation for why McCarthy sets up his thriller plot only to neglect it. Accuse me of flailing around in the dark for a skeleton key if you like, but it strikes me that these novels are, at heart, about the failure of language to keep pace with the unconscious mind: people’s failure to express their feelings, to ask the right questions, to give the best advice, to talk themselves clean or sane or happy. The unconscious mind knows all, but the unconscious mind is a poor communicator (that, or the conscious mind is a lousy understander), and so evil remains unknowable and passenger stays missing.

To be evil, perhaps, is to seek to tame the world with language and perfect understanding — a possibility McCarthy raised before with Judge Holden, the villain of Blood Meridian who declares, “Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.” (Speaking of which, the connection between Blood Meridian’s The Kid and The Passenger’s Thalidomide Kid can’t be accidental, either.)

Am I letting McCarthy off the hook too easily? There aren’t many novels I’d recommend that feature dozens of pages of desultory conversation or make little effort to resolve their plots, and yet here I am, recommending The Passenger to anyone who’s still reading (Stella Maris you can skip). John Jeremiah Sullivan, reviewing the novel in The New York Times, said he felt like he was enabling an abuser when he defended McCarthy from the charge of tediousness.

I get where he’s coming from, because I used to be that bookish teenager checking Blood Meridian off my list, and when a writer does for you what McCarthy did for me back in the day, there is no “pretty closely” or fizzling plotline you won’t forgive. But the critic Michael Gorra, writing about a different incest novel, The Sound and the Fury, suggested that Faulkner’s writing was intentionally incoherent in places in order to mirror the failure of escaping Confederate history, and I’d venture a similar claim about The Passenger: Its roughness is a part of its charisma, its glory and — dare I say? — its portrait of contemporary life. Long after hundreds of more polished novels have evaporated from my memory, I have a feeling I’ll still be shuddering at the Kid’s flippers.