Was a Jewish soldier the only man to get out of the Alamo alive?

Louis Moses Rose: Coward or survivor? Fact or fiction? Jewish … or not?

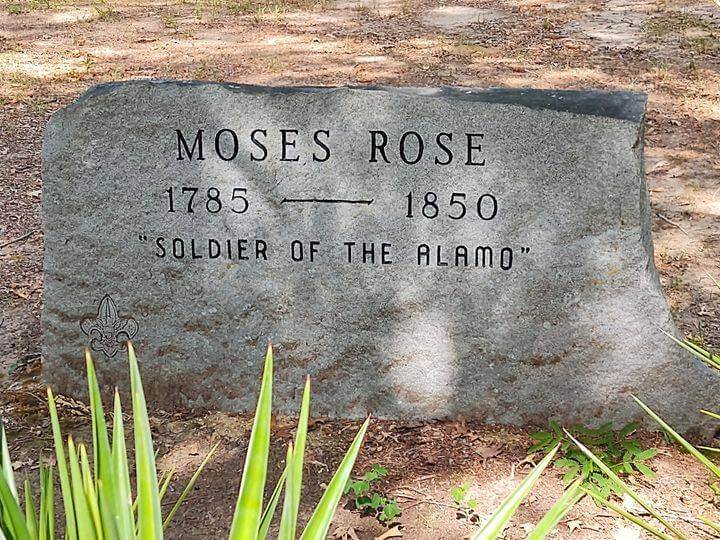

A gravestone in a Louisiana cemetery for Louis Moses Rose, said to be the sole survivor of the Alamo. Photo by O. Thomas Welch

Remember the Alamo? The storied battle took place during the Texas war for independence from Mexico. Frontiersman Davy Crockett was among 200 men holed up in an old Spanish mission used as a fort during a 13-day siege by thousands of Mexican soldiers. It ended with a battle on March 6, 1836, that left Crockett and all of his comrades dead.

But one man got out alive — or so they say. His name was Louis Moses Rose, and according to some accounts, he was Jewish. But was he? And if he escaped the fate that befell the others, does that make him a survivor — or a coward?

A French soldier in the Napoleonic wars

This much is undisputed: A man named Louis Rose was born in 1785 in La Férée, in the Ardennes, “a region of France with a sizable Jewish population,” Forward contributor Steven Kellman wrote in a 1982 article for the Alamo Lore and Myth Organization newsletter.

As a soldier in the Napoleonic wars in the early 1800s, Rose served in Naples, Portugal, Spain and possibly Russia. He earned a French Legion of Honor award, and his enlistment coincided with a period when “Jews were first being conscripted” into the French Army, Kellman, a professor of comparative literature at the University of Texas, wrote.

In 1827, a man with the same name turned up as a sawmill worker in Nacogdoches, Texas. The town had a community of Jewish immigrants, and it had been under French control until the 1760s, so it was a logical place for a French Jew to settle.

The Texas State Historical Association says that Louis Rose of Nacogdoches took part in three armed conflicts between Anglo settlers and Mexican authorities between 1826 and 1835. Two of those conflicts took place in the Nacogdoches area. The third took place in San Antonio not long before the Alamo.

Crossing the line

Here’s where things get murky. In 1873, more than 20 years after Rose’s death, a letter was published in the Texas Almanac from a man named William Physick Zuber, recounting a story Zuber’s parents had told him. The story goes that Rose showed up at their farm in March 1836 with bloodstained clothes and infected wounds, saying he’d escaped from a battle at the Alamo in which everyone else died.

Rose said the Alamo’s commander, William Barret Travis, had told the fort’s defenders they were doomed. Travis then drew a line on the ground with his sword, and asked everyone who was prepared to stay and die with him to cross the line.

Everyone crossed except for Rose. “You seem not to be willing to die with us, Rose,” the legendary frontiersman Jim Bowie supposedly said.

“No, I am not prepared to die, and shall not do so if I can avoid it,” Rose responded.

Kellman, in a phone interview last week, considered Rose’s reasoning. “He was about twice the age of all the other defenders. He had fought in Napoleonic wars in Italy and Spain and France with distinction and earned several medals. He must have thought to himself, ‘I survived all of that. Why should I die here in this little hole in the wall?’”

According to Zuber, Rose then scaled a wall and somehow managed to get through the thousands of Mexican soldiers outside the fort. “His swarthy complexion and black hair and the fact that he was more fluent in Spanish than English contributed to his success in evading capture by Mexican forces,” Kellman wrote.

Rose then made his way to Zuber’s parents’ farm to tell his story. Zuber’s letter was accompanied by a note from his elderly mother attesting to its veracity.

The tale of Travis literally drawing a line in the sand fed the notion that the Alamo defenders were not a hapless bunch with no idea what they were in for. Instead, this story portrayed them as courageously choosing to stay, knowing they would die — all except for Rose, that is.

Today, many scholars view the line in the sand story as lore, not fact. But it captured the public’s imagination and was repeated in subsequent accounts, including an 1888 book, A New History of Texas, that was a standard school text for years.

‘I wasn’t ready to die’

In 1939, a court reporter named Robert Blake unearthed testimony Rose gave in Nacogdoches in the 1840s on behalf of families seeking to prove their menfolk had died at the Alamo. The testimony helped them qualify for land grants given to veterans’ heirs.

Rose apparently had no trouble asserting that he alone survived. “By God,” he said more than once, “I wasn’t ready to die.”

“Yet there was no evidence in 1939, and still none today, that he fought at the Alamo, much less that he watched Travis draw any line in its sand,” according to a 2021 book called Forget the Alamo, by Bryan Burroughs, Chris Tomlinson and Jason Stanford, that has challenged many assumptions about the battle. “Despite all the times he claimed to have been there, there is no other record, nor even a secondhand account that he ever told the story the Zubers attributed to him.”

But was he Jewish?

You’d think Rose’s nickname, Moses, proved his Jewishness. Alas, no: They called him Moses for his long beard, and because, at age 51, he was so much older than others at the Alamo.

Kellman said Rose had another less flattering nickname during his final years in Nacogdoches, when he was sometimes called Luesa, “the Spanish feminine form of Louis and a way of taunting him for his presumed cowardice.”

Chris Tomlinson, one of the authors of Forget the Alamo, said in a phone interview that he thinks Rose was Jewish, but can’t be sure.

“It’s so hard to separate the Louis Rose we found in the records in Nacogdoches with the Moses Rose who’s almost a complete invention, who was supposedly at the Alamo,” he said. “Moses Rose, that character in the myth of the line in the sand, is a French Jew who fought in the Napoleonic Wars, and the implication is that he was a coward. He’s the only one who refused to cross the line. And of course that’s loaded with antisemitism. Was he turned into a Jew so that makes him even more evil in the story? Possibly.”

Kellman agreed that making Rose out to be Jewish echoes “the scapegoating of Jews throughout the centuries.” It also contributes to “the myth of the wandering Jew,” he wrote, casting Rose as “a pathetic alien without binding ties to any person or place.”

Rose never married but he had a nephew named Isaac. Kellman tracked down one of Isaac’s descendants to ask if they were Jewish but was told the family had nothing more than a rumor of Jewish heritage from generations back.

Rose died in 1850 in Louisiana at the age of 65. A newish-looking gravestone in a cemetery in Funston, Louisiana, bears his name and the words “SOLDIER OF THE ALAMO” but no hint of his religion.

Moses Rose’s Hideout

There’s a 21st-century twist to Rose’s story. When Vincent Cantu opened a bar 12 years ago just steps from the Alamo, he created a speakeasy-style atmosphere with a hidden entrance. “I thought, who can I tie that into, being so close to the Alamo, that would need a hideout?” Cantu said in a phone interview. And so the bar was called Moses Rose’s Hideout.

But now Moses Rose’s Hideout is under siege. A $300 million project dubbed the Alamo Plan calls for construction of a “museum and visitor center to create a unique and educational experience” for visitors to the Alamo. To make way for construction, Moses Rose’s Hideout will have to go.

In January, the San Antonio City Council authorized the use of eminent domain to acquire the property. “‘Coward of the Alamo’ may need new hideout,’” was the headline in the San Antonio Express-News.

Cantu did not appreciate the comparison. “In the paper, I’ve been called dishonorable. I was called a person with bad faith, someone who wouldn’t come to the table, that I was standing in the way of the historic rebuilding of the Alamo complex,” he said. “I own a private property coveted by them. I’ve never been treated even with a modicum of respect. I’ve told them I would sell it to them. At the end of the day it would be great to sit down with these people and not have a loaded gun pointed at my head, but as a free market capitalist instead say, ‘let’s make a deal.’”

So far negotiations have been unsuccessful, but Kate Rogers, executive director of the Alamo Trust, said in a statement: “We are optimistic that we will reach an agreement on a reasonable purchase price.”

Some things are ‘unknowable’

The Alamo Historical Society Facebook group has 6,000 members. Several were quick to defend Rose in response to a post seeking comments for this story.

“As a veteran of wars on two continents, there’s no shame in Moses Rose leaving the Alamo,“ wrote one group member.

“Moses Rose was French and had no dog in the fight,” wrote another, adding: “So many tall tales that it is hard to separate the truth from the story.”

Kellman, in his article, conceded that much about Rose is “unknowable.” But he said the Alamo “has been preserved, physically and psychically, as a monument to a golden age when men were presumably capable of united heroic action.” Rose’s story, however, is the footnote reminding us that everyone has a mind of their own, and that “not every heart within the courtyard of a beleaguered Texas mission beat in fervent unison.”

Correction: Corrects year of Rose’s death to 1850 and deletes erroneous reference to French Alsace region.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.