A nuanced and disquieting vision of Europe after the Holocaust

Thirty years ago, photographer Jill Freedman sought to document sites of destruction and the resurgence of Jewish life

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Thirty years ago, on the 50th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, photographer Jill Freedman traveled to Poland to document sites of destruction and the resurgence of Jewish life after the Holocaust in Poland and beyond.

Best known as a self-taught documentary photographer in the spirit of Dorothea Lange, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Weegee, Freedman launched her career in 1968 in the wake of Martin Luther King’s assassination when she joined the Poor People’s Campaign march to Washington, D.C., and photographed the encampment, called Resurrection City, set up by the demonstrators on the National Mall.

These images, printed in Life magazine, were her first to be published. Freedman went on to publish seven books of photography, which explore such topics as New York City police officers and firefighters putting out the much publicized flames (literal and metaphorical) in Harlem and the South Bronx during the mid-1970s.

Missing Generations: Photographs by Jill Freedman, currently on view at the Derfner Judaica Museum and Art Collection in Riverdale, features 36 of her most vivid and evocative black and white shots from her trip to Poland. The nuanced and disquieting pictures have never before been seen in public.

A survivor at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum holds his arm aloft displaying his tattooed numbers. He is asking an onsite administrator for information about the fate of family members also imprisoned at the concentration camp. Like many of the photographs this one is simultaneously matter-of-fact and shocking.

Freedman’s Jewish roots were always present, informing her work, said chief curator and museum director Dr. Susan Chevlowe, who previously served as curator at the Jewish Museum and whose area of expertise is photography, the Holocaust and visual representation.

Freedman, who was born in 1939 — and died in 2019 after a long bout with cancer — grew up in a culturally Jewish home and came of age in Squirrel Hill, Pa. She first became interested in photography as a teenager after viewing the horrifying yet visually compelling photographs of the Holocaust published in Life magazine. They spoke to her aesthetically while evoking intense outrage. Following her graduation from the University of Pittsburgh, she lived in and worked at an Israeli kibbutz.

In the early 90s, wartime atrocities in Bosnia and Rwanda, which coincided with a rise in global antisemitism and Holocaust denial, led Freedman to journey to Poland on the 50th anniversary of the Warsaw uprising. Her ambition, according to Chevlowe, was “to capture the milestone events that took place beginning with commemorations in 1993, including the return of many survivors for observances in Warsaw and at Auschwitz.”

“When Freedman went to Poland in April 1993, she wrote that she made the journey as a pilgrimage ‘to mourn the dead, to honor them,’ along with the survivors, their children, old soldiers and witnesses,” Chevlowe said. “She returned to many of these sites the following year to expand her project to meet survivors and document their gatherings, their faces, their stories, their interactions.”

Freedman also photographed residents of a Jewish nursing home in Szeged, Hungary; a summer camp in Szarvas, Hungary, where Jewish children from Eastern Europe learned about traditions that had been nearly annihilated; and she made portraits of survivors celebrating events or reflecting on memories in South Beach Florida.

“I think the work is very timely, both because of the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and because of the rise in and awareness of antisemitism today and the connection to social justice,” Chevlowe said. “Jill made a connection between bringing visibility to the history of the Holocaust and the persecution of groups, individuals, and the broader struggle for justice for all people. She felt deeply that the world had not done enough to save the Jews and that it could happen again. Injustice was all around her during her lifetime, and she picked up a camera to fight it.”

The Freedman family welcomed Chevlowe and encouraged her to select shots from archival materials, including a mock-up for a book of Holocaust memorial photos, which Freedman never had a chance to complete or see published.

Chevlowe used the mock-up as a loose guide in setting up the exhibit. The result is a chronological journey of pictures that traces Freedman’s trip from Warsaw to various cemeteries and concentration camps. The pictures are thematically connected and sometimes underscore brutal juxtapositions. One shot depicts three Polish teenagers cleaning an old Jewish grave site while noting, the caption explains, that Jews are exceedingly wealthy, but keep their money hidden.

The next photo, set in a Jewish cemetery, portrays an elderly Jewish woman extending a bag of dirt to a young boy to scatter onto a casket below the freshly dug hole in the ground. The authenticity of emotion and heartfelt ritual seen here casts an even darker shadow on the three teens, who continue to voice antisemitic tropes.

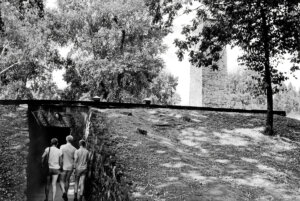

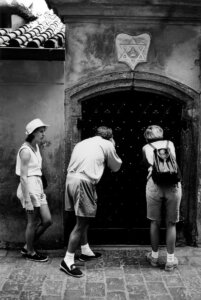

The detailed conversations Freedman had with her subjects, which inform the captions, are seminal to her aesthetic. Indeed, the presence of people — survivors, tourists, Jews and Gentiles — at the various sites, and reacting to those sites are a defining hallmark of her work.

“She likes closeups and the photographs are intimately focused,” said Chevlowe as she gestured to a photograph in the exhibit. “Instead of a wide shot featuring a long stretch of overgrown tracks leading to a concentration camp, she will focus her lens on a note that someone wrote and placed on a smaller piece of track. The handwritten note says ‘To the memory of six million killed in the Holocaust and members of my family that I never knew.’”

From a compositional, formal standpoint her work embodies contrasts as well, Chevlowe explained: “One shot is set indoors, the next is outdoors. One is industrial, the next is set in nature, one shot is horizontal while the one alongside it is vertical.”

Freedman is among several notable photographers who photographed Holocaust memorials, scenes of destruction and Jewish rebirth in those cities, most decimated by the Holocaust. But, what makes Freedman’s work singular, said James E. Young, an emeritus professor and founder of the Institute for Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies at UMass Amherst, is the presence of people responding to these sites with their own recollections.

“Whatever memory occurred here took place in the visceral exchange between visitors and these sites, animating these otherwise silent, even amnesiac sites with their own memory,” Young told me.

Chevlowe, who worked alongside Young at the Jewish Museum, said, “I think what unified the photographers is that they all witnessed a gaping absence, an event that was beyond representation, but that as photographers their work provided some kind of entry point for others to begin to learn, connect, understand, and, behind the camera, to also find their own personal connections to the tragedy,”

Arguably, in lesser hands these photographs might run the risk of trivialization, exploitation and even Holocaust fetishism. But Freedman’s work spawns empathy, Chevlowe said.

Chevlowe told me her ambition is for as many visitors as possible, most pointedly youngsters from a range of cultural economic backgrounds, to view these pictures. “I take the position of the United States Holocaust Museum. I believe photographs like these — portraying a far removed genocide — can arouse empathy and have an impact,” she said.

Missing Generations: Photographs by Jill Freedman, runs through July 16 at The Derfner Judaica Museum + Art Collection in Riverdale.