For a Jewish family in Ukraine, a wrenching choice between Israel and the U.S.

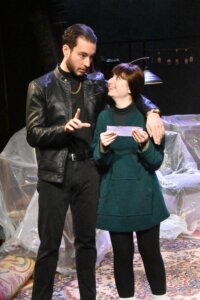

In Stephanie Satie’s ‘Last Parade,’ a domestic argument reflects global conflicts

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Stephanie Satie sets The Last Parade in 1991 Kyiv, in a fracturing Soviet Union. A family of Russian-speaking Ukrainian Jews, eager for a life both freer and more prosperous, has applied to immigrate to Israel and the United States. As family members debate their options, their divides reflect both the splintering Soviet empire and the dilemmas faced by immigrants everywhere.

Philadelphia’s InterAct Theatre Company, now marking its 35th anniversary season, specializes in new and contemporary plays with political, social or cultural relevance. Its solid world-premiere production of Satie’s two-act drama is an authentic-seeming snapshot of a particular time and place. But it also gestures back to the bureaucratic quagmire confronting European Jews trying to flee Nazism in the 1930s and ’40s, and forward to the newly contentious relationship between Ukraine and Russia.

In early 1991, Ukraine hovered on the brink of independence. But political control still rested, however tenuously, with Moscow; the U.S. government was imposing its own immigration hurdles and safeguards; and Jewish emigration from the soon-to-be-former Soviet Union, though possible, was not yet as easy as it would become. This last factor becomes the play’s ironic underpinning.

As the action begins, the Minkovski/Kaminski family has received an invitation from Israel to settle there. Mother Zoya (Leah Walton), a biologist who checks farm produce for radiation from Chernobyl and bizarrely collects rugs and chairs for the imminent move, wants to accept. Who knows, after all, what will happen with the U.S. application, and when the door to departure might close?

The main impediment seems to be teenage daughter Anya (Ava Weintzweig), whose earlier visit to her aunt in California has left her enraptured with American material abundance and culture. Whether the United States, with its own embattled democracy, can fulfill its promise to future immigrants is one of the questions raised by the play.

Anya, an aspiring fashion designer, has no doubts; for her, it’s America or bust. She is inexplicably certain that a lottery ticket for a green card, supplied by her loving gangster brother Borya (Adam Howard), will ensure the family’s immigration prospects. She wants the family to await the lottery result, even if it jeopardizes their Israel option. And she’s not above deception to get her way.

She is not the only one. The heaviest anchor to the Soviet past may be father Leon (Anthony Lawton, in a nuanced and heartbreaking performance). “I want you to be brave. Not to be like some old horse that can’t wait to get back to the stable,” Zoya tells her husband. Even after being laid off from his longtime scientific post, Leon is reluctant to leave Ukraine. He totes around a heavy English-Russian dictionary, another symbol of transition. But he lacks the energy to start a new life, more so even than Zoya’s father Yasha (Tim Moyer), who is still capable of excitement about a Chagall exhibition in Moscow.

As directed by Seth Rozin, InterAct’s producing artistic director, The Last Parade has heart and zest. Satie can be very funny on the headaches of Soviet life: a refrigerator so creaky that it needs to be taped shut, the dearth of modern communication technology, the omnipresence of post-Chernobyl radiation, incessant queues, and food shortages both caused and alleviated by corruption. But Rozin’s actors too often seem to be rushing through their laugh lines.

One exception is Howard’s Borya, the family fixer, who doubles as the play’s narrator. Telling the story in flashback, he delivers his monologues with dry humor and a convincing Russian accent. (When the characters are supposed to be speaking Russian, their accents, sensibly enough, disappear.)

In other respects, Satie’s script seems a draft away from completion. It remains unduly repetitive, its plot more convoluted than necessary. When Walton’s domineering Zoya and Weintzweig’s self-centered Anya spar in the first act, it is hard to decide which is more annoying. Neither woman is good at listening, and the argument grows tiresome.

Satie’s introduction of her metaphorical throughline also seems clunkier than it should be. The title refers to the endless onslaught of parades sponsored by the Soviet Union for its array of holidays. The metaphor stretches to cover both the fateful procession to Babyn Yar and long Soviet lines to secure food. To Leon, the march to exit the country seems like just another parade, potentially tragic or meaningless.

Under Perestroika, “everything in our country was under reconstruction, meaning that everything was closed. Except the door out,” Borya explains in his opening monologue. In The Last Parade, the costs of walking through that portal are steep, and not everyone can make the journey.

The Last Parade plays at InterAct Theatre in Philadelphia through Feb. 19.